Microphones

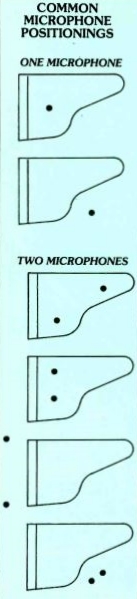

Assuming some amount of elevated importance of the piano part in a song, current use of microphones would most often, these days, require two. Each one addressing what might be loosely described as the bass or treble, corresponding to the left and right-hand regions of the keyboard.

Exact placement, as can be imagined, must be governed by the individual player; that cluster of variables called dynamics. What he is playing, from how soft to how loud.

People like Billy Preston and Elton John are very hard, rhythmic players, and as a result have a strong attack, and a reasonably crisp sound to begin with. Another factor governing mike placement is where on the keyboard he’s playing. Stevie Wonder and David Paich, say, do mostly block playing in the middle region, whereas others like Nicky Hopkins and Keith Emerson are extremely aerobatic, moving all up and down the keyboard.

In any case, dependent on the number of tracks available each mike would almost certainly be assigned to a separate track. The practice of using one stereo microphone has its devotees, yet the criticism of those who have tried and discarded the single stereo mike is that it gives too even a pan, too little left/right separation, too little mixing flexibility.

There is considerable difference of opinion as to what happens when more than two microphones are used on piano. Bob Margouleff has found three microphones wholly unsatisfactory, lending to serious phase cancellation effects and problems in mastering.

Others like Ken Scott regularly use three Neumann condenser mikes, finding it an entirely workable format. When a third mike is added it would more than likely be centered, both in terms of its positioning relative to the two other mikes, and being sent equally to both tracks on the tape. A third mike can, and is most often used to fill in the hole that often appears in the center of a wide stereo perspective, or for ambience or texture if placed more distantly.

Four mikes are occasionally used, in which case they would more than likely be approached as two fairly symmetrical pairs, say, a close left and right augmented by a distant left and right. Tom Perry has used two up above the hammers, and two in the back. He considers that it worked for that particular tune. “It was okay – it wasn’t startling.”

Microphone Placement

There are a number of basic regions from which the piano can be miked. It is most often miked from above. One mike generally goes right over the middle. The sound holes are occasionally used. There are usually three but on some models a number of smaller ones as well, function to help the piano sound project. Occasionally they prove effective for keying mike placement.

Mikes have been placed around and sometimes in the sound holes (usually one mike over the middle hole in the mono days) but in recent times most people have had little luck with this placement except where the emphasis from this very localized pickup of selected notes (strings) is the objective.

In short, microphone placement in, or close to any of the holes produces uneven level and tone, selecting for the notes and frequencies directly beneath them, perhaps masking what is coming from the rest of the keyboard.

Also, the sound in general is said to be constricted. Mack says, “The effect is not marvelous. Still it does work in cases where the player is playing right under the hole or holes being miked, and you want that kind of constricted sound.”

The piano is often miked from any number of points around the periphery, lending a looser, funkier, roomier, old-timey kind of sound. The most common location is probably off to the right, near the middle of the curve to capture the sound deflected by the lid.

Mack used peripheral miking for some of the piano overdubs on the new E.L.O. album, with a Neumann KM -84 set to cardioid behind the player, and a tube style U -47 set to omni, three feet beyond the back of the piano, both mikes six feet off the ground. Rarely is a piano miked from below, and when so, almost always for greater piano isolation.

The normal range of close-miking seems to be from 8 to 30 inches from the strings. Closer than 8 inches can produce undesirable components; uneven dynamics (the notes closest to the mike being too loud), uneven perspective (too exaggerated), and unwanted content. A piano too close-miked might reveal too much hammer sound as well as curious ringing, mushiness, wooliness. In conditions of complete or nearly complete isolation, the acoustic piano can be fairly distantly miked.

According to Andy Johns the piano on the Rolling Stones’ “Moonlight Mile” was in a completely empty room at Stargroves, having a wooden floor and plaster ceiling and walls, and miked with one U-87 four or five feet directly above the piano. The lid was completely off. John Sandlin (the Allman Brothers, Bonnie Bramlett, Cowboy) often mikes Capricorn’s nine foot Steinway (once the resident piano at Carnegie Hall) from 10 feet away on overdubs.

Limiting

Limiting/compression was used tor a time on the piano – particularly in England – but is not used that much any more. An integral part of the “English” piano sound, it lends what Jimmy Miller refers to as a “grindy” sound, as opposed to the “pure” or “open” sound. The Audio & Design and Neve limiters are reported to be excellent on piano, as are the UREI LA- 2A’s, LA -3A’s, and 1176’s.

Equalization

Having such a full tonal range, the piano responds well to equalization. Boosting under 100 Hz. can, as with most instruments, bring up rumble. And likewise, boosting above, say, 12 kHz. can emphasize what are probably unwanted overtones and cymbal leakage. Interestingly, a piano may be made to sound somewhat like a tack piano by cutting in the 1.5 to 3.5 kHz. region, which seems to remove the “fullness” or “body” of the notes, thus emphasizing the attack and leaving that “hollow”‘ sound.

Stereo Piano

Stereo piano emerged – quite incidentally, though – in the late 50’s or early 60’s. It was because some consoles back then didn’t have a center bus, and so the best way to center the piano was to use two mikes and bring one up left and one right.

The Doors did stereo piano on “Yes, the River Knows” (July 1968), but the institution of Stereo Piano didn’t really begin until the 16-track era. Stereo piano nowadays is probably the norm. It is usually medium-spread, and, in instances where piano is the song’s main instrument and/or it’s a record by a featured artist who plays piano, often given a full spread.

Editor’s Note: This is a series of articles from Recording Engineer/Producer (RE/P) magazine, which began publishing in 1970 under the direction of Publisher/Editor Martin Gallay. After a great run, RE/P ceased publishing in the early 1990s, yet its content is still much revered in the professional audio community. RE/P also published the first issues of Live Sound International magazine as a quarterly supplement, beginning in the late 1980s, and LSI has grown to a monthly publication that continues to thrive to this day.