One day in the mid-1990s, when I was managing a large sound company, one of the account managers came to me and told me he was demoing “The Refrigerators” on our soundstage for a club client later that day. He said, “You built the crossovers for them, right?” I said I had, and he asked me to go back and have a listen to them before his clients got there, just to make sure they were doing what they ought to be doing. I said I would.

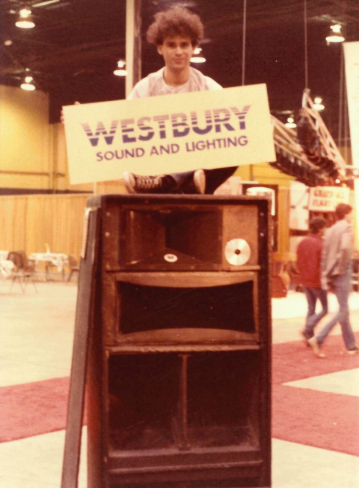

The Refrigerators were a set of four cabinets, our first attempt at a four-way, full range, all-in-one PA box that we’d built in 1983. They were built around an Electro-Voice Sentry-IV bass cabinet, our proprietary LM-90 low-mid device, a JBL 2380 bi-radial horn with a 2445 driver, and a Yamaha tweeter. The cabinet incorporated the Sentry-IV bass cabinet, but was roughly twice as deep to accommodate the depth of the mid device. This allowed us to enlarge the mouth area of the bass horn by about 100 percent.

These cabinets soon acquired their nickname because they were about the size and shape of a large fridge, and about as awkward to move around. They never were a huge success. I’d done an arena tour with them as mains in 1984, with not-great results, and after that they were relegated to occasional use as side fill monitors on large stages.

The Refrigerators were soon superseded by our second attempt at this type of loudspeaker, which used the same mid and HF devices but with a new, front-loaded 18-inch bass element. That cabinet was, in turn, replaced with a two-box system consisting of a twin 18-inch sub cabinet and the three HF components in their own enclosure, after we’d determined that the single 18-inch driver just couldn’t keep up with the mid and HF devices on a 1:1 basis. This loudspeaker was quite successful. If you worked at The Phoenix Concert Theatre in Toronto between 1992 and (approximately) 2006, you mixed on that PA.

A Startling Discovery

Somewhere along the line, The Refrigerators had given up their LM-90 mid devices to be re-used in the new system, and those had been replaced with a pair of direct radiating HH-1200E 12-inch drivers mounted on an inverted “V” shaped baffle (so they faced each other at about a 45-degree angle). I’d never heard this arrangement because it had been done in the intervening years between when I had left the company at the end of ’84 and returned in October of ’91.

I walked back to the soundstage, put a CD on and had a listen. My first reaction was something like “Huh…” as it didn’t sound like anything I was expecting it to sound like, and it didn’t sound that good either. I suspected that this was due to the new low-mid arrangement, but I popped the lids on the two crossovers just to see if they were as I remembered them. Everything looked ship-shape in the crossovers, which were state-of-the-art when I’d assembled them in 1983. I knew from the component choices we had made at the time that aging was very unlikely to affect the sound, even some 10 years later.

So, having ruled out the crossovers, I had another focused listen. After a while, it dawned on me… the sound just wasn’t coming out of all of the ranges at the same time! This is really the first time I can recall ever being consciously aware of that phenomenon.

The question then was, what, if anything, could I do about this? I knew that the answer would involve delaying some of the outputs, but I wasn’t sure how I was going to go about that. At the time, digital crossovers were just coming on the scene. We owned a couple of Yamaha D2040 four-way digital crossovers, but I hadn’t really had a chance to learn them, and they were already assigned to our main PA systems and built into drive racks.

Rejecting those, I moved on to the only other box that might work, a pair of Yamaha D1030s. These could be either a 1 x 3 delay with EQ on each of the three delay outputs, or a 1 x 3 crossover with delay but no EQ on each output. There just wasn’t enough processing power under the hood to do both. Now, this box (which was also sold as the DDL3 at some point) was a functional, do-the-job-but-nothing-more kind of unit. I’ve never heard anyone rave about the “sound” of the box, and I doubt there’s anyone working today who is nostalgic for using one.

Another issue was that when I got into the crossover menu, I soon found that the range of frequencies that were available weren’t quite right for the cabinet. Nonetheless, I decided that for experimentation purposes, they were close enough and proceeded to enter those. One thing that I neglected to mention earlier is that the “Fridges” were now a three-way cabinet, as the Yamaha tweeters had long since either died or been scavenged for some other project.

