I’d like to begin by describing a typical day, but in my experience, there’s no such thing. That’s one reason why I love the freelance life. I’ve been working in pro audio for over 30 years, the last 20-plus as a freelancer in the Orlando area.

I do everything from small breakouts to large general sessions. The small breakouts are usually an analog mixer with 12 or 16 channels,and a handful of wireless microphone systems, both handheld and lavalier. I’m responsible for my own frequency coordination in small meetings, so I carry a network switch and several ethernet cables in my kit.

I also have my personal laptop with me, which has the Shure Wireless Workbench (WW) spectrum management platform installed. Most of the time, the wireless equipment provided by the rental company have the Shure brand, which means easy deployment with WW.

Backup frequencies are often necessary because invariably, someone in an adjoining room will turn on a wireless unit after I’ve done my scan and deployment, causing noise and interference. With help from WW, changing a frequency is fast and simple, especially with their line that changes the frequency in both the receiver and transmitter.

Otherwise, the software will deploy a new frequency to the receiver and I have to physically sync the mic. Still, it’s better than having to rescan and reassign. WW also allows me to monitor the wireless hardware in real time.

Foreign Concept

Call time is typically 8 am, which means the unofficial arrival time is 7:30. In this business, early is on time, and on time is late. It also means I leave my house no later than 7, and sometimes, at 6:30. (I’ve also had calls as early as 5:30 am.)

I reside in north Orlando and the convention hotels are on the south side or on Disney properties in Kissimmee. Rush hour in the city is well under way at 6:30 am, and since roughly 140 people move to the area every day, traffic gets worse by the day.

Most days I find out what equipment I’ll be working with when I arrive onsite. Pre-production and advance communication seem to be a foreign concept. The one big exception is when I’m working with production company LMG. Their system sends me a link to a technician portal where I can view all of the equipment that will be arriving on site… hopefully. (I frequently find myself in a holding pattern while waiting on something to arrive that was supposed to be on the truck.)

Nevertheless, at least I know what equipment I’ll be working with in advance, which gives me a rough idea about the size of the meeting. I even know who is on the crew, so if I see a show caller on the crew list, I immediately know that this is a bit more than a small breakout. I also know whether it’s a breakout or a general session and can plan accordingly.

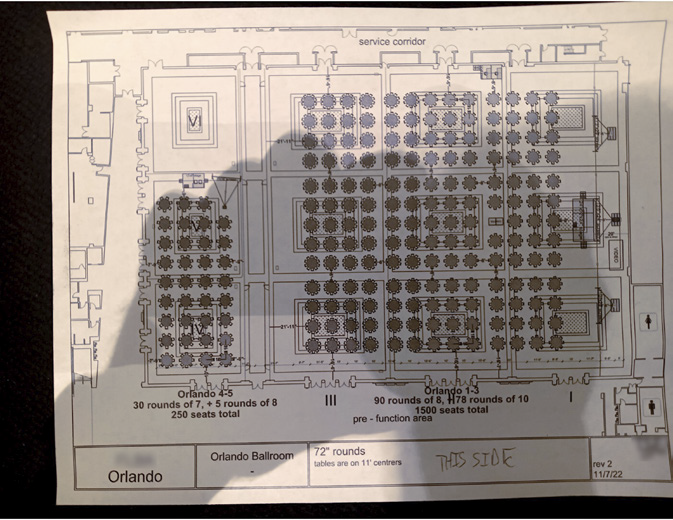

First, I check who will be serving as the A-2 on the project. I admit to having favorites,and always hope to see one name in particular. Another item I look at is the room layout. Again, LMG is the only provider that gives me access to it in advance. Otherwise, I look at it upon arrival.

I need to know where I’m gonna place equipment, where front of house is located, and plan cable runs – it frequently involves riding cable on a truss. Further, I need to know where to put “audio world” and where the audio power drop will be located. Sometimes I’m looking at the room layout with the A-2 and we’re discussing what goes where as well as some of the details of the show involving audio. Otherwise, I get with the A-2 after I’ve reviewed the layout.

For larger gigs, we begin, of course, with a brief meeting with the producer and the crew leads to get any last-minute updates and a safety reminder. Everyone knows someone who has been injured on the job, and we all take safety very seriously. Most of us are freelancers, and if we can’t work, the money stops coming in. We know what’s at stake.

After this brief meeting, we unload the trucks at the loading dock. This is another reason why I look at the room layout when I arrive, because I need to direct the stagehands as they roll in the road cases with audio gear. Depending on the size of the show, this takes anywhere from a couple of hours to a couple of days.

