There’s a reason musicians express so much fondness for stage techs. They’re often the only thing standing between an on-stage disaster and a smooth show.

I know this because I’ve also had the dubious pleasure of spending large chunks of time as a touring musician without a dedicated “helping hand” and teching my own gear. So when it comes to the whole “willing and eager” thing, at those times I only want to get through that run of shows without anything going off the rails.

Unfortunately on tour, something almost always breaks – usually more than one thing and usually right when you need it most. When you’re on your own, fixing it and sticking with the unwritten (and oft broken) rule that says “Never let the audience see you sweat” is challenging or nigh on impossible. Suffice to say I’ve spent a lot of time on stage fearing the worst but hoping for the best until a well-aimed beer can or Murphy and his cursed, all-pervading law strikes.

Knowing I could be without a tech – or working with someone I’ve just met that afternoon at sound check – I back up everything, from sounds to keyboards to things that can easily go missing; power supplies, adapters, and cabling. I label or color code everything so if my hands are full of keys, I can say, for example, “Swap out the MIDI cable with the red tape” or “Open up ‘E1’,” the case behind my amp and grab the backup sustain pedal, please.’

Granted, even when you think you’ve thought of everything, fate (no doubt giggling maliciously at your expense) may prove you wrong, leaving you hoping you’ll get through the set without further hiccups. Doing so requires having a “Plan B” whether you have a backline tech or not. Being able to implement that plan yourself (or have it implemented) without running around the stage like a crazy person requires practice – even if it’s just playing a game of “If ‘x’ happens, what will be the result?’ in your head, or preferably, with your tech.

The Most Important Thing

In my experience, ideal stage technicians share similar qualities in their approach, personality, and skill set. i.e., they’re multi-talented, pride themselves on accomplishing whatever is required quickly and competently, and are always willing to learn, adapt, and solve issues on the fly.

As importantly, in action on stage, they live by the quote of Karl Winkler that I concluded with in my last piece of this ilk: “The most important thing in the world is what is happening on stage right now.” Karl was talking about monitor engineers, but in my view, it’s just as crucial for backline techs, if not more so.

Case in point: In the late 90s with my band Moist, I toured with a brand-new AKAI S-5000 sampler rig and a “rock-godesque” multi-keyboard setup. It was pretty impressive for the time, had plenty of built-in redundancy, and was designed and overseen by a dedicated keyboard tech who’d spent an entire Montreal summer with me in a dark rehearsal space, programming on a platform that was far from bug-free.

2022).

This was also one of my earliest experiences with in-ear monitors, which helped allow said tech (who was far more reliable than my rig) to say, “Do not go to the samplers. They’re down.” That was to be expected. At the time, my three-tiered backup rig was far less likely to crash (or fail in any way) than the S-5000.

In fact, my multi-tiered synth/organ simulator/controller/MIDI switcher monster only crashed once, albeit far more spectacularly than the samplers ever did, falling on its back on a particularly bouncy stage in a way that you couldn’t possibly fail to notice.

But, initially, nobody did – myself included. At least until I reached over to nail a tasty “animal screaming in pain/exploding submarine sound” on the synth and my fingers met empty space. When I had a free hand, I waved and gesticulated. I looked around wildly, but because a larger-than-usual complement of fans suddenly decided to flash the band, no one came to my rescue until the next song.

The days of multiple backline techs and ridiculous 70s-style keyboard rigs are over for me. These days I tend to travel with one stage tech that does the entire gig alone or shares duties with someone local.

Generally speaking, that works out fine. I’m blessed to have worked with pros and enthusiastic, if less seasoned, newcomers. My rig is more compact and stable, and is configured to provide complete redundancy. Theoretically, if one device decides to not play nice, my show won’t grind to a halt (knock wood).

Still, any on-stage issues – mine or another musician’s – need addressing lickety-split, so depending on how much time I have with a new tech, I’ll either cover everything – setup/teardown, show prep/pre-show settings, troubleshooting – or as much as I can (which might amount to, “If I’m looking at you, I need you – double quick’).

