When I was growing up, my mother would stand me up against the frame of my closet door and mark my height on the wood. This chart of my growth during the first dozen years of my life is still there.

Nowadays, I’m not sure my mom could reach high enough to mark my adult height, but what’s strange is that I don’t really remember getting any taller. In my mind’s eye, I’ve always been the same height, and things around me just got smaller.

Since we always experience things from our own perspective, we’re maybe not the best judges or our own changes, especially when that change is gradual. (“When did I go gray? When did I get fat? Is that really what my voice sounds like?”) My closet doorframe was a “yardstick” of reality, an objective record of what really happened, not tainted by my own perception.

Filling The Gaps

I jumped into my first touring gig as an FOH engineer with the typical young-gun hot-shot attitude that comes as standard issue for fresh college graduates. During the tour, I mixed with a couple dozen different consoles, from Profiles to powered mixers, in venues ranging in size from 35 to 3,500.

I also mixed on line arrays for the first time, and had to solder one venue’s decrepit rig back together in order to limp through a show. In other words, I got my butt kicked in the best possible way. As the saying goes, “Experience is something you get just after you need it.”

Upon returning home, I thought, “Wow, OK. So there’s a lot more to this that I didn’t know about.” I logged on to Amazon and depleted my (meager) checking account on as many audio (and related) books as I could, and when they arrived, I devoured them.

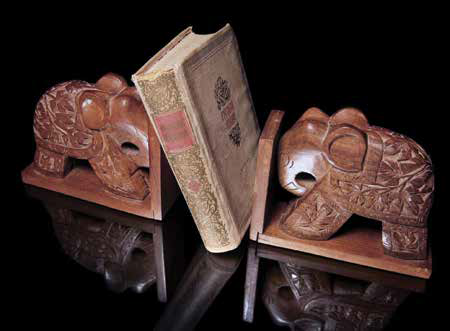

I learned acoustics from F. Alton Everest, psychoacoustics from Floyd E. Toole, the principles of rigging from Harry Donovan, and the essentials of power from Richard Cedena. I read Bob McCarthy’s text on system optimization so many times that it completely fell apart. (My second copy is currently held together with packing tape.) It seemed as if the authors were speaking directly to me through their books.

Making The Most

Of course, this is only one side of the coin. Reading about how a GEQ works doesn’t help in deciding which filter to cut. Understanding the steps to make a basket hitch around a beam is not the same as fumbling with a shackle while balancing on that beam, 60 feet above the ground.

Books prepare us for practical experience but they don’t replace it. However, they’re still quite valuable. They can help us make the most of the practical experiences that follow, particularly in areas where “guess, test and revise” isn’t the healthiest approach, such as power distribution.

Books can also teach us why we do things the way we do, and they can give us the vocabulary necessary to discuss these ideas with others. But most of all – and now we get to my primary point – books are yardsticks, just like my closet doorframe.

One of the books I purchased dealt entirely with signal metering. It was a small, thin, non-threatening thing, and it burst my bubble. I found the book confusing, frustrating, impenetrable. I remember thinking, “Who could possibly want to read this?” as I put it back on the shelf.

Revisiting The Premise

The book was never at fault, of course. It was an advanced topic, and I simply lacked the prerequisite knowledge. Rather than recognize this for what it was, I blamed the book.

A couple of years later while rearranging my shelves, I came across it and flipped to a random page, realizing, “Hmm, this doesn’t look too bad.” I ended up reading it from cover to cover, grasping the discussion perfectly well.

In the intervening years, I’d deepened my understanding of the relevant topics to the point that I could understand what the author was saying. All the while, I had gone right on thinking that it was beyond me because I never checked.

The contents of the book hadn’t changed; the contents of my brain had. This change was so gradual, as with my height when growing up, that I either hadn’t noticed or taken time to reevaluate.

A friend once told me an Indian folk tail that makes the point better than I can. A trainer buys a baby elephant and chains her leg to a metal stake in the ground to keep her from wandering away. At first the elephant tugs at the stake but eventually learns that she’s not strong enough to pull it out of the ground, so she stops trying. Years go by without the elephant ever tugging at the chain.

Later, when the elephant is fully grown, a passerby stops to talk to the trainer. “You fool!” he says. “Your elephant will escape. Why, she can pull that stake right out of the ground!”

“Ah,” the trainer replies. “You know that, and I know that.” He then gestures to the elephant. “But she doesn’t.”

Putting It Into Practice

Another friend, this one a physicist, once bought me a book about the physics of musical instruments. The bits I can understand are fascinating, but much of it is too advanced for me, so mostly this book sits on the shelf.

But because I don’t want to end up like the elephant, once in a while I retrieve it and flip it open – to test the stake. If you’ve got your own archnemesis – a book, a skill, a fitness routine, whatever – that’s defeated you in the past, I encourage you to give it another shot. What you find may come as a pleasant surprise.