From the July 1990 issue of the late, great Recording Engineer/Producer (RE/P) magazine, technical editor Mike Joseph interviews a studio owner competing against the big boys and flying under the radar.

In an effort to promote balanced journalism, RE/P has endeavored to present both sides of the ongoing issues surrounding commercially directed, so-called home project studios.

More of a strong concern in the U.S. major coastal markets, the ethical and legal aspects of low-overhead, for-profit, residentially based audio production facilities need to be discussed, understood, and come to terms with, whatever one’s personal or professional feelings.

Residential studios that sell time won’t go away, and the proliferation of less-expensive, higher-power hardware merely mitigates the ease with which high-quality work can be accomplished.

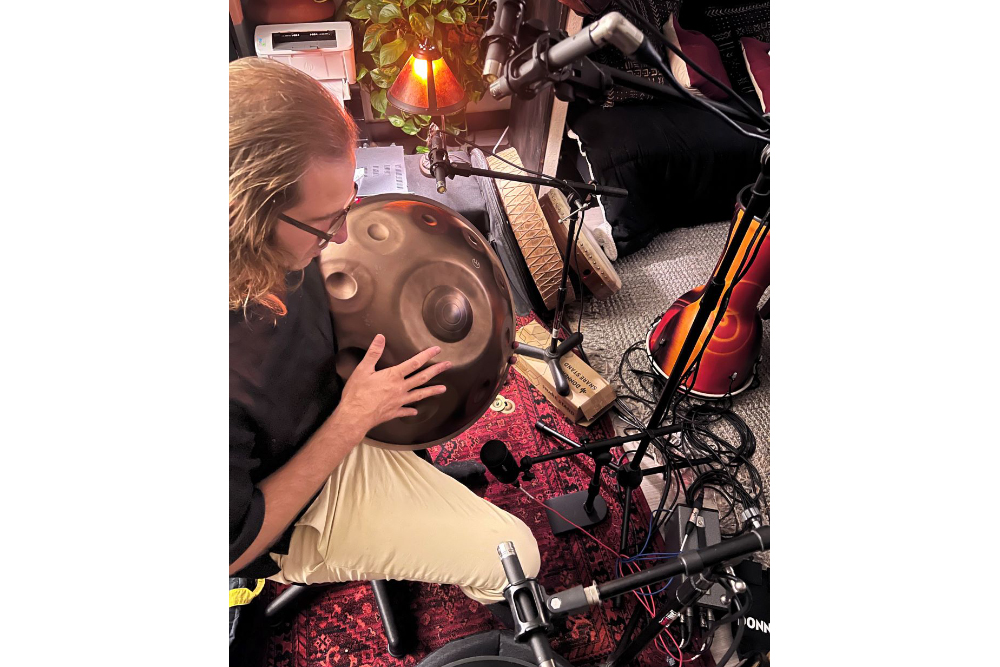

We recently had the opportunity to speak with a gentleman who operates such a facility. As he readily admits, his complex—consisting of four recording rooms and one control room – exists primarily to service his personal productions and projects. Unlike some, he does not advertise commercially, although the facility is available for rent to outside projects with the stipulation that he qualifies the types of projects and people who use his facility. They are, after all, entering his home.

Mr. X, who goes by that moniker at our request, is outspoken, opinionated, intelligent and highly representative of the attitudes we hear as we poll small facility owners, musicians, composers, and independent engineers and producers around the country.

Whether or not you’re comfortable with it, these rooms are having a positive effect on the industry. If history repeats itself, their genre will grow to fill in the boundaries of a much larger base strata. They are, to borrow a concept from the study of sociology and cultural development, the New Immigrants, or, if you will, the next generation. They may be commercially disenfranchised, but they are an economic power to both equipment manufacturers and the industry in general. Ironically, where they are today is also where so many professionally established studios were themselves, not too long ago.

Business Objectives

“I’m in the business of creating music. I’m not in the business of renting acoustically rarefied architecture and electronic signal manipulation devices. I don’t think that renting studio time only is a bad thing to be doing; it’s just not what I do for a living.

“Better than 50% of the activity in my room is my personal work, material that has my name on it. For me, it’s not a good idea to let the business of renting a studio take over my life. What I want to be doing is music. I don’t even want the studio to be too successful on its own.

“There is a crew of guys who come in to my studio regularly. Their material is spiritual, Christian music, very contemporary. They are first -class musicians, all of them. They actually make money off their material. At shows and events, they pack the house, big churches, to hear these guys play. After the performance, half of the people come up to buy tapes. It’s non-traditional distribution, but it works very well for them.

“What they need, and I provide at a viable price point, is the vehicle to get their stuff onto tape in such a way that it’s worth selling. When they come in, I am working with their organization as a producer, although I also function as an engineer and provide recording space. They wouldn’t be able to put out product at a viable economic rate if they weren’t working with a facility like mine.

“The people who come into my studio have no real alternative. They can’t afford to go to a ‘regular studio: The reason this facility exists for me is that my clients and I can’t afford other choices. They’re too expensive. They’re not too expensive for people who are doing work that is blessed by the high-end record industry or the broadcast industry. But if you are doing creative work that is outside that, then somebody is having to finance that situation out of their pocket. There is more work at that level in America than you think. A majority, I would guess.

“Before I owned my own gear, and long before I owned enough gear to let others record with me, I worked in regular commercial studios. Even when I was totally organized and prepared, when I hit a big studio, I was hustling. Forget about experimenting with this type of reverb against that kind of horn sound. Forget about it. Just do what you planned to do, because you can’t afford to do anything creative.

“Not to mention that at the end of all your money, you have one product to show. And your money is spent. Now I can spend 24 hours a day working on my stuff, and the gear is there tomorrow to continue. There is no end to the number of projects I can afford to do. The point is that you can’t go into a regular recording studio today and walk out with an artistic product for a reasonable, personally affordable amount of money. There’s no way that my Christian friends, who have a viable business and do it to support themselves, could generate the product that creates their business and get it to the point where it’s profitable.