That said, I’m fully aware that when there’s only one person to cover the entire stage (whether they know the gig and the gear inside out or they’re someone we just met at sound check), they might be dealing with multiple issues simultaneously – tuning a guitar, running messages to monitor world, troubleshooting something else entirely, etc. It takes a certain type of personality to cope with being tasked with what amounts to several jobs in one at the best of times.

Whether they’re a one-person, one-stop shop or part of a team, the ideal technician – in my opinion – is constantly watching, constantly striving to streamline every aspect of the job without sacrificing efficacy and doing so calmly. Not only during the show but before.

Case in point: We were roughly seven shows into a mid-90s theatre tour. Full crew – backline techs for everybody, multiple buses, a truck hauling production, dedicated TD and TM – all highly talented road warriors who were obviously filling time between far better gigs by touring with us.

And then there was Timmy. That wasn’t his name, but someone coined it, and it stuck. It’s changeover, 15 minutes from show time.

Me to keyboard tech extraordinaire: “Any idea where the spare keyboard is?’

Keyboard tech: “It should be right over there. That’s where I told Timmy to put it here when we loaded in. Timmy? Where’s the spare?’

Timmy: “It’s in the bus.”

Keyboard tech, sighing: “And where’s the bus?”

Timmy: “At the hotel.”

To Timmy’s credit, he vanished like smoke and quickly hauled his tail the two blocks to the hotel and back. And he didn’t make that same error again.

