If you’ve never experimented with double-miking a musical instrument, you’re in for a treat. Properly utilized, the technique provides a whole new palette of tonal colors, along with surprising ease of control. It’s especially useful when working with an unfamiliar console, one that has limited EQ capability, or when multiple operators are working together on the same control surface.

Further, with two or more microphones on key instruments, there is built-in redundancy. If one mic fails, falls off its stand, or gets whacked by a drum stick, mic number 2 is likely to still be in-service and able to keep the show going along relatively unscathed. For this reason, it’s a good idea to mix condensers with dynamics whenever possible, so that a failure of a phantom supply won’t cause both mics to go down.

Let’s start with kick drum, as it provides the foundational anchor for many modern musical styles. Certain shell materials, heads, and beater combinations can lack definition, sounding big but muddy and indistinct. Or at the other end of the scale, definition might be fine but the desired low-frequency “whoomph” is less than inspiring.

The usual practice of placing a single mic in front of the outer head or the sound hole (if there is one), or inside the shell on a pillow, may not provide the desired sonic quality – though each position will certainly produce different tonalities.

But even if you find a sweet spot with a single mic, you may not want that same tonality for every song, or you might have settled for a tonal compromise to begin with. Traditionally the problem is solved by applying EQ, maybe also a compressor and a gate, or endlessly changing out mic types to try to get closer to the mark. But there’s another way. It’s faster, easier, and comes with collateral benefits that solve other problems at the same time.

On The Kit

With more than one mic to work with, it’s possible to create a wide range of tonal colors merely by blending the channel faders together proportionally to obtain the sound quality you’re after.

In practice, the technique is fast and simple. Depending on the sophistication of the console, the relative levels can either be recalled by using presets for different songs or, on a modest analog mixer, the useful range of relative levels can simply be marked on tape alongside the faders. The only downside is the requirement for additional mics, multi-core channels, and console inputs.

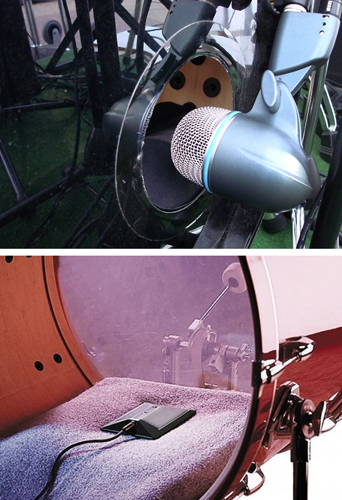

I’ve found that the combination of a “half-cardioid” mic, such as a Shure Beta 91A placed inside the kick drum, coupled with a traditional dynamic cardioid such as a Shure SM7B or a Beta 52A located outside the sound hole or near the center of the front head, are a solid pairing.

The 91A inside the shell captures a sharp, well-defined attack, while the SM7B outside the shell provides punch, and with a bit of EQ it can add a good measure of “thunder” when it’s needed.

It’s no rarity to see a snare miked from both the top and bottom heads. This is perhaps the most common usage of dual-miking and again gives the mix engineer a lot to work with. Want a more snappy sound to cut through screaming guitars? Increase the level of the bottom mic. Need to mellow it out some? Take the bottom mic down or out altogether. Try an AKG C451 on the bottom head and an SM7B on the top. Then reverse their positions and see what happens. It can be an ear opener. By blending the two faders together in different ratios, it’s possible to radically alter the timbre without ever touching the EQ, which can be held in reserve for creating additional layers of sonic potentialities.

Other mics can accomplish much the same thing while adding their own particular “flavor.” Good candidates are the AKG D12 or Electro-Voice RE20 used outside the shell, paired with an AKG C547 or Audio-Technica U851R inside the shell. The real value here is making use of the differences in physical placement and the differing types of the mics, rather than adhering to specific models.

The same concept can be applied to toms, especially if they’re fitted with bottom heads. Depending on how the toms are tuned, there can be significant differences in what each mic picks up, thus creating an opportunity for making the toms sound larger than life on one end of the scale, or providing only mild accents on the other end. All without using EQ.

In situations where time allows, such as preparing for a lengthy tour, installing mics inside the shells will provide tremendous isolation from drum to drum, as well an extremely sharp attack that you can’t get from exterior miking.

However, the mids and lows tend to be very thin, so additional support is likely to be needed from exterior mics. On a big kit this might eat up a lot of channels, but if they’re available, the level of control you’ll experience is astounding.

You can even delay the exterior mics by a few milliseconds relative to the interior mics, producing the effect of a bigger and longer “body” that follows the impact of the initial stick contact. This is highly recommended for complex, demanding music such as fusion and progressive rock.

Spreading The Concept

Other percussion instruments can also benefit from a double-miking approach. Try miking both the top head and the bottom flare of a djembe. Listen to what happens. The depth of LF content from the bottom mic will put to shame many large-diameter kick drums. The modest djembe now becomes a powerhouse!

The same approach can also be applied to congas whenever a “power factor” is desired. (If recording, be sure to allocate two tracks for maximum flexibility when mixing.)

If a system is configured in stereo, there’s nothing like a pair of mics positioned over the tray of percussion “toys.” When a shaker is being moved around the stereo pair, the wide expanse and motion of sound in the loudspeakers can be breathtaking. If taking this approach, it’s important that the percussionist has stereo stage monitors in order to provide some idea of the effect the movements are having on the spatial localization in the main system.

When a traditional lead instrument is present – one that plays an important role in the music such as a sax, trumpet, clarinet, or flute – miking in two places can capture the essence of the instrument’s voice in a way that no amount of EQ will achieve. A lot of tone emerges from traditional instruments, and it’s not all coming from the bell or the mouthpiece.

On a large baritone sax, for example, the lower part of the instrument often provides a resonant character that’s an important component of the sound the player is hearing and working off of. Fortunately, with today’s miniature clip-on mics and readily available wireless transmitters, it’s not as hard as it once was to capture the very best that a given instrument has to offer without cramping the stage movements of the performer.