I quickly entered the closest crossover parameters that I could and then turned my attention to setting the delay times. This was years before Rational Acoustics Smaart existed, and smartphones (and their related audio apps) were barely even in the realm of science fiction, which made measuring the delay a challenge. At the time, we owned a DRA Laboratories MLSSA acoustical measurement system, but I hadn’t used it for a while and didn’t have the time to get back up to speed on it.

A Matter Of Precision

So, here’s a thing: We all know that 1 foot is approximately 1 millisecond (ms), but I maintain, and I always have, that approximations are not good enough when setting delay times in sound systems, especially at the individual component level. The drivers are not approximately “x” distance from each other, they are exactly “x” distance apart, and are not going to move in relation to each other.

What to do? Easy! I went into the Utilities menu on the D1030 and switched the “Units” from “milliseconds” to “feet and inches.” Why? A foot may be approximately 1 ms – but it is exactly one foot.

(Sidebar: The speed of sound, at sea level, at “x” temperature and humidity, yada yada… is actually 1.1 feet per ms (1100 FPS/1000 = 1.1), which means that if you’re using the old “1 foot = 1 millisecond” mantra as a rule of thumb, you’re building a 10 percent error into all of your guestimates. So if, for example, you have a set of delay loudspeakers that are 40 feet out from the mains, the actual time to those loudspeakers is 36 ms, not 40 ms – and 4 ms is a big error in timing and tuning. While I don’t make my living as a system engineer, it’s been my experience that when timing and tuning systems, the more accurate the delay settings, the more seamless and transparent the sound field between all of the sound sources will be.)

Then, because I knew how the cabinets were constructed, and the length of the paths the sound took (a long, tortured one in the Sentry-IV sub), I measured them with a tape measure and entered the results in the crossover.

I was gobsmacked by the results. Floored. Astounded. The Fridges sounded so much better that I could hardly believe it. Even with the not-quite-right crossover points, and as-good-as-they-could-make-it-at the-time late 1980s digital audio versus state-of-the-art early 80s analog sound and exactly the right crossover points, the difference was dramatic. I was especially surprised by how far up into the low-mid frequencies that timing error between the sub and the mids had been audible – easily up to 500 to 600 Hz, with a crossover point at 250 Hz.

That really was an eye-opening moment, particularly when I thought back on my early years in the business and how much time we had spent (or wasted) flipping phase (polarity) switches on crossovers trying to figure out if it sounded better in – or out – but in reality what we were doing was making slight timing adjustments when what we really needed was a bigger, more accurate one.

Did the loudspeakers sell? I don’t remember, but I don’t think so.

Repeating The Exercise

A few years later, when cell phones had become a thing, I received a call from the same account manager while I was on my way in to work one morning. The crossover had died at a club installation, and they had a big show that night. What should he do?

I told him to grab a pair of D1030s and meet me at the club, which was conveniently located on my way to the shop. This club, The Opera House on Queen St. East, had another of our proprietary PA systems in it… the follow-on system to the one at the Phoenix. This system consisted of a three-way trapezoidal box with a front-loaded 18-inch for the bass, an 8-inch JBL mid on a unique fiberglass waveguide developed and molded in house, and a JBL 2370 bi-radial horn with a 2425 driver on it. There were a few innovations with this box, but the big one was that the 18-inch had the full interior volume of the cabinet to work with as opposed to the separate (and smaller) LF enclosure on our second four-way design attempt. This was accomplished by sealing up the back of the mid driver in a fiberglass “dog dish” so the LF didn’t modulate the mid cone.

When I arrived at the club, I repeated the exercise of using a tape measure to set the delay times (again I was very familiar with the component placement in these boxes because I was involved with their development), played my trusty Ben Harper “Welcome to the Cruel World” CD for a few tracks to observe the results, and then continued on to the shop.

Popular rock singer Liz Phair played there that night, and I was told her crew was very happy with the PA. That rig was in the Opera House from roughly 1994 to 2004 when it was replaced by an Adamson Y10 system, so if you played there in that 10-year period, you were on another system designed and engineered in Toronto by the company I’d worked for.

Some months later, the account manager called me again to tell me that he’d finally received his replacement crossovers for the club, a pair of Dynacord DX34 or DX38 processors (I can’t recall which…), and was I available to come in and program them? Well, I wasn’t available… I forget why, I may have even left the company by then, but in any case, I told him, “Look, for every parameter in the D1030, there’s going to be an equivalent one in the DX3x, so just set those the same. There’s going to be additional parameters in the new units, but just leave them at their defaults, or not engaged, and you should be able to get sound to come out.”

This he did, and it worked. In fact, it worked so well, that when, a few weeks later, he had our head system tech come down with the MLSSA system to set it up “for real,” the system engineer took a few measurements and said, “What am I doing here?” There was nothing that needed to be changed.