I started out wanting to write about the design task of coming up with hybrid microphone and pickup rigs for Punch Brothers (a progressive acoustic band that I work with) and building a completely self-contained stage and mix system.

But that initial focus has changed, where I now feel the need to share some of what I’ve learned by plugging it in to many different sound systems, as well as offer some observations on stuff that works and stuff that does not.

Punch Brothers had been touring for several years with a carefully conceived “microphone only” system that worked very well in controlled concert situations, but we found ourselves seriously limited in many louder venues and made the decision to add pickups to it. The goal was to put together a “bulletproof” package that would work in every venue, everywhere.

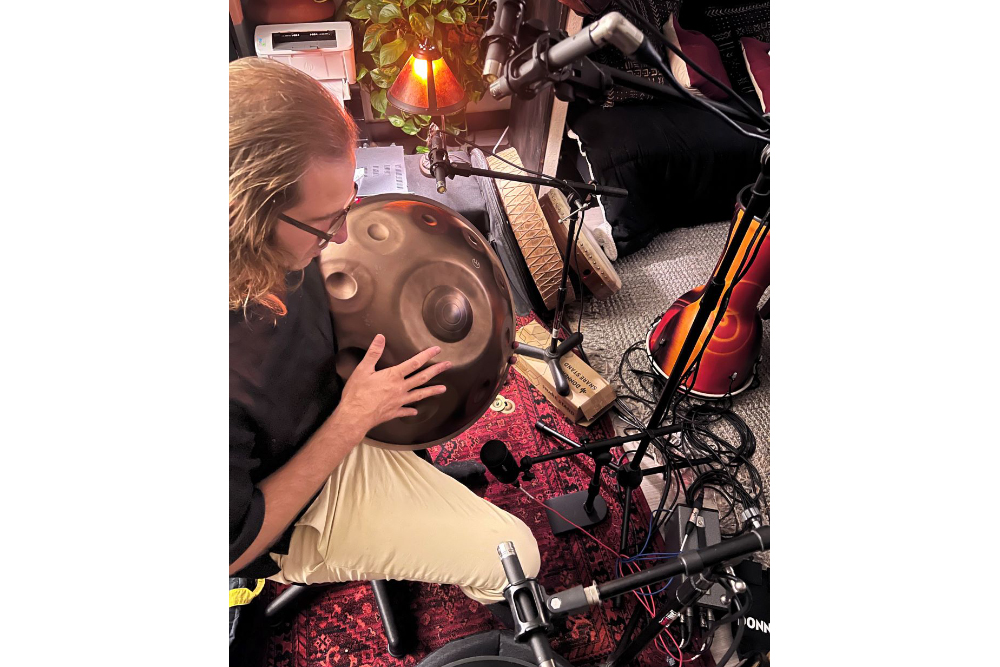

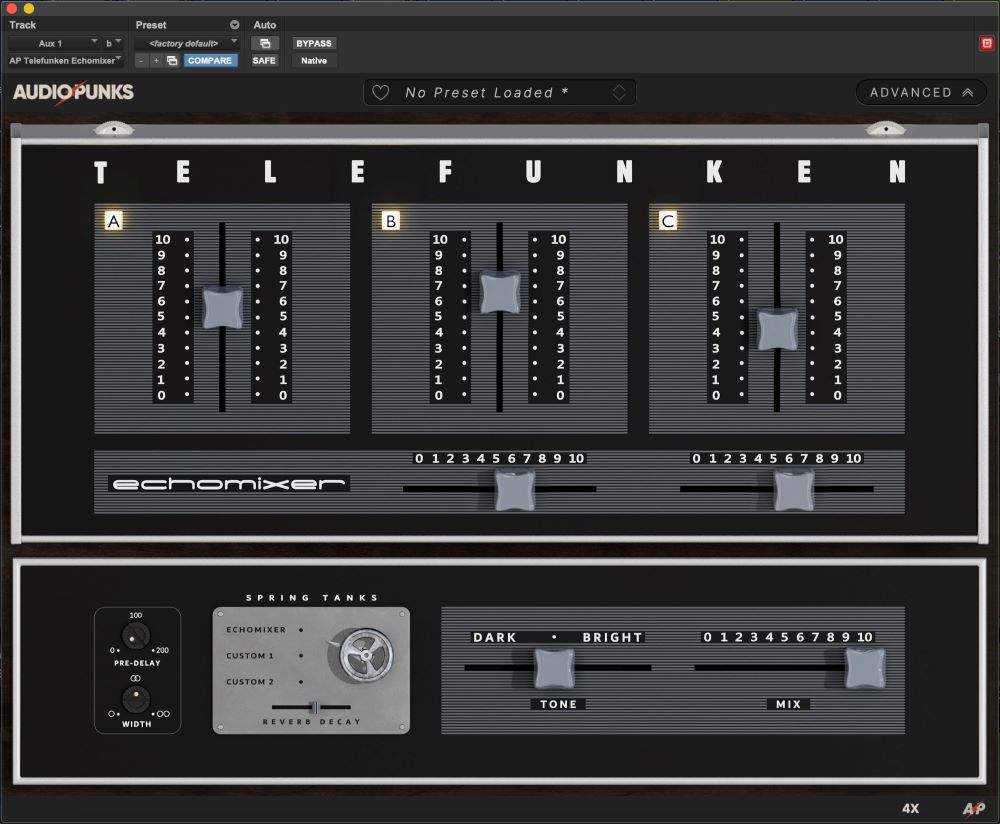

After much research and discussion, we booked time in a rehearsal room with a sound system and a pile of gear to build our pickup systems (despite our serious dislike of pickups) with a highly developed sense of what we thought the instruments should sound like. We tried various combinations of pickup, preamp, and effects with all of us sitting as jury, until everyone was satisfied with all sounds and our house mix output sounded as much like the record as possible.

This self-contained stage system included all stage wiring, monitor mixer with passive split, in-ear monitoring, pedal boards, front-of-house preamps, processing, and mixer all packaged to be checkable and able to fly. It was carefully designed to make setup and strike easy. and so that the only things that would change technically from show to show were the snake to FOH, the amps, the processing, and the loudspeakers.

Absolute Control

Amplifying acoustic instruments is always difficult at best, and having an entirely repeatable input scheme gave me an efficient way to judge the performance of sound systems and to avoid making corrections at the console that should be made on the system. It tended to make any kind of system problem readily apparent, and I became more aware of issues related to acoustic amplification that tend to be problematic.

First in line is a very general comment on amplifiers, loudspeakers and their associated processing. Most of the systems I encountered were technically adequate, but there were all too many that were optimized for loudness and then locked in the system processor beyond all discussion.

In terms of amplifying acoustic instruments I would argue that any equalization that is done in setting up a sound system, whether by ear or even by technical measurement, is completely subjective and does not relate to how my inputs will react on “this stage with this system.” I would go so far as to say that good amplified acoustic sound does not require fidelity in a sound system as much as it demands absolute

control of it.

All acoustic instruments are completely subject to their sonic environment. They require the application of energy to make mechanically produced sound. When the sound of the instrument is amplified with a mic or a pickup, the sound from the loudspeakers becomes additional energy applied to the instrument and microphone, creating a passive feedback loop between the main loudspeakers and the instrument, with a resonant peak consistent with that of the instrument itself.

