This excerpt is the first in a series from Bruce Swedien’s book Make Mine Music by Hal Leonard.

Microphone Design Technology And Microphone Technique

Along with this development of a more live sound and hi-fi in the popular recorded music of the early 1950s, a great deal of experimentation and improvement in microphone placement and technique was going on at the same time. Much energy and effort were put into the development of innovative microphone design.

American microphone design technology and microphone technique were handed down from the broadcast industry to the recording industry, and were definitely ready for experimentation and improvement.

Many of the so-called unidirectional and bi-directional mikes of the time were actually omnidirectional in the low-frequency range of the audio spectrum. Of course, this only accentuated the problem of too much reverb time in the low-frequency end of the spectrum in the day’s major recording studios.

To further intensify this low-end “coloration” of recorded music, the off-axis response of most of these older mikes caused very unpleasant and unmusical-sounding time and spectral coloration of the sound.

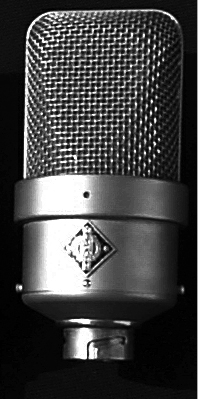

As microphone placement technique underwent radical and welcome experimentation and improvement in the early 1950’s, the introduction of exotic, new microphones, such as the Telefunken U 47 from Germany greatly improved the recorded sound of music.

In the fall of 1951, I was attending classes at the University of Minnesota. Walking from class to class on the campus, my schedule took me close to beautiful Northrup Auditorium. A large concert hall with wonderful acoustic qualities, Northrup Auditorium was, at that time, the home concert stage for the Minneapolis Symphony (then under the baton of Antal Dorati).

As a kid, I had attended Minneapolis Symphony concerts almost every Thursday evening, with my mom and dad, at a time when Dimitri Metropolis conducted the orchestra. The sight of that big, lovely concert hall reminded me of the fantastic sound of the orchestra in such wonderful acoustics that I had heard as a youngster.

Telefunken U 47

While at the University of Minnesota, I worked part-time at KUOM, the University radio station. Every Sunday afternoon, KUOM broadcast the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra in concert (in mono, not stereo).

One day in the KUOM studios I met a man by the name of Bob Fine, a recording engineer from New York who was in Minneapolis to record the Minneapolis Symphony for Mercury Records. He had in his hand a black box that resembled a miniature coffin.

This important-looking little black case was about 10” long, 2-1/2” wide, and about 2” high. Bob opened the case, and resting in it on a little bed of dark blue velvet was an absolutely gorgeous German microphone. Bells went off in my head!

I had never seen anything like it in my life before! It was the Telefunken U 47 microphone! I was most definitely in love!

I was, of course, very impressionable at the time, but I will never forget the sight of that exotic-looking microphone with its handsome chrome top and impressive machined metal-and-rubber shock-mount.

I couldn’t wait to hear how it sounded! Every time I look at my Telefunken U 47s now, my mind flashes back to that moment. Bob took the mike out of its case and showed it to me. He explained a bit about how it worked and how he was using it suspended 10′ above Mr. Dorati’s head. That way, the microphone “heard” the orchestra in virtually the same balance as Mr. Dorati did.

This concept in microphone design, with its extremely wide and smooth frequency response, was almost like a miracle to me!

I had used condenser microphones before, but the Altec 21b condenser mike that we had at Jay Kershaw’s little basement studio didn’t sound anything like this! Bob let us use the mike for a few days while he was there, to broadcast the Sunday symphony matinees on KUOM. The sound was absolutely fantastic!

I recall that there were also some television broadcasts of the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra from Northrup Auditorium using that Telefunken microphone at about the same time. The use of this incredible mike was explained in detail on the TV program, and I remember watching and listening in rapt delight.

Here are a couple of interesting facts about one of my most cherished microphones, the Neumann U 47:

I later learned that the Germans had been experimenting with and had actually produced microphones of close to this fantastic quality 15 years earlier.

The Neumann U 47 was the first post-war mike produced by Georg Neumann GmbH in West Berlin. It was designed around a World War II military radio tube (that probably was in great supply at very low-cost) with a capsule design from 1929!

About 10,000 U 47s were made. It became the “benchmark” expensive (at $390) microphone in the early 1950’s, and engineers found out quickly that the sensitivity of the U 47 greatly enhanced the detail of their recordings.

The U 47 was a very popular vocal mike. There were many U 47s (and U 48s) used for the famous Beatles recordings, and George Martin, the Beatles’ producer, wrote that the U 47 is his favorite mike.

