If you’re looking for a prime example of what Toffler wrote about in Future Shock, look no further than analog tape. In a relatively short time span, the two-inch multitrack tape machine has gone from studio staple to relic rarity. And while many audio veterans wax nostalgic for that warm analog sound, few will admit to missing the work that went with it.

These days, owning an analog tape machine is somewhat akin to driving a classic car, with ongoing maintenance, scarcity of parts, and exotic fuel (analog tape) that’s expensive and hard to find.

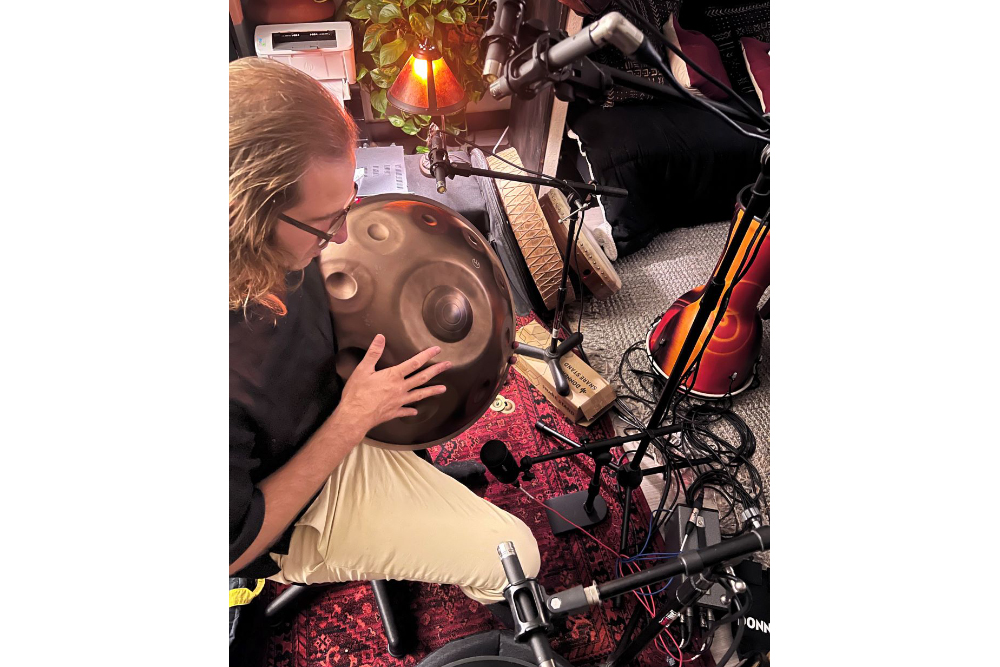

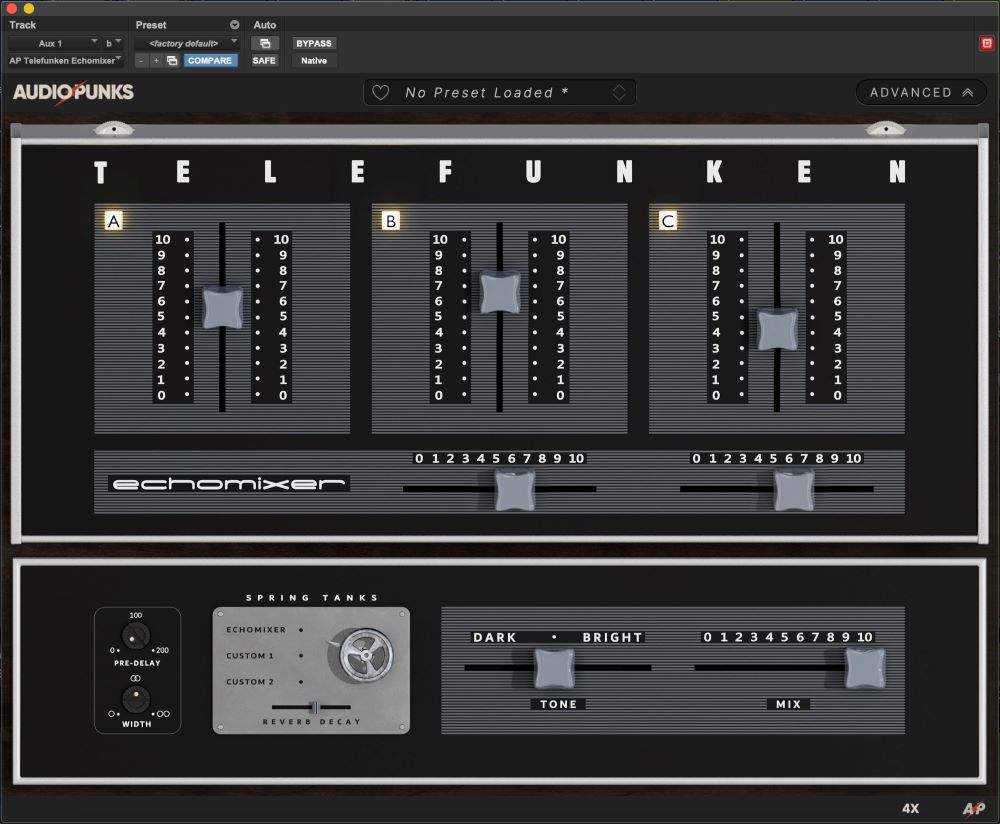

So while a handful of top studios still offer those classic spinning reels (and the engineers to maintain them), the good news for the rest of us is that there are now more convenient ways to achieve that classic magnetic sound.

A Bit Of History

The format offered two major advantages over the acetate disks of the day: a recording time of more than 30 minutes, and the ability for recordings to be edited. It was the first time audio could be manipulated.

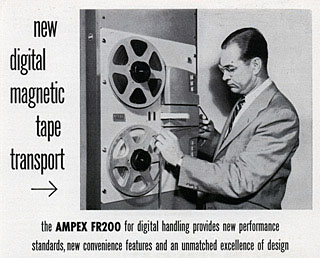

Mullin brought the two Magnetophons back home after the war and demonstrated them for Bing Crosby at MGM Studios in 1947. Crosby immediately saw the potential for prerecording his radio shows, and invested a small fortune of $50,000 in a local electronics company called Ampex to develop a production model.

Ampex and Mullen soon followed with commercial grade recorders. One of the first Ampex Model 200 recorders was given to guitarist Les Paul, who took the concept of audio manipulation to a higher level. Paul had already been experimenting with overdubbed recording on disks and, quickly realizing the potential for adding more channels and additional recording and playback heads, came to Ampex with the idea for the first multi-track tape recorders.

The format evolved from two tracks to three and four, and although Ampex built some of the first eight-track machines in in the late 1950s, most commercially available machines were limited to four tracks until 1966, when Abbey Road recording engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Townshend began experimenting with multiple machines during the recording of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Ampex responded to the demand the following year, introducing the revolutionary MM-1000, which recorded eight tracks on one-inch tape. Scully also introduced a 12-track one-inch design that year, but it was quickly overshadowed by a 16-track version of the MM-1000, using two-inch tape. MCI followed in 1968 with 24 tracks on two-inch tape, and the two-inch 24-track became the most common format in professional recording studios throughout most of the 1970s and 1980s.

With the prevalence of home and project studios and digital technology in the late 1980s and 1990s, a number of other tape formats emerged, including various multitrack on-reel and cassette configurations as well as multiple digital tape formats. But for the sake of this article, we’ll focus mainly on multitrack analog tape, the most sonically revered recording medium of all time.