The fact that this resonant peak occurs in the same frequency range where most sound systems have been beefed up to get loud makes for a double handful of energy to keep under control. This makes the term “flat” have little or no meaning in live sound and may be the main difference between recording to a reference loudspeaker and amplifying sound in a room.

Correcting these resonant peaks and feedback loops with input channel EQ is always the right place to start, but the cut made should be done equally in the main loudspeaker system as well, in order to avoid thinning (or reducing gain on) what is coming through the console too much. Keep in mind that finding that balance point between console and system EQ can be difficult with multiple loudspeaker systems and multiple inputs, but if you know that input sounds right at the console, you can lean more and more on system EQ – and even reduction of gain to the amps.

Sound systems that are optimized for loudness (which is most of them) are basically the opposite of what is needed for acoustic instruments. The fact that systems do have a lot of power in low mid and low end, and are often placed too close to the stage always makes it difficult to get a musical balance with an acoustic instrument.

By musical balance, I mean when the amplified instrument can play all notes in its range with the same perceived loudness in as many places as possible in the room. It’s always the interaction of the instrument with the system that dictates the degree of control needed. This contrasts sharply to a rock band that has very loud sound sources and directly synthesized sounds with little or no interaction with the main loudspeakers.

Key Interaction

Another issue that was encountered over and over in many systems was that of the efficiency of high-frequency response. The problem that kept appearing was that high-frequency levels on a system would sound perfectly fine until there was a dynamic peak with a lot of high-end content (a fairly common occurrence with acoustic instruments), and then it became very efficient on this peak, making the system far too bright.

In fact, I found this so often that I started calling it a syndrome, and in extreme cases, actually resorted to de-essing the entire system. Theories about why this might be happening include:

1) Perhaps the amplifier is too powerful and I’m barely driving it (over-powered system).

2) It could be as a result of individual system setups and their locked processors. Perhaps it’s also due to poor gain stage at some point in the chain, with some poor little op-amp at the edge of distortion. Or it could be a combination of all these things. To be fair, it did not happen with the best of the systems, and particularly, the lovingly maintained older systems.

Being blessed with no monitors on stage, and after having determined that all loudspeakers were working, my first order of business was always to check the interaction between the mains and the stage. This interaction is the single largest limiting factor in amplifying acoustic instruments. I deal with it by tuning the system like a giant stage monitor, and on problem stages, sometimes resorting to altering the phase relationship of individual inputs. In really bad situations where the system involves the entire stage, the only recourse is to turn it down.