After the trucks are unloaded, the lighting crew begins assembling the truss on the floor per the room diagram. Moving road cases around after the truss is assembled on the floor can sometimes be a challenge, which is why we try to have the gear in its approximate location first.

The riggers are busy connecting motors to the pick points up top and to the trusses on the floor. The lighting crew is busy moving lights into their position, and they’ll hang them on the truss after rigging raises the trusses to working height (about chest high off the floor).

Sometimes loudspeakers will share a truss with lighting; other times loudspeakers will have their own truss or single pick points. In the case of line arrays, the angles have been calculated in advance (usually by a system tech) and we work closely with a rigger to hang them. However, on occasion, we’ve put line arrays on scaffolding with very little or no tilt on each box.

Hopefully, the hotel staff has put the staging in place before all this begins, and the carpentry crew is busy assembling and placing the scenic elements while the video crew is building and placing the projection screens, video walls, cameras, and projectors. The audio crew will be putting the front fill loudspeakers and cables in place on the front of the stage.

High Priority

There are numerous things to do for audio, all of which the A-1 is ultimately responsible for. High on the priority list is frequency coordination for wireless microphone systems. (I’ve yet to deploy wireless in-ear monitors on a corporate gig.) Sometimes there are several breakout rooms in close proximity, each one using several wireless frequencies, so a dedicated frequency coordinator with specialized equipment is needed.

The coordinator furnishes a list of frequencies for each room and we tune the equipment manually using those frequencies. If I see a lot of interference on any of the frequencies that I’ve been assigned, I contact the coordinator who will provide another frequency to use. It’s vital for the coordinator to know what frequencies are being used in what rooms. Otherwise, frequency coordination will be done by the A-2 or A-1, and we typically use Wireless Workbench for scanning and deployment.

Another thing on our list for general sessions and large breakouts is the intercom (“com”) system that allows the show crew to communicate with each other during the event. This is always the responsibility of the A-2, who must be knowledgeable about the system being deployed whether it’s a hard-wired RTS model or a wireless digital wireless platform such as a Clear-Com FreeSpeak II.

Further, the A-2 must know how to split the com system so that each department can have two channels – one for production (everyone on the com system can hear and communicate), and another channel specifically for that department. For example, the A-2 might have a question for the A-1 or vice-versa. The production channel doesn’t need to be cluttered with traffic that only applies to audio, so we would use the dedicated audio channel. Additionally, the A-2 has to understand how to connect the hardwired system to the wireless system.

While the A-2 is busy with all that, I’m connecting things at front of house and then building a show file on my digital mixer. I prefer to build the show file in advance on my home desktop computer using the offline editor, but since advance communication is so scarce, it usually doesn’t happen that way and it’s not limited to corporate events – every engineer who mixes for bands, festivals, clubs and the like bemoans the lack of advance communication. If they’re fortunate enough to get a rider, it’s often outdated and inaccurate.

The consoles that I see most often these days on the larger corporate gigs are Yamaha CL or QL Series. On the smaller gigs, I see Behringer/Midas X/M 32 mixers, and in the small breakouts, there are often Mackie analog boards or one of the company’s digital DL Series that has no control surface. (Control is via an iPad using the Master Fader app.) I’ve also seen small QSC TouchMix mixers, which I find very impressive for its size.

Depending on the size of the event, I’ll have several different sends going out from my console, one of which, of course, will be the subs. Yes, I like to use aux sends for my subs instead of crossovers, but that’s just me. I program the crossovers internally in the digital mixer, so I send only the low frequencies to the sub outputs.

I also have sends going to the BSMs (backstage monitors), frontfills, green room, foyer, recording decks, delay loudspeakers, floor wedges, internet feed, and, of course, the main loudspeakers, typically using a combination of aux sends and matrices will pretty much always be post fader.

In addition, I have an aux send dedicated to recording the show announcements and voiceovers (“I.R.’s”) on site to my laptop via a USB interface, which I carry in my kit. Very rarely do I have to apply any post-processing to the recording, but I do have to separate them, tag them with some type of unique identifier, such as “Stewart Intro,” and then line them up in my playback software to play them on cue when the show caller calls for them on the com system. This has to be done on site as quickly as possible, but it must be done accurately.

My playback software of choice is Sports Sounds Pro, although I advise against using the free version because it’s so limited. I once forgot to purchase the full version for a new laptop, and when the show caller called for a cue, the software wouldn’t play it, causing me to miss a cue. This doesn’t go over well at all in a corporate event – miss enough cues and you’ll get fired on the spot with another A-1 already on the way to replace you. (I’ve seen it happen.)