Personality Traits

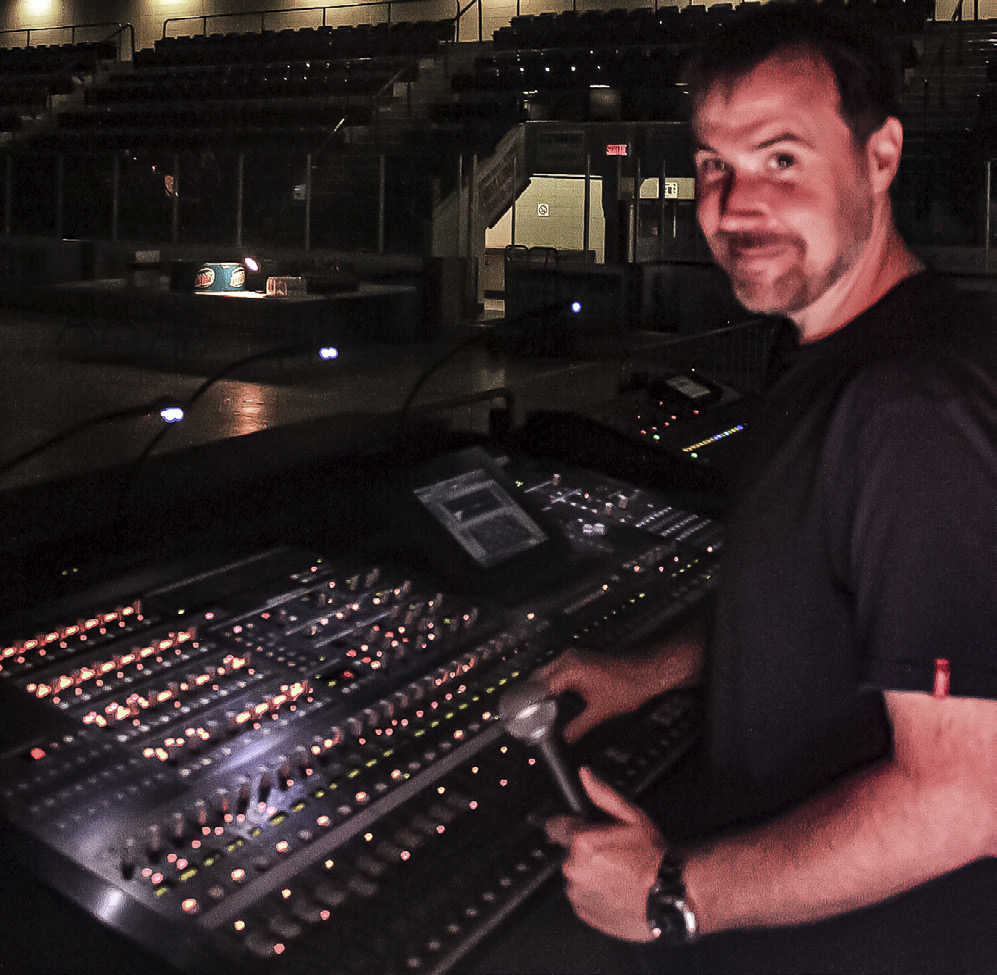

Given our increasingly lean tour team, my good friend and Moist’s long-suffering front of house engineer/tour manager Matt Lamarche also depends heavily on our tech and has some opinions about what kind of personality a tech should have.

They are as follows: One – “People who take the initiative, gain experience on their own but ask questions when unsure about something; problem-solving and troubleshooting are key.” Two – “People that aren’t alcoholics.” Three – “People who don’t spend their whole day on their phone.”

sounds of the night” in a small Northern Ontario arena.

There’s no wiggle room on Two or Three; however, we’re happy to work towards fully embracing rule One. So, if someone isn’t getting the workflow down quickly, we’ll start with gentle promptings. For example, Matt might say, “Hey, maybe you should go down and get the gear ready so we can get out of here.” In other words, trying to suggest what should happen next to help the person process the procedures.

Liberally applied, that prompting usually does the job, and nobody finds themselves the new owner of a Greyhound ticket from the middle of nowhere to wherever they call home.

Well before that, even if things don’t improve, Matt adds, “I’ll say, ‘Let’s go have a beer.’ Then the father in me comes out. I’ll tell them a few stories of how it was when I was learning. So, when you have someone with experience who’s trying to share it with you – clue into that, ask questions if you’re unsure, or observe more and pay more attention. Then I’ll give them another chance or two.”

And if that doesn’t work? “Maybe they’re not cut out for the gig.”

Given that working as a stage tech or a member of local crew is the kind of job someone looking to get into the touring business starts with, I also have some advice, first, for musicians. If you’ve toured with a backline tech for a while, it may seem like they can almost read your mind. They can’t. They’re just good at their job. Anyone who hasn’t worked with you needs your help as much as you need theirs, so give them information – preferably a comprehensive rundown of your needs, setup, and how to troubleshoot it, and provide that ahead of time, in writing.

I offer this advice to anyone new to a job as a tech:

One – Measure twice, cut once. (Anyone, in any role, on any tour/gig, large or small, will see how that applies to a live setting).

Two – If you have a question, ask it (repeatedly if necessary). I’m happy to answer the why, how, and when of workflow/troubleshooting or anything at all.

I will even answer multiple times because, A) I know there’s a lot to deal with from shows where our crew consists of one person doing FOH/tour management, or (as previously mentioned) I’m my own technician, B) I want everything to go smoother than when that’s the case, and C) I get the sense you’re trying to find a better, quicker, or more reliable way of doing things than I could and that you can tell the difference between something that’s going to be an unwelcome or welcome surprise for me when I hit the stage.

Case in point: One particularly excellent and deeply experienced tech I had the luxury of doing a run of shows with happened to be looking over my shoulder during sound check and realized a small, road-weary synth’s various dials were altering my crushing lead sound without my touching them. My solution

was toggling back and forth between patches to reset. Not ideal.

His was wedging double AA batteries between the dials so they could still be manipulated but wouldn’t move otherwise. A temporary fix, sure, but it got us through the next few gigs.

Needed Or Not?

Granted, not everyone is that motivated. Sometimes a lesson in responsibility is required. For example, an extensive cross-Canada tour had us hitting a mix of excellent as well as somewhat dodgy venues.

Luckily, we had a full crew – LD, ME, FOH, and two stage technicians, including one relatively new person. There’d been a couple of issues with him, notably a tendency to be late waking up for load-in. Naturally, we expected that after our tour manager brought that up, the problem would be resolved. One day, however, after he’d had a few more than one too many drinks the night before, the TM decided a more pointed lesson in punctuality was in order.