Loudspeaker placement is always dictated by space and sight lines, but unfortunately also by things like the length of the lighting truss and even worse, by someone’s sense of aesthetic: subwoofers and stacks on stage, or loudspeakers coupled in any way to the stage, are the “worst case scenario” of loudspeaker interaction, and it means you’re going to have a bad day.

Many older loudspeakers radiate large amounts of low and low-mid behind them, and there are venues where the loudspeakers are hanging just a few feet over the stage. Poor placement presents the biggest challenges, with a huge effect on acoustic instruments, and it’s found regularly in venues around the world. In defense of those who decide where to put loudspeakers, while there might be other options, these are often extremely expensive to achieve. I’ve found that loudspeaker placement relates directly to my level of perspiration during a show and degree of satisfaction at the end.

Placement of mains often leaves an area of poor coverage along the front of the stage and sometimes out into the center of the room, requiring front fill. These situations are the real wild card in amplifying acoustic instruments, with the potential of being the most interactive and likely to change their relationship to microphones on stage when a wall of people line up in front of them.

A front fill system should always have its own EQ separate from mains at FOH. just like a monitor mix. Wedge mixes for acoustic instruments should always be from post EQ mixes from FOH and not from a monitor desk on stage. If all loudspeaker systems, including monitor wedges, are balanced properly, then the input channel EQ becomes the master, allowing you to compensate for loudspeaker interaction in the right place.

Separating stage and house sound with acoustic instruments can work in some places, but I would argue that it’s better to treat it as one system. No stage monitors or IEM systems provide maximum control at FOH, and any additional loudspeakers that do not follow input EQ from FOH will degrade overall quality in the room with the addition of its energy to the feedback loop. This can easily lead to overcompensating at the console and system EQ.

I’ve seen many different configurations of front fill, but by far the most effective placed the loudspeakers just off stage, mounted as high as possible above the heads of the audience, and angled in and down towards down stage center. I do not agree with delays on front fills on most stages, and usually push them as far upstage as possible and closer to the band to get less delay.

Control of front fill can often be the key to having good sound, particularly in very ambient rooms. Even a slight shift of level from the mains into the front fills can make an acoustic instrument sound more believable by balancing sources of energy in the room making it feel like there is more coming from the stage.

The biggest problem with front fills (mostly with standing audiences) is the sometimes enormous change that occurs in their relationship with the stage when people are standing in front of them. The change can be minimized by placement, but I hover over the front fill EQ at the top of every show to compensate for the change that I know the audience will generate.

Level Considerations

I’ve put a lot of thought in to what many call “saturating the room.” I’m referring to that point of loudness, particularly in more reverberant rooms, where reflections seem to equal or even exceed what is coming from the loudspeakers – and everything turns to mush. This phenomenon is caused not by the acoustic qualities of the room, but by the fact that we hear longer “tails” on louder sounds.

How loud you can mix is directly related to the density and quality of the reflections in the room. Most rock clubs have dealt with this by deadening the room and optimizing high frequencies in the system to restore clarity and detail, but in a concert hall it can happen at a very low level. The only way to avoid it is by turning everything down, and focusing on tone instead of loudness. An empty room can also suffer extreme loudspeaker placement problems like excessive comb filtering or bad flutter echoes that can completely disappear when the audience is in place.

There are now many concert halls that have seating designed to minimize the difference between empty and full rooms, but that’s really all they do. The effect of an audience on amplified sound is something I never tire of experiencing. It’s subtle in some rooms and very pronounced in others, but always there, and always makes it better.

What I observe to be happening is a change in the way sound energy is moving in the room, particularly in terms of how the loudspeakers are interacting with the stage. This is partly about the front fill issue, but also about how the house sound is reflected off or absorbed by the audience, the ambient temperature and humidity, and the expectant energy they bring with them. This all has a profound effect on how much sound level the room will support and will always offer more than an empty room sound check.

Eliminating Variables

So several hundred sound systems later, after balancing and tweaking and fixing and moving, some things are very clear to me in the amplification of acoustic instruments. The physical arrangement and setup of a sound system – and it’s relationship to the stage – is the most important factor in getting a musical balance.

Further, the choice of optimizing for what is coming out of the loudspeaker instead of how the loudspeaker is presenting itself to the room can make this job much tougher. Making an entirely isolated sound source astonishingly loud on a loudspeaker is easy, but tuning multiple feedback loops to achieve a musical balance is remarkably difficult.

In eliminating as many variables as possible on what I was plugging in to a sound system, it became easier to get this balance and to isolate problems. Instead of building an input structure to accommodate the loudspeakers, I’m manipulating the sound system to balance in a musical way with my input structure.

One aspect that clearly stands out at every show and on every system: any change in any loudspeaker system that’s in conflict with what the musicians need to hear to play properly is simply wrong. The technical side of amplifying sound in a room should always act in support of what is going on musically and not just in regard to playback fidelity. Just like an acoustic instrument is entirely reactive to the space it is in, so should be the sound system making it louder.