There are some real advantages to parallel compression, something that I really got into a couple of years ago when we got a DiGiCo SD8 console.

But first, let me give you a little history and explain some terms, and then I’ll show you what I’m doing. I’ll be the first to say I’m not an expert, but it’s been a lot of fun learning the technique and playing with variations of it.

A Brief History Of Comps

There is some debate over where this technique originated. It’s often known as “New York Compression” as it was used heavily in the NY mixing scene during the ‘70s and ‘80s.

Others say the technique is over 40 years old, having been employed in Motown to help vocals stand out over the much more complex musical background of that style of music. If you listen to earlier samples of music (think Frank Sinatra), you’ll hear the vocals way out in front and a sparse musical landscape way in the back.

When the much busier style of Motown music came along, it was hard to get the vocals to sit out front; they were getting lost in the mix. Parallel compression was employed to fix that. That’s basically how I use it today. You can read more about the Motown history of parallel compression in this great article (props to Jeremy Carter for digging it up). Either way, it’s a greatly useful technique for enhancing your mix.

Defining Terms

We throw around a bunch of terms when we’re talking about parallel compression—double patching, double busing, smashing, spanking, bus with a comp—so let me see if I can clear some of those up.

Double patching is how we achieve parallel compression. Basically, we patch the same mic into two channels and process them differently. On an analog console, this can be done with a simple Y-cable. On a digital console, you just patch the same input into two channels. In either case, one channel gets a heavier comp, the other is processed normally.

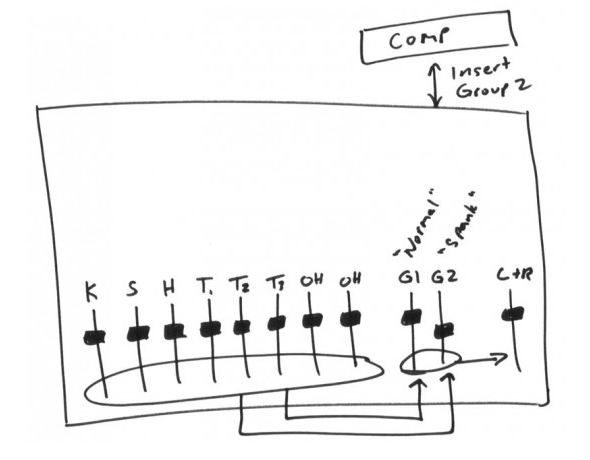

Double busing is used if you’re working with multiple inputs that you want to parallel compress, you bus them the two separate groups; again, one is normal, one gets the comp treatment. I’ll talk about why you might want to do either method in a moment.

Smashing is a colloquial term for parallel compression. When someone has a vocal smash channel, it’s typically created with parallel compression. Because we typically employ pretty significant amounts of gain reduction to the channel (10-15 dB of gain reduction), it is said to be “smashed.”

Spanking is something that I consider a milder form of smashing. On some level, I’m making up definitions of terms here, and others may define them differently. But for our purposes, spanking is like a smash, only with less gain reduction, perhaps 6-9 dB.

Bus with a Comp is a variant I learned from my friend Dave Stagl. A group of channels is sent to one bus with little or no processing, and another one with a comp inserted. This is perhaps the most mild form of parallel compression, as when Dave says “a bus with a comp” he’s only doing 4-6 dB of gain reduction (maybe less). It’s a pretty subtle effect at that point, and thus it’s not really a smash, it’s a bus with a comp.

All clear now? OK, let’s move on to one variation of the technique.

Input Parallel Compression

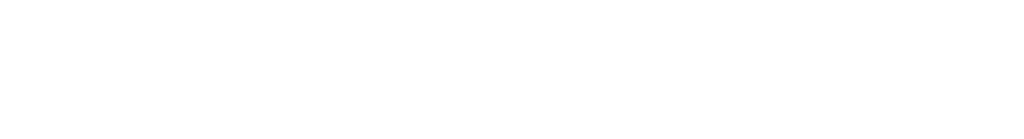

If you only have one channel that you want to enhance with this technique, and you have an extra channel to use, this is a great way to get it done. As mentioned earlier, you simply double patch your mic (let’s say the worship leader’s vocal) into two channels, say 25 & 26.

Channel 25 is your “normal” channel. You may have a comp on it, and you may be doing some mild compression there. You also probably have EQ and other stuff going on; it’s what you normally use.

On Channel 26, you insert a compressor and dial it down so you’re achieving a pretty significant level of gain reduction. How much will depend on the effect you are going for. I’ve played with settings ranging from 4-6 dB of reduction to 12-15 dB. I’ve been using less lately, and been happier with the results.