Figuring our man would sleep most of the day if no one bothered him, we didn’t bother him. We made every effort to ensure he got his “beauty rest.” Consequently, he slept through load-in, set up, and sound check. But, as it turned out, he never appeared to need that much rest again after that. Shame does wonders for one’s motivation.

“Hopefully, that was a long-lasting lesson,” Matt says. “That he realized you’re responsible for yourself. You make sure you show up on time, ready to do the gig, and if you’re not there to do it, somebody else is, and it’s like, are you needed or not?”

To reference a different type of crew, if you’re new, figuratively, you’re wearing a red shirt – and we all know what happens to those folks when they beam down into something they’re unprepared for. (For the uninitiated, this is a reference to the original Star Trek TV series.)

Incidentally, if you are, in actuality, wearing a red shirt, or a white shirt, or loud pants, or anything that isn’t some shade of “hard to see even when the lights are up,” the likelihood of something unpleasant happening is amplified – at the very least, a dressing down from someone who, wisely, is wearing a black shirt.

That may not seem important if you’re working for a band that’s just starting out, one that, let’s say, occasionally supports better-known bands at a local venue or is a perennial second or third on the local bake sale/music festival in your town. The act you’re working with may not care, but if you dress and move like a ninja (and, like any ninja worth their salt, make sure you’ve got all the tools for the job close at hand), if you look like you really want the gig, chances are the bands farther up the bill, and their crew, will take note. It might lead to more gigs – or it might not, but at the least (even if everyone else working the show thinks the band you’re working with is a hot mess) they’ll appreciate your work and remember it should you come looking for a job down the line.

If, however, as Matt puts it, “You’re standing there with a beer in your hand talking to the opening band’s girlfriends and the local crew is on stage taking your stuff apart, it’s like, seriously? What the… ?”

Bluntly, you’re probably getting in the way if you’re not part of the solution – a lesson I learned working on a local crew well before ascending to the lower rungs of the middle of the Canadian music industry ladder.

Case in point: It’s the mid-80s, and a reasonably well-known UK-based band is loading full production into a smallish, highly reflective, and still icy arena at the university I’m attending, and at a time of day that I know now means they’re running very late.

My only job description was to “Move stuff quickly when you’re told to.” So, I walked onto the truck to grab my first piece of gear, utterly alone. The band’s stage manager – very British, very imposing, very aggravated given the time of day, pauses, clearly waiting for someone to join me and help.

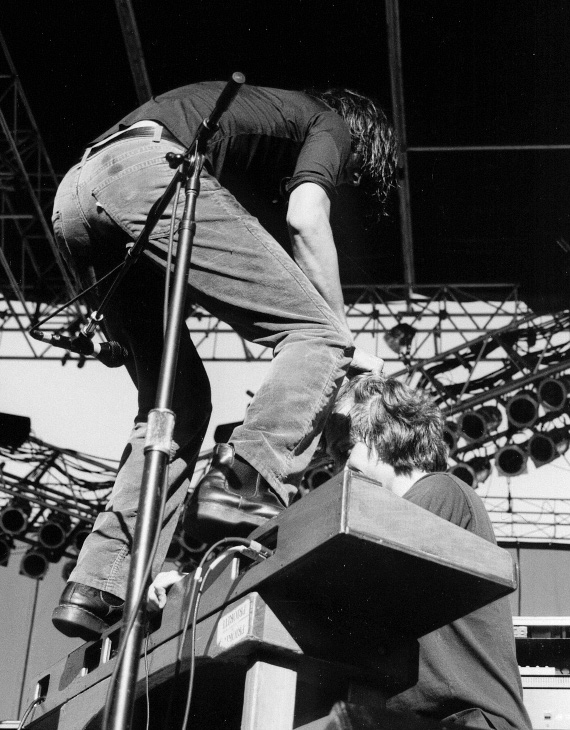

from the author: “I should add that David’s habit of doing this

almost got him tossed out of a gig once – he was on top of

Mark at a university show in 1993 – a security guard working

the pit turned around, saw David on Mark, grabbed Dave and

said, ‘that’s it, you’re out of here, buddy’ – our drummer got up,

punched the security guard, and the whole guitar rig fell over in

the melee. Big fun.”

