The call came from Grant Cambridge of Event Enterprises in Cincinnati. The task was to provide sound reinforcement for the Cincinnati Chamber Orchestra for its Summermusik Festival – a collection of unique outdoor chamber music concerts throughout the city of Cincinnati over a period of two weeks with the aim to bring the music to the people.

I quickly agreed yet I hadn’t tackled such a challenge before. I really wanted to get this right – to be respectful of the musicians, helpful to the conductor and present the best experience for the audience. The “festival” was built around six performances. Bookending the series were two shows featuring a 20-plus piece chamber orchestra.

The others were unique combinations of smaller ensembles, including string quartets and a rock band playing Beatles tunes at an amusement park. Another show featured horns and woodwinds at the Cincinnati Zoo. Then there was a jazz organ trio with horns at a beautiful park. The venue acoustics, layouts, tight time frames and environmental noises made for quite a collection of unique challenges.

This article is the first in a series describing my adventure supporting these wonderful musicians. This time I’ll share my approaches to these challenges and the resources I found that helped make this series a success for all. I’ll also note some handy techniques and gear choices.

Speaking The Language

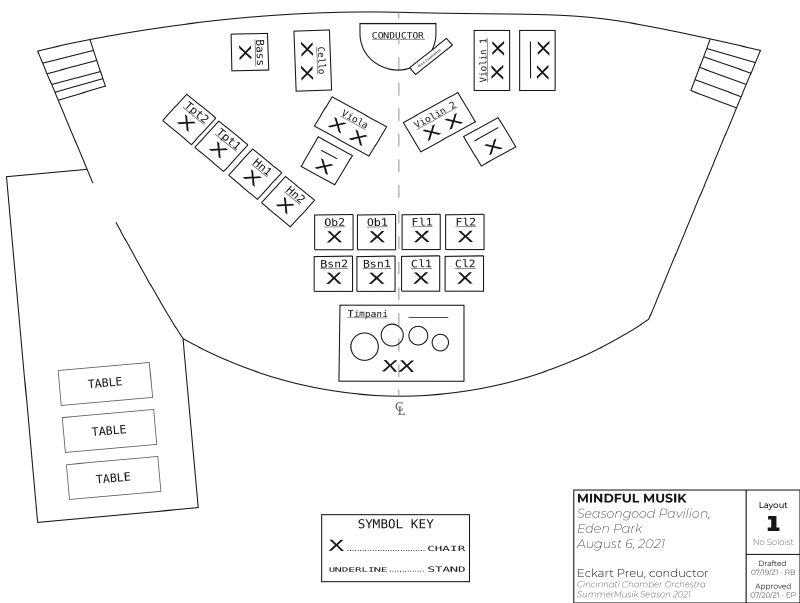

With a bunch of stage plots in hand, things started to become clearer. I was confused by some of the shorthand used to express the number of instruments that make up each show. The terminology used to express sections are like this:

Full concert instrumentation (25): solo cello-2222-2200-tmp-str (4,3,3,2,1)

What This Means: A solo cello, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, trumpets, timpani, four first violins, three second violins, three violas, two celli and one double bass.

Aside from learning how to properly mic a French horn or a woodwind section, I also cared about the etiquette of this world. I wanted to stay out of the way of the musicians and not crowd their respective positions with microphone stands. My goal was to help the musicians feel comfortable and make the sound reinforcement invisible to the audience.

In my search, I came across many resources about orchestral reinforcement and miking in concert halls or recording spaces but not much about taking the concert hall outside in not-so-easy venues, and learning how to tame the challenges of reinforcing orchestral instruments outside for large crowds was essential. Wind, nature and environmental sounds all played a factor.

I was fortunate to come across a great article about reinforcing the Boston Pops with talented engineer Steve Colby (“Sound Reinforcement For the Boston Pops: Miking The Orchestra,” Mix magazine, March 1999) as well as a series of videos by engineer Carsten Kümmel. I knew early on I’d need to also lean on some friends who had more experience with orchestral shows.

My first call was to violinist (and multi-instrumentalist) and friend Paul Patterson, who has been performing with the Cincinnati Symphony since 1985 and is an amazing musician. My goal was to learn about the challenges he’s encountered while performing outdoors without the help acoustically of a concert hall.

Paul mentioned if musicians don’t feel like they are projecting loud enough because they can’t hear themselves as well as in the concert hall, there may be a tendency to play harder resulting in a more harsh or strident tone. This was excellent insight into how to encourage and support the musicians. Taking his advice, I then started reaching out to fellow sound engineers.

Mic Placement & Choices

The common practice with orchestral miking under these conditions is a single mic per music stand/pair of musicians (often two players will share the same music stand, i.e., one mic per pair of violins, etc.). Being aware of bowing direction with string players and where the sound is developing with woodwind and horn players all factor into choosing where to place the mic.

The aforementioned Carsten Kümmel is an exceptional, innovative and experienced orchestral live sound engineer and educator as well as an extremely kind fellow. After devouring his YouTube video series about microphone placement, mixing, desk setup and monitoring, I sent along a quick email with the stage plot for this first large show. He responded with wonderful recommendations on how he would approach such a challenge.