U 47s are pictured in abundance in the Beatles’ recording studio photos. Their aggressive sound makes them an excellent choice for lots of rock applications. Drums, guitars, amps, and brass instruments shine when sitting behind a U 47!

I bought my first pair of Telefunken U 47 mikes in 1954, from American Elite in New York, while I was still living in Minneapolis (I still have all the original paperwork). They were a bit unusual in that they are the long-body, nickel-grille version. When those fantastic mikes arrived, it was a very big day for me. I was only 20 years old, and my two Telefunkens were the only U 47s in Minneapolis (I’m sure Bill Putnam had some Telefunken microphones in Chicago).

One of these precious mikes was stolen while I was working on Michael Jackson’s Thriller in 1982 (it’s one of his favorite vocal microphones). To this day, I use my remaining Telefunken U 47 on almost every project I am involved in. Isn’t it incredible that even today, this wonderful microphone is still often the first choice for miking many sound sources?

Now, let’s take a bit of a journey back in time with my Neumann U 47. It was in the early 1950s that we began in earnest to attempt to improve the actual studio set-up of the musicians, singers, and microphones.

We abandoned many of the handed-down studio and microphone techniques of the past that had come from the radio broadcast industry. In the early 1950’s, microphone placement technique underwent radical and welcome experimentation and improvement.

At the same time, the introduction of exotic, new microphones, such as the U 47 greatly improved the sound of recorded music. The U 47 was probably the first microphone designed specifically for ultra-high-quality sound recording, with music recording as its primary intended use.

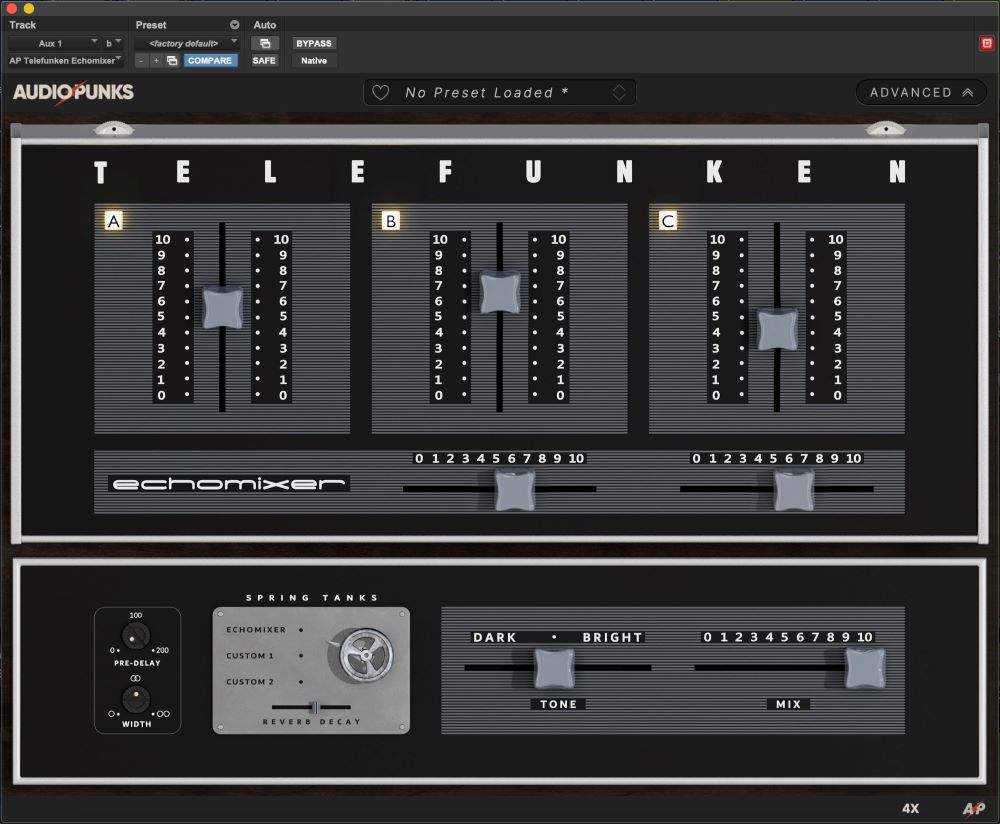

The Neumann Model M 49

A few years later, Telefunken introduced the Neumann model M 49 condenser microphone, another exotic model from Germany. This is another of those wonderful microphones that is still in use today in the best world-class studios.

