Motorized winches. Lift machines. Line shaft winches. Cable drum winches.

Whatever you want to call them, they’re everywhere these days, with more coming.

To ride the wave, however, a lot more understanding has to be brought on board. (Get it? Wave…board?)

Winches that are designed to lift scenery, lighting or other heavy stuff is what we’re talking about.

Please don’t confuse them with machines used for opening and closing curtains on traveler tracks. They are a whole different animal and are not what we are discussing here.

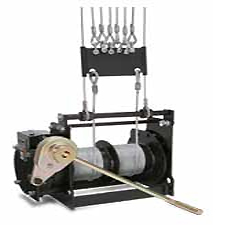

The basic components of a winch are: Electric motor with brake, gearbox (or speed reducer) drum, and control. We’ll take ‘em one at a time.

Electric motors with brakes are simple enough. The motor makes a steel shaft go round and round and the brake stops it.

If your motor does not have a brake then you don’t have a lift machine. (You have either a curtain machine or a boat anchor.) Most motors in our industry have output shafts that run about 1700 RPM.

The important part here is how much muscle they have. Muscle, in this case, is defined as horsepower. More horses, more power.

Now, the gearbox. This is where things can start to get interesting. The gearbox, or speed reducer, is that box-like thing bolted to the motor. Inside there is a shaft connecting the two.

When the shaft comes into the gearbox it is spinning like a bat out of hell. When it leaves it is walking. Maybe something like 30 RPM. It really depends on the desired end result.

And how does the gearbox do this, you ask? Magic? No.

Gearboxes work on a simple principle: different size gears working in conjunction will not only slow down that pesky shaft, but also develop enough muscle (torque) to turn the drum. Different gear configurations get different results. It depends on what the desired result is.

But all gearboxes have two things in common: They all have gears and they all need lubrication. (There’s a joke in there, but I’m not touching it.)

Manufacturers of gearboxes have specifications for lubrication. Buyer beware, however, for these specs are written for industrial users, not us theatre folk. Their specs call for replacing oil after about a zillion hours of use.

In an industrial application this may be once a month. In the theater it could translate to once every ten years. Inaction, as we all should know, can be just as dangerous as action.

If you don’t use that motor very often the oil begins to turn to sludge at the bottom. Less and less oil gets to the gears when you turn it on. Replace your gearbox oil at least once every two years. Check it every year. If it looks dirty, or you see stuff swimming around in it, change it.

Okay, now we move on to drums. Unfortunately, cable drums are not nearly as exciting. (Buddy Rich, now he was exciting.) Cable drums, when lifting heavy stuff over people, (especially when it’s ME down there) must have some common characteristics.

First, they must be grooved. This way the cable will wrap on the drum in a dignified and controlled manner every time. No overwrapping or jumping around.

Second, the drum must be long enough to accept the entire travel distance of the cable on a single layer, including some extra “dead” wraps for safety.

Series winches are designed for continuous duty pulling and their compact design makes it difficult to get cable caught between the drum flange and end support housing.

For example, if you are lifting a piece 20 feet into the air with 3/8-inch cable, the drum must be at least 4 inches long. 20-feet x 3/8-inch cable plus three dead wraps on a 12-inch drum. (At least that’s what Peter Scheu said, and I always believe Peter.)

Third, the drums have to be connected to the gear box. The only right way to attach a drum to a gearbox on a standard lift machine is via direct coupling. (What an image!)

No belt drives, no chain drives, and no flexible couplers – the fewer the parts, the less potential for failure.

Reprinted with thanks to Sapsis Rigging