Lastly, I always have a mic for myself at that console that goes out to all of the feeds, in case I have to make an emergency announcement and ask everyone leave the building. I’ve never had to use it, but it’s always available.

Making It Optimum

When it comes to tuning the equipment to the room, I’m old school. All the digital consoles have oscillators for generating pink noise, which I use with a real-time analyzer (RTA). I can ring out a room if necessary. One of the features I like about the Behringer/Midas X/M32 console platform is the ability to route the reference mic input to the on-board RTA. And I must admit that there is a certain paradox in referring to myself as old school while using a modern digital mixer.

After everything is in place and connected, I run low-level pink noise just to make sure I have signal going to all the loudspeakers. The trusses are still at working height just in case I need to troubleshoot a loudspeaker that’s not working.

Once that’s done, the trusses can be raised to trim when lighting, video, and scenic are ready as well. (Scenic is most often on a separate truss configuration.) If the loudspeakers are using their own pick points, separate from the trusses, they can be raised independently.

After the loudspeakers are “flown,” I begin tuning the system to the room with pink noise. I prefer to do this during a time when everyone else has left the room, but if that’s not possible, I announce over the system that pink noise will commence in 10 minutes, then five minutes, then one minute. The reason I do that is because it will be difficult if not impossible to hold a conversation while I’m running pink noise, and anyone who doesn’t want to be in the room when it happens has time to leave.

When it comes to predictive software such as Meyer Sound MAPP 3D and L-Acoustics Soundvision, I prefer to leave it to the system tech – especially if we need to calculate the angles of line arrays. We work together so we know precisely how the system is designed and what must be done when we arrive on site… assuming we have information in advance.

Speaking of working together, a capable and experienced A-2 is worth their weight in gold. They’ll handle the wireless coordination, placing lavalier mics on presenters, connecting and routing Dante in accordance with the design of the system and my patching scheme (which we’ve talked about in advance) and overseeing the connection and programming of the com system, as well as placing and connecting the BSMs. Experienced stagehands can make all this a lot smoother.

I also work much smaller events, of course, which is typically a couple of point source loudspeakers on stands, sometimes with delays, and maybe a couple of subwoofers. There’s no A-2 or system tech, and there may or may not be someone to coordinate wireless frequencies.

I don’t remember doing one of these events with hardwired microphones other than at the lecturn, and I’ve had as many as a dozen wireless frequencies with a handheld and a lavalier mic tuned to each frequency. You can’t use both at the same time on a frequency, so in order for me to keep track of what’s available and what’s not, I place microphones in separate locations.

For example, if a handheld is deployed on a particular frequency, I move the corresponding lavalier to my designated “not available” space. When the handheld is returned, both mics go back to my designated “available for use” space. That way, I can see at a glance what’s still available and I won’t inadvertently reach for a handheld when there’s already a lavalier in use on that frequency, or vice versa.

One issue that pops up every time on the smaller setups is whether to run stereo or mono. When a mono configuration is used, there’s only one cable “home run” from the mixer or the snake to the first main loudspeaker, which is then daisy-chained to the second main loudspeaker. It’s faster and more convenient than two home runs for stereo, but it eliminates the ability to pan left or right, and inevitably there’s always one presenter who, without warning, will walk offstage in front of a loudspeaker with a live microphone.

Or, there are Q&A microphones and someone who is seated directly in front of a main loudspeaker wants to ask a question. If I’m running a stereo configuration, I can simply pan off a loudspeaker in order to avoid feedback, but in a mono configuration, I have to kill the entire system, which results in everyone looking at me, thinking I’ve done something wrong, which makes the client very unhappy.

Unhappy clients can affect my livelihood, so I always run stereo but with mono signals, so that both sides of the room get the same audio. In order to get a stereo effect, one would have to be equidistant from the left and right loudspeakers, and that’s not possible for everyone in a live event situation. I’m well aware of the rare exceptions, such as the sound of a horse or a race car or thunder going from one side to the other.

What’s In My Kit

My kit has evolved over the years, and it looks very different these days from the one I outlined here. I now carry a large, heavy kit on a small, folding hand truck. The case is roughly twice as deep as the typical Pelican 1510 case, it costs about a tenth as much, and is very sturdy.

On the other hand, it doesn’t come with a lifetime guarantee. I can’t fly with it, but since I live where the work comes to me, flying with it isn’t an issue. I could offer a detailed list of what’s in my kit, but that’s beyond the scope of this article.

