The Tape Transport

The process of recording audio onto magnetic tape depends on the transport’s capability to pass the tape across a head path at a constant speed and with a uniform tension.

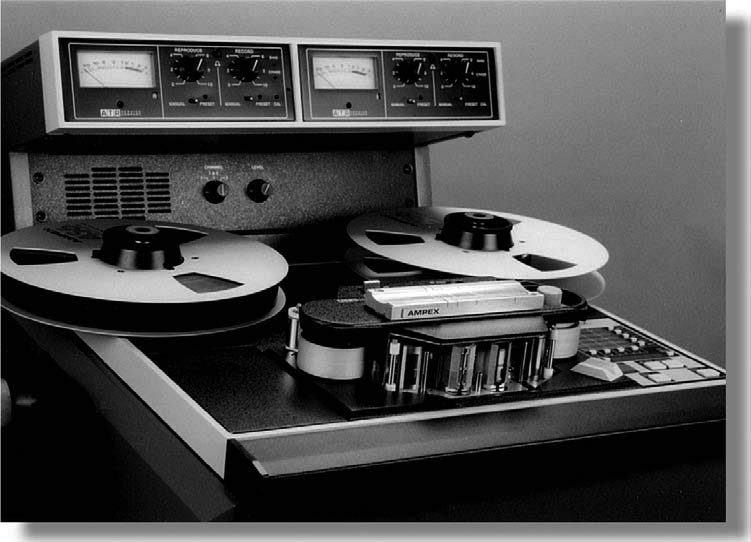

In simpler words, a recorder must uniformly pass a precise length of tape over the record head within a specific time period (Figure 8).

During playback, this relationship is maintained by again moving the tape across the heads at the same speed, thereby preserving the program’s original pitch, rhythm and duration.

This constant speed and tension movement of the tape across a head’s path is initiated by simply pressing the Play button.

The drive can be disengaged at any time by pressing the Stop button, which applies a simultaneous breaking force to both the left and right reels.

The Fast Forward and Rewind buttons cause the tape to rapidly shuttle in the respective directions in order to locate a specific point.

Initiating either of these modes engages the tape lifters, which raise the tape away from the heads (definitely an ear-saving feature).

Once the play mode has been engaged, pressing the Record button allows audio to be recorded onto any selected track or tracks.

Beyond these basic controls, you might expect to run into several differences between transports (often depending on the machine’s age). For example, older recorders might require that both the Record and Play buttons be simultaneously pressed in order to go into record mode; while others may begin record- ing when the Record button is pressed while already in the Play mode.

On certain older professional transports (particularly those wonderful Ampex decks from the 1950s and 1960s), stopping a fast-moving tape by simply press- ing the Stop button can stretch or destroy a master tape, because the inertia is simply too much for the mechanical brake to deal with.

In such a situation, a procedure known as “rocking” the tape is used to prevent tape damage.

The deck can be rocked to its stop position by engaging the fast-wind mode in the direction opposite the current travel direction until the tape slows down to a reasonable speed … at which point it’s safe to press the Stop button.

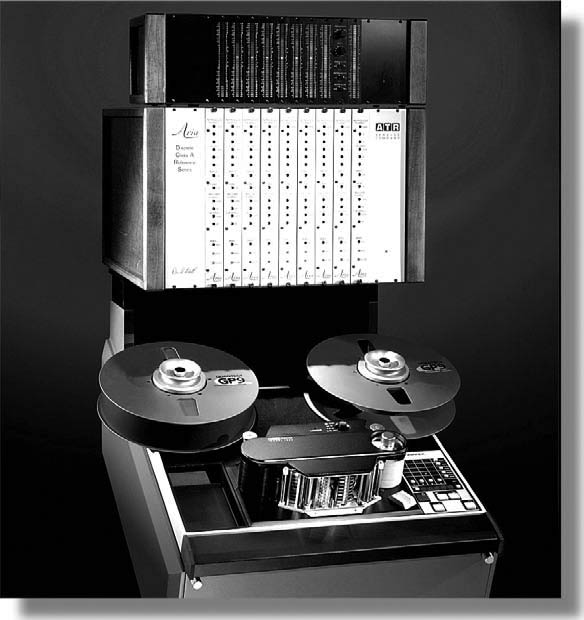

In recent decades, tape transport designs have incorporated total transport logic (TTL), which places transport and monitor functions under microprocessor control.

This has a number of distinct advantages in that you can push the Play or Stop buttons while the tape is in fast-wind mode without fear of tape damage.

With TTL, the recorder can sense the tape speed and direction and then automatically rock the transport until the tape can safely be stopped or can slow the tape to a point where the deck can seamlessly slip into play or record mode.

Most modern ATRs are equipped with a shuttle control that enables the tape to be shuttled at various wind speeds in either direction.

This allows a specific cue point to be located by listening to the tape at varying play speeds, or the control can be used to gently and evenly wind the tape onto its reel at a slower speed for long-term storage.