Designed in 1949, the M 49 was introduced to the buying public in 1950 as the answer to the question, “U 47?” It is a continuously variable multi-patterned, large (approx. 1”) dual-gold diaphragm microphone using the Telefunken ac-701 or ac-701k tube as its hub.

It had three different stand mounts, and it came in a variety of boxes. There were various models, including the M 49, M 49b, M 49c, M 249b, and M 249c.

The M 249b and M 249c were designed with an RF (radio frequency) suppression-type screw-on connector designed for the German broadcast industry. They usually utilized a “cassette system” power supply known as the N-52.

The M 49 is a superb vocal mike, but may be used for many other applications, from miking an electric guitar amp to recording French horns! Because of its adjustable polar patterns, it can be used in everything from omnidirectional mode for room miking to figure-8 for background vocals.

The Different Colors Of The Neumann Logo

Here are some small, but highly interesting facts. I love little historic details like the following:

There is a significance and meaning of the different colors of the Neumann logo on the various models of Neumann microphones.

Beginning with the Neumann “Bottle” microphone, the CMV 3, in 1928, Neumann microphones sported a logo with a black background. This was used with all vacuum-tube-equipped microphones. For this reason, the microphones from the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s feature the black logo, as well.

Beginning in 1966, the first transistorized (solid-state) microphones were offered by the Neumann company. This was the 70 series for 12-volt A-B powering (also known as T-powering), with the models KM 73 through KM 76, plus the U 77 switchable-pattern model. For this series, the black logo was retained.

With the introduction of the microphones of the 80 FET series in the mid 1960’s, the 48-volt phantom power system was launched, and these microphones were identified by their purple Neumann logo.

The prime example of this series is the U 87. My personal favorite of this series is the U 47 FET. I have two U 47 FETs, very close in sequence numbers, that sound simply fabulous! I absolutely treasure these lovely mikes.

The currently used red Neumann logo signifies microphones with transformerless electronic circuits of the 100 series (e.g., the KM 140, TLM 170 r, RSM 191, TLM 193, or the KM 184) and TLM series.

Here’s Something To Think About:

“No sound system, no sound product, no acoustic environment can be designed by a calculator. Nor a computer, nor a cardboard slide rule, nor a Ouija board. There are no step-by-step instructions a technician can follow. That’s like Isaac Newton going to the library and asking for a book on gravity. Design work can be done by designers, each with his own hierarchy of priorities and criteria. His three most important tools are knowledge, experience, and good judgement.”

That quote is from Ted Uzzle, a Harvard-educated design consultant for motion picture facilities in Hollywood from 1973 to 1980 who joined Altec Lansing in 1980, was made a fellow of the Audio Engineering Society in 1984, and became editor of S&VC (Sound & Video Contractor) magazine in 1992.

Innovative Placement Of The Musicians And Microphones

In early 1950, in an effort to improve the separation of musical instruments in music recording, the reverb time of modern studios was reduced. A concerted effort was made by major-label and independent music recording studios alike to reduce the reverb time in the middle and lower frequencies.

It was also at this time that we began to use acoustical separation screens or isolation flats, or “gobos” – or whatever we wanted to call them. These acoustical isolators were placed between instruments or whole sections of the orchestra to improve the definition and separation of the sound sources in a recording.

Using acoustical dividers in this manner made it possible for the microphone (or microphones) to be focused on a single musical instrument or group of instruments, and thus minimize the acoustic interference of other instruments playing at the same time.

In the 1930s and 1940s, the musicians and singers were arranged in the recording studio in an almost concert-like setup, and little or no effort was made to achieve clarity or apparent separation of sound sources in music. As a result, the sonic images of the musicians and singers in many old recordings is rather blurred and indistinct.

The year 1950 was the beginning of a very important decade for recorded music. With the release and incredible success of Les Paul and Mary Ford’s “How High The Moon” in 1951, it seemed as though a big section of the record-buying public was no longer interested in cold reality in popular music.

As the 1950s came to a close, we in music recording found that reality in sonic image was not necessary, and perhaps not even desirable. This innovation and improvement in technique actually began in the very early 1950s, although when I began my work at Universal in Chicago in 1957, this renaissance in mike technique and studio setup was still very much in evidence. It was a wonderfully exciting time to be learning.

As a youngster in my early twenties, every minute of every day was full of new experiences in the studio. The big bands and musical artists that I worked with every day were very much in love with the recording process.

This excerpt is the first in a series from Bruce Swedien’s book Make Mine Music by Hal Leonard.