First, he recommends placing microphones and stands out of the way of the musicians. He takes a common-sense approach to strings when outside – two cardioid mics for the first violins, two for the second violins, located above and behind the first chair of each section and pointing to the space in between the two players. With violas, which often are positioned in front of the horns, hypercardioid mics can be used, taking advantage of the 110-degree null or rejection of the capsule to mitigate bleed from the very directional horns.

Carsten has experienced that some mics behave better with wind than others. For example, the Schoeps MK Series are less affected by wind than the Neumann KM Series. Omnis are usually better in wind than cardioids, and the use of an omni pattern is best if no roof is available.

With plots and input lists in hand, Grant and I sat down to put together a game plan for microphones. Admittedly I was throwing the kitchen sink and the bathtub into the first proposed pick list.

For the first large show, I didn’t feel confident using clip-on type mics simply due to the logistics of rigging them to the instruments, plus potential cabling issues and a very tight timeframe. In addition, I wanted to present the warmest sound possible and knew it would be a compromise sonically with the elements we had available.

The Steve Colby article was my stepping off point on how to approach microphone selection. He recommends the venerable Shure SM81 for these important reasons: being outdoor friendly, acceptable wind resistance, capturing a flat response and most importantly, being easily obtainable. So, I stuck with the plan of SM81s nearly everywhere. (I will detail my experience using clip-ons with the rock band and strings later in this series).

Knowing Grant at Event Enterprises had plenty of the mics in his inventory, I made a commitment to use these for consistency and also if we had a failure, backups were readily available.

Leaning In

Recently I hosted a panel of mix engineers for Nathan Lively’s “Live Sound Summit” and reached out to one of the guests, Claudia Engelhart, for some help with my current orchestral challenge. Engelhart is a very talented and seasoned engineer, tour manager, and great human. She stresses the importance of not “over amplifying” acoustic instruments and has found that quieter concerts force the audience to listen more closely and focus. I’ve personally found this is absolutely the case – the audience is leaning into the experience.

The next call was to Ralph LaRocco, a long-time engineer for the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra and Cincinnati Pops who has “done it all” in many very challenging situations. Some key takeaways from Ralph were how to mic a French horn (low and behind the section, several feet back), clarinets benefit from the “floor bounce” from the bell of the instrument and carpeted stages may pose a challenge for the musician.

He also likes to use a few omni microphones for woodwinds and flutes positioned to the right of the principal flute and one to the left of the principal oboe – both at just over the top of their music stands pointed straight up. The bassoon mic should be to the players right, cutting across the player toward the mid/top of the instrument.

The console for this series was a Yamaha CL5. I put all the ensemble in a stereo group, offering a bit of global EQ as well as Yamaha’s wonderful dynamic EQ plugin set to help a bit around 2 to 5 kHz as well as at 125 to 250 Hz. Then I placed the sections (first violins, second violins, celli, horns, etc.) in VCA groups, which gave me the ability to react quickly to suggestions about balances from the assistant conductor.

Soloists were independent of the groups and sent directly to left-right, offering me the ability to easily feature the soloist when necessary by reducing the ensemble a bit with a single fader. In some instances, I employed Yamaha’s Portico 5045 primary source enhancer to help reduce bleed.

Then, to help simulate the concert hall experience, I applied just a touch of a stereo hall effect using a stereo send. I also put a dynamic EQ on the LR. A ground stacked NEXO STM/M28 array was deployed as well as some NEXO PS10s as out fills. No subs were used.

It Becomes Reality

The first show was at Cincinnati’s beautiful Seasongood Pavilion, a unique outdoor amphitheater nestled into a hill surrounded by trees. This show was conducted by Eckart Preu and featured works by George Walker, Tchaikovsky, and Beethoven as well as guest soloist, cellist Sujari Britt.

Time was of the essence – a sound check and full show rehearsal was scheduled within a very tight time frame. I wanted to be prepared and have all the usual patching and routing kinks worked out. The stage plot shows where I chose to place microphones following the guidance of what I’ve learned.

Once the musicians were in place, I quickly introduced myself and took the time to ensure the microphones were placed in a position that was comfortable. I believe this small gesture built trust and instilled a sense that I care about presenting the musicians’ talent and sound with the utmost quality.

The initial challenges with this venue were mainly environmental. Humorously, sound check was accompanied by the unexpected chorus of heavy construction in the area and the constant rumble of dump trucks, a sound engineer’s dream come true. I did my best to rough-in a sound that I was happy with. The assistant conductor and orchestra staff offered tremendous help with balance and sound. Having the score in front of me also helped me anticipate upcoming section features.

After some tweaks with feedback from Eckart (the conductor), we were set. A few hours later, the gates were open and the audience arrived for a beautiful late summer evening under the stars. A brief prelude talk with the conductor and featured soloist came next and then we were set for the show.

I took a few deep breaths and slowly pushed up the VCAs in concert with the first swell of the ensemble. It was magic. The musicians played wonderfully. The audience was kind and everything went as I had planned – no one knew I was even there.

Stay tuned for more in this series. Next time I’ll detail how I managed a string section with a rock band in a very small venue. I hope sharing my experiences here may help you with your next outdoor orchestral adventure.