Over the past 30-plus years I’ve been involved in numerous installation/integration projects. Some were bid jobs, most design build. The vast majority were completed successfully and profitably. There are always exceptions.

During this time I’ve watched hardware and software technologies dramatically change; customers come and go; and lots of key people move-on from general contracting, architectural and consulting firms. So, is there anything that hasn’t changed much? Yes. I believe it’s the concept or philosophy of having someone take ownership of each project.

The What, Why & How Of Project Ownership

Project ownership is a philosophy, an attitude, an ability and willingness to oversee all aspect of a project, and accept the “buck” when it stops on your desk.

Until just a few years ago, my primary role was working for integration firms as a systems designer specializing in audio, video and architectural acoustics. My forte was design/build projects where I was usually the sales engineer and design consultant. I responded to leads, engaged with customers, and often created and delivered a functional vision, design, and scope of work. Cost estimating, contract negotiations, commissioning, and training also fell to me. I “owned” the responsibility to make those projects successful for all concerned parties.

I’m not suggesting I’m the only one who would or could take ownership, the point is: someone must.

Project ownership – vis-a-vis the Project Owner (PO) – should be assigned to the one person who knows the project inside and out. He or she knows the customer and their needs and concerns; their budgets and schedules; the complete scope of work; and all the important decisions that where made along the way to land the contract and insure the customer received the quality, functionality, performance, aesthetics, ergonomics, timeliness, and value they expected and agreed to at the beginning. Collectively, these tangible and intangible items represent the perceived expectations of the customer.

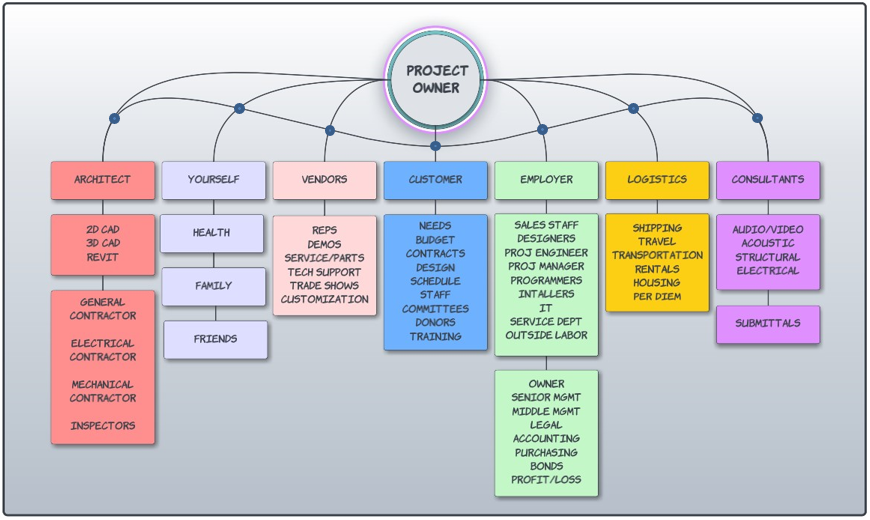

At the same time, the PO must also support the firm’s best interests: overseeing contracts, scope-of-work documents, design, engineering, submittals, vendors, purchasing, scheduling, install crews, logistics, programming, commissioning, training, project close-out and billing. To graphically illustrate all this, Figure 1 (above) shows my PO mind chart.

Ideally, the PO knows and interacts with all the key players from all the affiliated firms. He knows the products, the vendors, and the other players on his team, and, with some certainty, the logistical challenges. He has access to both the buy- and sell-side pricing of every piece of gear, and the profit expectations of his firm’s owners. The PO is the one person that everyone else can come to for answers, insights, justifications – and when needed – encouragement.

In my experience, AVA (audio, video, and acoustic) projects that don’t have a dedicated PO often fall well short of the desired goals of quality workmanship, transparent communications, timely progress, final completion, and profitability.

Is This Really Necessary? You Decide!

In a small firm, one person may have to own the roll for all projects. In larger firms, it’s best if there are enough POs to go around for each separate job. If needed, an experienced PO can usually manage three to four small- to medium-size projects simultaneously.

Some people can’t or won’t operate accordingly. Some think if you have good design documentation (plans and specs), anyone with the appropriate job description can step in at any time and take over any of the necessary tasks. I don’t subscribe to this approach. When was the last time you had flawless, airtight documentation? Never is a common response.

When there isn’t a PO the most common outcome is the he said, she said, finger pointing that arises when any significant questions or problems appear, mistakes are made, or delays occur. I’m fairly certain everyone reading this knows these don’t happen occasionally, they tend to happen multiple times on every project. If they don’t, you’re probably doing the same simple job over, and over.

