Magnetic Recording And Its Media

At a basic level, an analog audio tape recorder can be thought of as a sound recording device that has the capacity to store audio information onto a magnetizable tape-based medium and then play this information back at a later time.

By definition, analog refers to something that’s “analogous,” similar to or comparable to something else.

An ATR is able to transform an electrical input signal directly into a corresponding magnetic energy that can be stored onto tape in the form of magnetic remnants.

Upon playback, this magnetic energy is then reconverted back into a corresponding electrical signal that can be amplified, mixed, processed and heard.

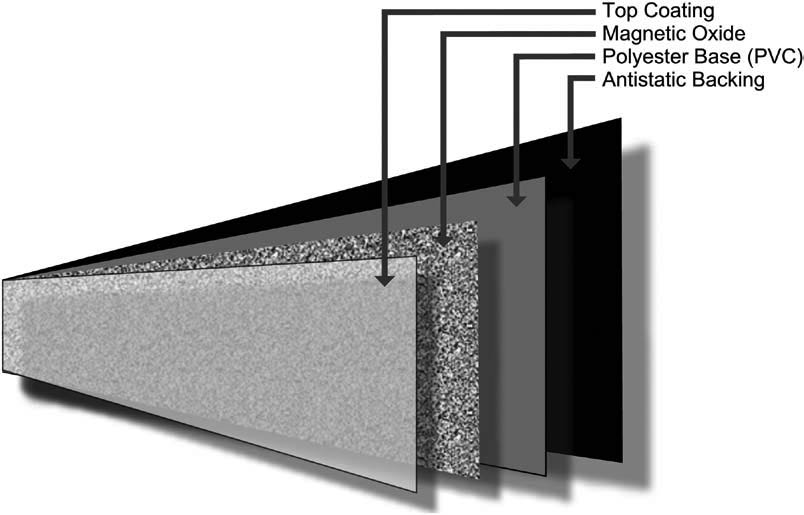

The recording media itself is composed of several layers of material, each serving a specific function (Figure 2).

The base material that makes up most of a tape’s thickness is often composed of polyester or polyvinyl chloride (PVC), which is a durable polymer that’s physically strong and can withstand a great deal of abuse before being damaged.

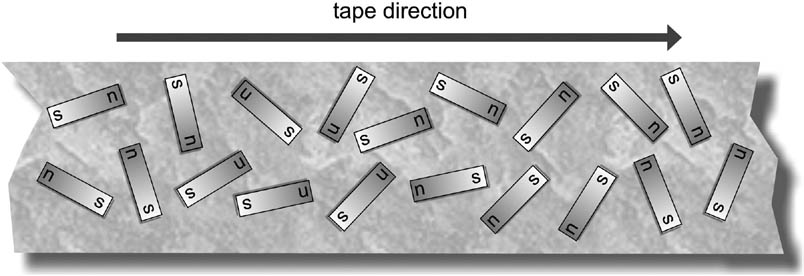

Bonded to the PVC base is the all-important layer of magnetic oxide. The molecules of this oxide combine to create some of the smallest known permanent magnets, which are called domains (Figure 3a).

On an unmagnetized tape, the polarities of these domains are randomly oriented over the entire surface of the tape.

The resulting energy force of this random magnetization at the reproduce head is a general cancellation of the combined domain energies, resulting in no signal at the recorder’s output (except for the tape noise that occurs due to the residual domain energy output).

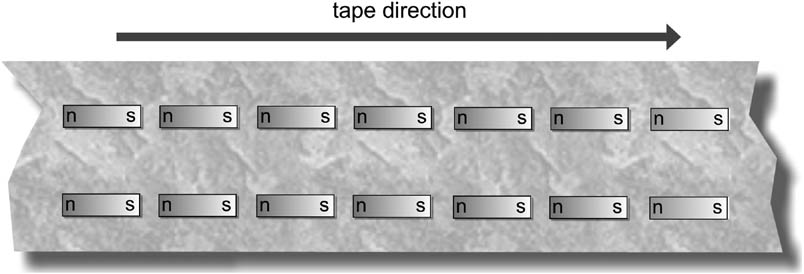

When a signal is recorded, the magnetization from the record head polarizes the individual domains (at varying degrees in positive and negative angular directions) in such a way that their average magnetism produces a much larger combined magnetic flux (Figure 3b).

When the tape is pulled across the play- back head at the same, constant speed at which it was recorded, this alternating magnetic output is then converted back into an alternating signal that can then be amplified and further processed for reproduction.

The Professional Analog ATR

Professional analog ATRs can be found in 2-, 4-, 8-, 16- and 24-track formats. Each configuration is generally best suited to a specific production and postproduction task.

For example, a 2-track ATR is generally used to record the final stereo mix of a project (Figures 4 and 5), whereas 8-, 16- and 24-track machines are obviously used for multitrack recording (Figures 6 and 7).

Although no professional analog machines are currently being manufactured, quite a few decks can be found on the used market in varying degrees of working condition.

Certain recorders (such as the ATR-108C 2-inch, multitrack/mastering recorder) can be switched between tape width and track formats, allowing the machine to be converted to handle a range of multitrack, mixdown and mastering tasks.