But, at my insistence, he tipped a large loudspeaker cabinet my way – a cabinet I promptly dropped. He was not pleased and expressed that displeasure in a very imposing and aggravated manner, using a few phrases I didn’t quite catch but which I took to mean, “If you can’t handle it, get out of the way.”

Defiantly, I lugged that first cabinet out of the truck all by my lonesome but made sure when I went back for another, I did so in the company of someone who would partner up with me to catch and carry anything that he tossed my way. Rightly or wrongly, if you don’t learn from your mistakes, you may be remembered, but not fondly, and for all the wrong reasons.

Showing Potential

As previously noted, I’ve had the opportunity to work with some real pros – people who were clearly slumming it on our tours, but who sucked up knowledge like sponges and spread that knowledge freely, even when it contradicted what a band member thought – firmly, but compellingly. Folks who not only busted their tails off stage but filled in on acoustic guitar for a few songs, who, even in the face of outright hostility from a poorly planned festival’s organizers, made it work and still came up smiling, and who, in one case and even when the samplers went down (and I was freaking out because one of my keyboards was literally on fire), was eminently patient with me and made me feel like everything was going to be OK.

I love those people. But I’m increasingly fond of working with those who aren’t as seasoned – i.e., folks with potential, eager to learn, and excited to do so. One in particular is someone who’s been out both pre- and post-pandemic with us, sometimes as the only consistent crew member gig-to-gig in some of the most punishing travel circumstances I’ve experienced: our manager’s son and a musician in his own right who we’ve nicknamed “Bullet.”

As an example, we were a couple of shows into his first run with us. It was a club date at Toronto’s Horseshoe Tavern, added in for the sheer fun of it the night after a larger show at another local venue. And mid-song, my keyboard stand started collapsing.

Bullet (already moving to avert disaster): “We’ve got another stand.”

Me: “Great, just keep holding this one up until we get through this tune.”

Bullet (now in front of me, crouched down and manhandling the rig to keep it in place even as I’m still pounding on it like it’s my sworn enemy): “Roger that.”

That was pre-pandemic and I’m pleased to say he was back again for summer 2022 – including two shows where he was the only tech working in the stage/sound/light department that we didn’t meet day of show. As I said, he’d worked with us before as part of a larger and relatively consistent crew. This

past summer, however, on several gigs, well, he was all there was; there weren’t no more.

Because he spent some time with us in rehearsals before each run, he was ahead of the game and knew (because I told him and then told him again): “Don’t stack our gear in the position it’s going to inhabit on stage during the show when we load in. You’ll have to move it again to set it up. Better yet, don’t move anything yourself. Just get on stage, tell the loaders to bring you the gear in the order it’s packed, and ask them to put it where you know it goes.”

Bullet: “Roger that.”

On both runs, we covered and re-iterated the basics: this is how everything works, this is what to do if it doesn’t, this is what you need to keep an eye on (always), this is what you’re going to need to do in situation x, y, or z. This is where and when everything goes on stage, in the pack, or (in the case of my 3U MainStage rig, “the brain”) into my waiting hands post-show.

Were there hiccups? Yes. Does he still have a lot to learn? Of course. But he’s willing to. It takes time to develop the ability to manage local/house crew and work quickly and precisely while putting out any fires that crop up quickly. And, frankly, it’s satisfying watching someone learn, especially someone who, as a musician, can take that experience into their gig.

In fact, watching our manager’s son interact with a seasoned tech working with one of the other bands we were playing with, seeing the care and consideration the experienced person was willing to lavish on our hulking greenhorn reminded me of the times other musicians and crew members have taken me aside and offered advice, corrected my errors or suggested a better way of asking for something when I’m speaking musician – i.e., “I don’t know, it just sounds crispy and purple.”

And maybe that’s the most integral quality all the very best technicians I’ve worked with possess: the desire and capacity to be part of the solution whenever they’re needed and whatever the situation is – even if, strictly speaking, it’s not their problem.