I recently penned a piece for a musician’s magazine entitled “Working with the Sound Engineer.” It coaches musicians about arriving at the gig with an open mind, a cooperative attitude, coming prepared with supporting documentation (input lists and stage plots), and being ready to work with the audio personnel so that the show will sound the best it can.

This piece presents the other side of the same coin, looking at things from the perspective of the audio engineer. If you’re new to the sound business, or if you’ve been doing large, well-organized tours with plenty of advance planning and suddenly find yourself at a modest one-off, than this should speak to you.

Suspicious Minds

Many bands that play weekend gigs in small clubs, and the occasional party or wedding, are not likely to have a good understanding of how to interface with the sound guy or gal who’s “out front.” More than a few are suspicious of this new character who has temporarily entered into their world. Not uncommonly there is a measure of hostility – perhaps incurred by recalling a bad past experience – and sometimes there is even a downright lack of civility.

But as long as we remember that we’re engaged in what is predominantly a “follow-on” trade; that is, being of service to those who are making the music, giving the speech, or otherwise entertaining the audience, we can usually deflect animosity and turn it into good will, merely by being communicative. Not always, but it’s always worth aspiring to.

The first moments when meeting the performer(s) will probably define how the rest of the gig will turn out. I suggest taking the initiative. Introduce yourself and make a few short comments about being glad that you’re working with him, her, or them, and clearly identify that your role is to help the show sound great and function smoothly.

You can say you’ll make them “loud and proud” (perhaps for a rock band) or “clear and distinct” for an orator or comedian – or whatever other encouraging words might apply to the specific situation. Conversely, it’s never a good idea to threaten inferior results if they behave badly, even though some occasionally will. It will only reflect badly on you.

Keep in mind that the performers might be a bit nervous, especially if they’re not used to working with an audio engineer. This could be an unusually large gig for them. Maybe it’s a multi-act lawn party or a small festival, and they have little understanding of how to navigate set changes with other acts. I’ve seen seasoned performers fall apart when their normal routine is altered or when they’re faced with sharing the same stage with another act that intimidates them.

In The Details

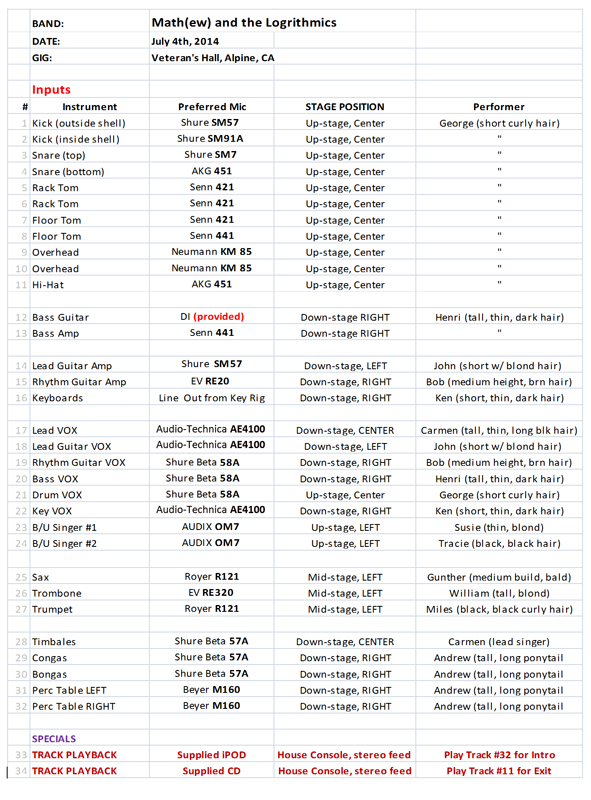

Being prepared is always a good thing. Start by having an input list “template” available, and ask that someone from the band fill it out, if possible. This is much more professional, as well as being a time saver, than writing on a blank sheet of paper. Figure 1 provides basic input list format.

If the act you’ve just greeted is not the first (or only) act, draw out a quick stage plot (Figure 2) so that you know what goes where, even if you won’t be situating the band gear yourself. After five hours in the sun, it’s really easy to forget who’s who, and what instrumentation each act will be using.

Discuss stage monitoring and miking so that you know what each member of the ensemble needs. I’ve been in situations where not a single person thought to tell me that side fills are critical because the lead singer moves all over the stage – until about one minute before show time.

The brief here is do not wait for an impending disaster. Have a checklist ready and work through it. Prompt the talent. Do they need side fills? Who needs a wireless? Do they need any additional mics other than those they’ve brought with them? Will there be any guest artists called up? And so on.

All too often a band member will tell you where to place his or her mic but completely fail to mention that it must be a certain type of wireless, headset, or other special requirement…or even where it’s supposed to be sourced from.

Further, bands will often call up a guest performer with no pre-warning and expect that somehow, some way, a guitar and vocal mic will magically appear.

Ground Rules

While remaining cool and collected, make it clear up-front that last-minute requests for stage monitors, extra mics, DIs, and other equipment cannot necessarily be accommodated.

Equipment requirements must be stated in advance. Someone in the band might suddenly remember that two more mics are needed, and the sax player’s wireless needs to be patched in just as the band is tuning up and getting ready to play. Head this off at the pass, Lone Ranger. Discuss such needs in advance.

In the heat of the moment, while preparing to perform, it’s the rare musician who is able to realize that you can’t pull rabbits out of a hat. Performers are focused on themselves, completely forgetting that the mics and DIs have to come from somewhere – and need to be connected by someone – who quite likely should be completing a line check rather than running around backstage locating more equipment.

This approach may not stop the talent from making unrealistic requests, but at least you’ll keep your own integrity intact by anticipating as many problems as you can at the outset. A good policy is to always have a couple/few extra mics on hand, located side-stage, cabled, tested, and ready to use. Ditto for stage monitors. Of course, on budget gigs, extra mics, extra stage monitors, and unused console inputs are not always available.

Steady & Focused

Make it (politely) clear that the PA system is not to be adjusted, re-positioned, re-aimed, or even touched except by yourself or one of your team. And by all means discourage that band member who decides to plug an “extra’ stage monitor into the paralleled output of a main bi-amped loudspeaker, causing its amplifier to shut down, resulting in only HF on one side of the stage.

Overall, learn to not take comments from performers too seriously, either before the show or after. A good deal of their perception of a good sounding gig is more about how they felt emotionally while performing, what the monitors sounded like, and how their friends and the audience reacted than it is about the quality of your services, the mix, or how the system sounded out front.

Finally, be humble but never humiliate yourself. Don’t be talked into doing something that won’t serve the common purpose. And even if something goes wrong, and at some point it will, stay as cheerful as possible so that everyone goes home having made the best of it.