From the December 1977 issue of Recording Engineer/Producer (RE/P) magazine…

The piano that one hears with one’s ears is so difficult to capture on tape that many engineers have yet to record it to their own satisfaction. Engineer Tom Perry (Boz Scaggs, Helen Reddy, Dean Martin, Glen Campbell, Crackin’) among them, calls it, “personally the most frustrating instrument” to record.

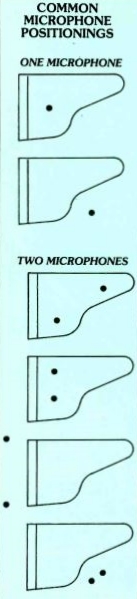

“I’ve tried everything from … I’ve tried every microphone in the world on a piano … I’ve tried a different number of mikes, different positions – underneath, above – lid completely off – mikes high, mikes low, mikes on the bridge, mikes on the sounding board, mikes in the back of the strings, three mikes, four mikes, two mikes, one …” Many confess to an uncertain relationship in general with the instrument.

Perry again: “I don’t know if it’s just me or what, but for some reason I’m never particularly happy. I don’t know what I even want to hear . . . somehow it never seems to sound like when you’re just standing next to a piano.”

Perhaps its elusiveness in even being photographed (much less painted) on tape can account for why there is not a whole lot of fooling around with the sound of the acoustic grand piano among the more mature engineers.

Mack Munich (David Bowie, the Electric Light Orchestra, Led Zeppelin, the Rolling Stones, Donna Summer) is one who typifies this position. After having taken considerable liberties with the instrument during his experimental phase he has come to eschew what he calls the bent or heavily processed piano sound. He describes the natural sound he likes as “bright, hard and clear,” a good example being the Electric Light Orchestra’s “A New World Record” album.

Bob Margouleff (Stevie Wonder, Billy Preston, Minnie Ripperton, Lothar and the Hand People) describes the natural piano sound he wants to hear as a “full-bodied piano sound with a lot of bottom, stereo, a big spread. A natural sound.”

However, unnatural piano sounds which have contributed to hit records have to be acknowledged as well. Among the best examples which come to mind are those by the Beatles who have probably done more with the piano sound than anyone else. “Sexy Sadie,” “Birthday,” and John Lennon’s “Imagine.” With the preceding as an introduction it would seem to be constructive to take a look at several components of the problem as an aid to possible individual solutions.

The Piano

To the best of everyone’s knowledge, the first piano was built around 1709 by Bartholomew Cristofori of Florence, Italy. Most of the instruments, as we know them today, have 88 keys, each of which, when depressed, activates a felt-tipped hammer which in turn strikes from one to three unison-tuned strings, producing a note.

The piano also has dampers – small rectangular pieces of wood whose undersides are covered with felt – which modify the sound by moving closer to, or father away from the strings. The dampers are controlled by three independent foot pedals: the left (speaking from the player’s point of view. His left hand is left, his right hand is right) or soft pedal, which shifts the entire harp to the right so that the hammers hit one less string per key.

The middle pedal, called “sostenuto” or sustaining, when engaged takes the damper off whatever keys are depressed, sustaining that chord. The right pedal, known as the damper or sustain pedal, takes the dampers off all of the strings, not only sustaining whatever notes were last played, but also letting all the other strings vibrate sympathetically. The whole instrument is sustaining, in other words. Two or more pedals used simultaneously produce a more or less cumulative effect.

There are two main physical permutations of the acoustic piano. First and foremost there is the grand piano, it being the form used for the majority of piano recordings. The grand piano extends horizontally and measures anywhere from 5 to 9 feet long, the smaller ones being called baby grands and longer ones concert grands.

Generally speaking, (for less than piano virtuoso solo recordings) the optimum size for contemporary recording purpose is said to be a 6 to 7 1/2 foot grand. Beneath 6 feet the sound tends to be described as too boxy, too contained, and beyond 7 1/2 feet the sound becomes too rich in harmonics, sometimes referred to as being ringy. The smaller, box shaped upright piano is typified by foreshortened strings anchored to a vertical harp, and is about 2 feet long.

Brand And Sound

The difference in sound among the various brands of grand pianos are as a rule fairly subtle. They are pretty much all going for a similar purity of the tone. The main difference is really in the touch.

Still, according to comment, there are identifiable subtleties: Steinway & Sons is very much the standard, and is known for its uniformity of tone across the keyboard, full but not-too-rich sound, and percussive qualities. Those are Steinways on the Beatles’ “You Like Me Too Much,” John Lennon’s “Imagine,” the Allman Brothers’ “Jessica,” and the Rolling Stones’ “Melody.”

Yamaha has lately become very popular for studio use, and is considered to be among the brightest sounding. That’s Musicland’s (Munich) 6 foot Yamaha grand on the Stones’ “Hot Stuff” and “Memory Hotel.”

Baldwin has recently shown an increase in popularity as well. The instrument is known for its heavy action and full, “big” sound. Mason-Hamlin is perhaps the loudest and richest of the lot, and is known also for its heavy action. Neil Diamond swears by them.

The Bluthner grand is celebrated for its uniformity, a sound that is clear and strong at both top and bottom, as well as for its light action. That’s a Bluthner that Paul McCartney is playing at the Twickenham Sound Stage for the “Let It Be” album.

Bechstein is a loud, bright, and percussive piano, and finds great favor with classical people. Trident Studios’ Bechstein is heard on Elton John’s “Your Song” and “Take Me To The Pilot,” and Queen’s “Dear Friends.” The Bosendorfer grand has 92 keys and is know for its amazing action and mellow sound. Al Stewart’s “Year of the Cat” cut features a Bosendorfer.