Once a sound reinforcement system has to project to audiences located more than a 100 to 150 feet or so from the stage, a bank (or banks) of loudspeakers, time-delayed relative to the main loudspeakers, becomes an important tool. (They’re typically called “delay loudspeakers,” “delay towers,” “delay stacks,” and even just “delays” in the pro audio vernacular.)

These loudspeakers, often arrays/clusters, are usually flown via crank towers (or sometimes placed on scaffolding), and are positioned beyond front of house. There can be a single array/cluster flown centrally behind front of house, or if the audience area needing the extra reinforcement is very wide, there can be two (or more) arrays/clusters separated by several dozen feet.

Delay loudspeakers are typically deployed for several reasons:

• Sound pressure levels (SPL) directly in front of the stage generated by the main loudspeakers can be kept at a more reasonable volume rather than “blasting” those located toward the front while delivering additional needed volume to those located toward the rear.

• High frequencies are attenuated by the distance of air, so that at 100-plus feet from the mains, there can be a noticeable loss of brightness.

• There may be obstacles between the mains and the audience, putting some of the listeners in an acoustic shadow.

So, it’s just as easy as sticking some loudspeakers halfway back into the coverage and linking to the left-right outputs of the console, right? Afraid not. While that might work mechanically, it won’t provide the necessary intelligibility without the proper application of time delay processing.

Let’s explore why.

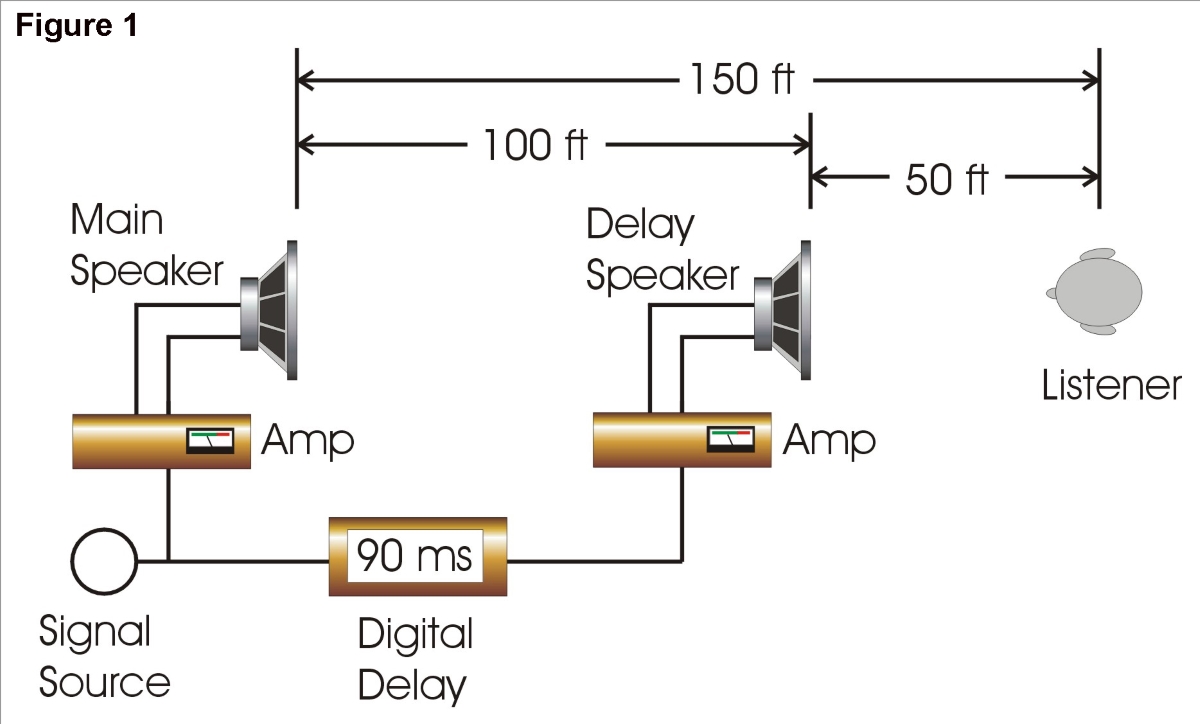

Figure 1 shows two loudspeakers that the audience in the back of the coverage area can hear. For purposes of this demonstration, we’ll place the main loudspeakers near the stage about 150 feet away from our further listeners, while the loudspeakers in the delay bank will be only be 50 feet away.

As a result, sound emanating from the mains needs to travel 150 feet to reach the ears of those further listeners, while the sound emanating from the delays only has to travel 50 feet to arrive at the same place. A little subtraction shows that there’s a difference of 100 feet between the sound paths of the two loudspeaker banks.

Because sound travels at a rate of about 1,132 feet per second while electrical signal travels at something like 1 billion feet per second, there will be close to a 90 millisecond (ms) delay between the two banks — the output from the mains will arrive 90 ms later than the output from the delays.

If no delay processing is utilized, this 90 ms difference will sound like a very distinct echo, with the output of the closer loudspeakers arriving first followed by the output of the mains. This is distracting at best, and at worst, can seriously compromise intelligibility, particularly with spoken or sung vocals.

What’s A Signal To Do?

In order to get the sound from both loudspeakers to arrive at the same time to the intended listeners, we need to add enough delay to the remote loudspeaker so that it “waits” for the sound from the main loudspeaker to catch up. Back in the prehistoric days of audio (before digital processing), various devices such as tape-delay loops and long lengths of coiled plastic hose fitted with horn drivers and microphones were used. These devices were hard to adjust, required maintenance, and/or just plain sounded bad.

With the proliferation of ample DSP in just about every digital mixer, crossover, and even amplifier, keeping a few hundred milliseconds worth of sound in storage is easy. The analog signal is digitized and then sent into storage for a few hundred milliseconds, where it’s then reconstructed into the original analog signal format. This is enough time for the sound in the air to “catch up” with it, and the echo is eliminated.

There are a few consideration when selecting and adjusting delay stacks. First, most quality digital mixers/consoles already have output delays built in, as do many intelligent amplifiers equipped with built-in DSP for crossovers and equalization.

Much of this DSP processing provides down to single millisecond control, and while this may seem crazy at first, I find that even 10 milliseconds of delay is quite noticeable to many listeners. In fact many of my engineering buddies and I regularly tweak loudspeaker crossovers down to the 1 ms level (and sometimes argue over fractions of a millisecond if in the mood).

For fun, we’ve uploaded an audio file on ProSoundWeb, and I encourage you to put on a set of headphones or sit between a pair of stereo loudspeakers and listen to me talking with various delays between the left and right channels. At low amounts of delay (around 10 to 30 ms) it’s merely distracting, but once you get into the 100-plus ms range, you’ll find that the intelligibility goes away fast.

Imagine listening to an entire show or worship service with all of that echo going on and you realize just how important it is to get the delay between loudspeakers set correctly.