Tuning

Obviously, the sound of a piano will depend on its tuning as well as any individual treatment or adjustment it may have undergone. The practice of tuning sharp – anywhere between 441 and 444 (the European middle “A “) is still very much in evidence.

Still quite valid is the paragraph relative to tuning from the article appearing in R-e/p during 1971 (Recording The Piano – A Forum, Vol. 2., No. 2, March /April 1971, pages 11-17).* “… the reason for tuning sharp is to get the whole band changing … nobody could lay back, or they would get lost.”

“While there is quite a bit of sharp tuning on straight-ahead band sessions, the technique just doesn’t work at all well when sharp piano is played against electronic instruments which cannot change intonation to get up with a sharp piano, or sharp strings.”

The brightness of a given piano can be adjusted by a tuner manipulating the pins embedded in the hammers. Pulling them out more will add more attack and brightness, pushing them in will do just the opposite. However, regardless of specific make or tuning the piano is a true binaural instrument, a large instrument with the sound emanating from a broad surface area.

The instrument produces what might be seen as three essential types of sounds. First, of course, are the actual musical tones. The piano has a fabulous frequency range, from about 27.5 Hz. to 4,096 Hz. for the root notes, with the (usable) harmonics going up to about 12 kHz.

Secondly, there are the percussive or mechanical noises attendant to producing the musical sounds – the actual sounds of the hammers hitting across the strings, and when the piano is miked from the player’s side of the keyboard, the sounds of the keys hitting the wood.

Lastly, the piano emits considerable unwanted and extraneous information consisting of both low tones and high harmonics. These factors help explain why it is oftentimes claimed that piano is an instrument difficult to get into perspective compared to others. So, inasmuch as there are the usual different notions of just what a well-recorded piano should sound like it seems that only one criterion meets with any sort of general acceptance.

Consistency is certainly that order; where no notes either jump-out or get lost because of difference in tone or level. Ideally, it is agreed to by most that the instrument should sound smooth and even, from octave to octave, across the keyboard. Likewise, very few go for a particular occasional aberration in such perspective where one or more treble notes seem to be coming from the bass region, or vice- versa.

Beyond consistency, there is some temptation to further generalize that clear articulation of notes is a minimum requirement. But, no, there seem to be many who eschew close miking, opting for the more distant, open, airy, and “fuzzier” sound.

Placement And Isolation

The grand piano, because it is a large acoustic instrument, and particularly when it is not recorded using very close miking, tends to pickup considerable leakage from other instruments. In the great majority of cases this is considered a problem, but every once in a while that very same leakage can be an asset, and the instrument wants to be positioned out in the recording environment to take advantage of its sonic magnetism.

With this in mind it might do, now, to look at several of the techniques used by various studios to position the piano. Among the most sophisticated means for isolation are the completely separate, trapped, piano rooms installed at many studios.

At Caribou they have built an acoustically-lined piano cutout in the studio wall, which yields the dual advantages of absorbing almost all of the piano sound, at the same time keeping the instrument and its player in the same environment as the other players. At Caribou the microphones are hooked onto the ceiling of the cutout. Elton John’s “Rock of the Westies” LP was cut at Caribou as an example of how the cutout sounds.

Another sophisticated approach to isolating the piano in the center of the recording environment is the piano box Gus Dudgeon had built for Elton John. The box was built to match the piano’s configuration, 4 feet tall. The interior is damped with fiberglass, all except the ceiling of it which is left untreated and is a reflective surface.

Using this box, Gus has five feet (including the 12 inches from the top of the piano down to the strings inside the piano) to work with for his piano sound. In this way, he has found it possible to get away from the unwanted sounds too close to the strings, without any loss of isolation. The sound Gus gets for Elton is described as a fairly distant, binaural, but clear piano sound.

By far the most commonly used tools for controlling the piano’s sound is the combination of position in the studio, the position of the grand piano’s adjustable lid, as well as the use of a variety of damping materials such as furniture blankets and other draperies. Essentially, how the lid and /or damping materials are arranged, in other words, how the piano is allowed to breathe, determines its ambience.

Those who like the lid down often refer to a “tighter sound,” “better isolation” and a “stronger bottom end.” Those devotees of the open lid are heard to criticize the “too confined sound,” “a lot of

unwanted mechanical noises,” not the least of which being bottom build-up … boomyness.

Admittedly, a consistent problem for the up-lid-ers is that of the piano player singing a live vocal. Among those who do away with the lid completely is Bob Margouleff who prefers to record piano completely unfettered, and the only instrument in the main room.

Arranging The Piano

As we have seen the acoustic piano is an extremely expressive and versatile instrument. From a recording standpoint, after guitar, it is probably the instrument most represented on American and English pop music records of the last twenty years.

The piano is extremely melodic – much more so than rhythmic – it lends itself easily to orchestration, and all things considered is probably the instrument most closely associated with modern-day English language pop songwriting.

From an arranging standpoint, the acoustic piano can do just about anything and can therefore be used just about everywhere. As a song’s featured instrument, as color, just trimming, as a texture, solo … name it. The essential clue to its versatility is of course its huge range, extending 11 octaves from A, 39 notes below middle C to C, 48 notes above middle C.

Each hand can play five or even more notes at once (though few players go higher than eight, total) and anything from single notes through fragments and into complex chords. Then, too, the piano can be played several ways although almost everyone plays it from behind the keyboard, depressing the keys with fingers, generating a traditional range of sounds.

However, there are people, a good example would be Jim Price and the Doors, who have other ideas. It can be used in such a way as to sound like a cymbalon, by merely going back to the strings and plucking them with one’s fingers, which is what Jim Price did for the intro of the Rolling Stones’ “Moonlight Mile.”

Or, you can do, in the words of Bobby Krieger, “inside the piano strings fooling around,” as the Doors did on their avante garde piece “Horse Laditudes.” These aberrations aside, piano is a large instrument, and in most cases sounds like it.

Most piano parts contribute a fair amount of notes, a lot of mass, and a lot of oomph to a song, meaning that it also has the potential to contribute considerable confusion as well. The solidness of the instrument plus the fact that he’s undoubtedly playing a considerably greater number of notes than anybody else, probably in that same (middle) tonal range as most of the other instruments, makes it easy for the piano to simply wash-out the entire recording to a point where it is virtually impossible to hear what is going on.

Additionally, there is the anomaly to contend with of the acoustic piano and the electric guitar, for some reason, can just naturally antagonize each other. So, controlling the piano as a function of its size relative to the production at hand, as can be seen, is the job of both the arranger and the engineer.

Simply stated, the piano can be described as either little or big. It’s size most usually is a direct reflection of its importance to the song; if it is just trimming it would probably be small and would be taken mono for the mix; fairly important and it would be larger (very likely stereo); and if it were the featured instrument it might very well be recorded for large-spread stereo.

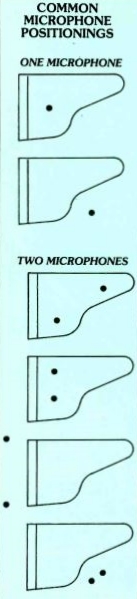

Not unlike other instruments, you’d record, a small piano would have at least some of the following characteristics: one mike, close-miked, limited, rolled-off bottom/boosted top, mono, little level and echo in the mix.

By contrast, a big piano would have among the following: multi-miked, close and distance miking, boosted lows, mids and highs, stereo, big spread, lots of level and echo in the mix.