The project ownership model isn’t for everyone. Mike Martin, VP of integration at Sound Image, says they approach things differently, using the AVIXA model. “We’ve adopted to not use a single project owner, to avoid someone having to be a hero. We opt for project team-member accountability, driven by their role and level of engagement through the project life cycle. We use a team approach where communication is key, and everyone knows their roles and responsibility throughout the course of a project. We try and avoid the ‘who’s in charge’ power struggle. Get everyone understanding who is playing a primary role versus a supportive role at different stages of the project. This gets everyone feeling a sense of involvement and importance in what we’re trying to accomplish.”

Controlling Custom Situations

On large and/or complex AVA integration jobs, almost everything is custom. I don’t mean the electronics – the overall integrated systems are customized for the customer’s unique applications and environment. The technology pairings, technical formatting needs and compatibilities, scheduling, budget, building codes, and logistics are often one of a kind. The architecture and acoustics may also have unique challenges. In short, custom.

The sales person, systems designer(s), project engineer, buyer, programmer(s), installers, equipment rentals, hotels, per diems, insurance, bonds, and contracts all have to be in sync, otherwise the project runs a high risk of losing money – or possibly failing completely. Each of these items is usually under the integrator’s control.

Things the integrator can’t control include the work and schedule of others, such as: the GC (general contractor), EC (electrical contractor), architect, structural engineer, electrical engineer, inspector, AVA consultants, and hardware vendors. All these need to play their part well in order for the “late trade” AVA team to have any chance of doing their work efficiently. If any one or more of these other consultants, vendors, or trades drops the ball, the AVA folks are the ones who suffer.

Managing Expectations

I believe the best way to survive in the AVA integration business is to actively manage the expectations of everyone involved. Literally everyone: the customer, your employer, your office staff, your field crew(s), your family, all vendors and reps, the architect, all consultants, the GC and EC, and yourself.

To successfully manage expectations throughout every step of the project, it’s vital to adopt and maintain an honest and pragmatic approach, present a positive attitude and tone toward your scope of work, and remain composed when all hell breaks out around you.

This is so much better than making unrealistic promises at every turn in order to appease an unknowing or unreasonable customer, GC, architect, vendor, boss, or spouse. The keys are to be wise, consistent, accurate, and reliable. Truth and pragmatism interweave to become your Kevlar vest.

And, to manage your expectations related to this subject matter, I plan to expound on this topic in a future article.

Who’s Best Suited To Be The PO?

Regardless of their job description or title, the best POs are the ones who willingly accept the position, and who consistently bring reality, humility, integrity, and attention to detail.

The sales engineer, design engineer, or project engineer may be the best choice because much of the information needed is easily accessible within the scope of their work. After a project is completed, a service manager may be best suited to own the ongoing relationship.

In any case, it’s appropriate to have the original PO linked in on service calls. I can’t count how many times a service call came in to me first. I was the person the owner or his key staff knew best. The one that hand-held the project from conception through birth; the one who’s name and contact info may be closest at hand.

It’s inevitable that a PO may leave your company. When this happens, it’s best to identify a new candidate quickly and have the departing PO brief the new person as thoroughly as possible. The new PO should then contact the customer and schedule a formal hand-off meeting. This will accomplish several positive agendas, namely:

1. Reconnect with the customer if it’s been a while.

2. Refresh all key contact information.

3. Demonstrate your firm’s willingness to provide excellent customer service, even when no new business is involved.

4. Give the customer a chance to ask questions, express frustrations, brainstorm about new project ideas, and/or share positive feedback.

Final Thoughts

Some might say the PO model is a euphemistic way of describing micromanagement. The way I see it, project ownership mainly involves being in a position to react to all aspects of a project’s needs in a timely, efficient, and effective manner. Directing traffic, anticipating problems, and making sure your staff has all the information and resources necessary to successfully do their specific jobs.

Is your daily routine chaotic? Do you work for a firm that doesn’t have, or won’t consider allowing anyone to adopt the PO role as described above? If so, it’s very likely no one on your team is taking on the responsibility of owning the various projects they’re contracted to do.

Are you, or have you been a PO without really putting a name to it? Do you think you’d make a good PO if allowed? It’s important to get approval from your company’s ownership/management before you proceed down this path. This too is a form of expectation management.

Project ownership can be tedious, frustrating, scary, and rewarding. If you’re the PO and a project goes well, a sincere thank you is often the best you can expect to receive. But, your employer will know, so too your team, your vendors, and your family and friends.

This is how a solid industry reputation is built: one project at a time.