I will say that the reason it’s so big is because I never know what I’m walking in to, so I have to be prepared for just about any scenario. I’m usually hired by a labor coordinator who has no information at all regarding the size of the event, the equipment I’ll be working with, or anything else beyond the location and call time. Aside from the aforementioned LMG system, getting information that will help me prepare is usually an exercise in futility, so my kit has to be stocked accordingly and it goes with me on every gig, whether it’s a small breakout or a large general session. Some of the items include an eight-port network switch, an electrical multimeter, Behringer UMC22 USB interface reference mic, three folding tabletop mic stands, several Ethernet cables, adapters of various types, headphones, couple of direct inputs for computers and cell phones, some AA batteries, a first-aid kit, and tape – board label, electrical and black gaff.

Also onboard are tools such as the ubiquitous crescent wrench (“C-wrench”), screwdrivers, multitool, laser distance finder (“disto”), a cable tester, and an electrical outlet tester, speaking of which – I once tested every house receptacle in a meeting room of a nationwide chain convention hotel and discovered that not a single receptacle was grounded! During an event, I use power drops, of course, but if I need to test something before the drops are available, I use the house receptacles… that is, unless I discover that they’re not grounded!

Probably half of what I do is troubleshooting, and it’s usually something simple, such as trying to find out why an electrical cable doesn’t have power or why a particular speaker doesn’t have a signal. It’s happened more than once that I’ll trace a cable and discover that it’s not connected to anything because someone failed to complete the run. Or perhaps I’ll find a flaw in my patching. Once in a while, it’s just because I forgot to bring up the master fader.

Appearances Matter

Another aspect of being an A-1 for corporate events is standards in appearance and conduct. I don’t smoke, but those who do must be careful to avoid smelling like an ash tray. Likewise, I’m not a heavy drinker, but those who are must never ever show up with alcohol or their breath or their clothing.

It may be difficult to believe, but I’ve never been high or drunk in my entire life. Make no mistake – no one enjoys popping a cold one after a long day of loading in/out or sitting behind the console, but I’m a one-and-done guy. I enjoy a glass of wine with dinner, perhaps, but alcohol in excess is just something I’ve never been interested in. Tattoos must be concealed. (I don’t have any of those, either.)

The uniform of the day for load-in, load-out, set, and strike is black cargo pants, a black T-shirt or golf shirt with no logo, and comfortable black sneakers or other type of work shoe. During the event, it’s black dress slacks, dress black shoes, a black golf shirt (sometimes a dress button-down long-sleeve black shirt), and a black jacket. It’s a corporate business environment, and the rules are quite different from, say, an outdoor festival or rock concert.

A high standard in conduct also has to be maintained in the corporate event world. I’m not one to use profanity in my daily life, so it’s not something I have to be conscious of when I’m working, but others must always keep in mind that the client might be standing right next to them without their being aware of it as they rail against the company he/she works for or the people he/she works with, using colorful descriptions or complaints. That will also get you quickly dismissed from the job.

Generally speaking, I don’t have any direct communication with the client. That’s the producer’s job, and if I have any questions or issues, I communicate with the producer. It’s best to avoid speaking to the client unless I’m spoken to. That’s the unwritten rule in the corporate event world.

The exception, of course, is when I’m placing a lavalier mic on a client or a client’s presenter, but even then there’s a certain professional decorum that must be maintained. They’re not my buddy, and we don’t trade jokes or personal details. When it comes time for me to retrieve said mic after the presentation, the presenter is often surrounded by audience members who are asking questions, discussing certain points, etc. I avoid interrupting those conversations, instead standing a comfortable distance away, and when the presenter sees me, they position themselves in a way that gives me physical access to the mic, which I retrieve silently, then walk away.

Every audio engineer has their own way of doing certain things, different approaches, different ways of conceptualizing, and different personality traits. The wise among us understand that there are things we can all learn from each other.

I’ve met other engineers who, not even having been asked a question, immediately launch into some complex mathematical formula for calculating resonances as they relate to the size of a sound wave at various frequencies and how variations in the room temperature, construction material, and architectural shapes will affect said sound waves, depending on whether the room is full or empty, yada yada yada.

What I hear in those instances, is, “I’m a audio engineer who is insecure and not confident in my abilities, so I must impress you with what knowledge I do have.” So yes, you can consider me impressed. Now let’s get to work.

Welcome to my world, where there’s high pressure, plenty of responsibility, lots of frustration, and zero room for error, but lots of variety, job satisfaction, and a high sense of accomplishment. The pay is pretty decent, too.

Editor’s Note: Special thanks to the author for also providing the photos appearing with this article.