Learning & Growing

The way I approach tuning a system grew out of these experiments. As I progressed to larger rooms with better acoustics, I discovered that feedback was less of an issue and that less EQ was required to achieve the levels I required, especially if the PA was separate from the stage area itself. I soon realized that every room is different, and as a result, I should never try to apply a one-size-fits-all solution.

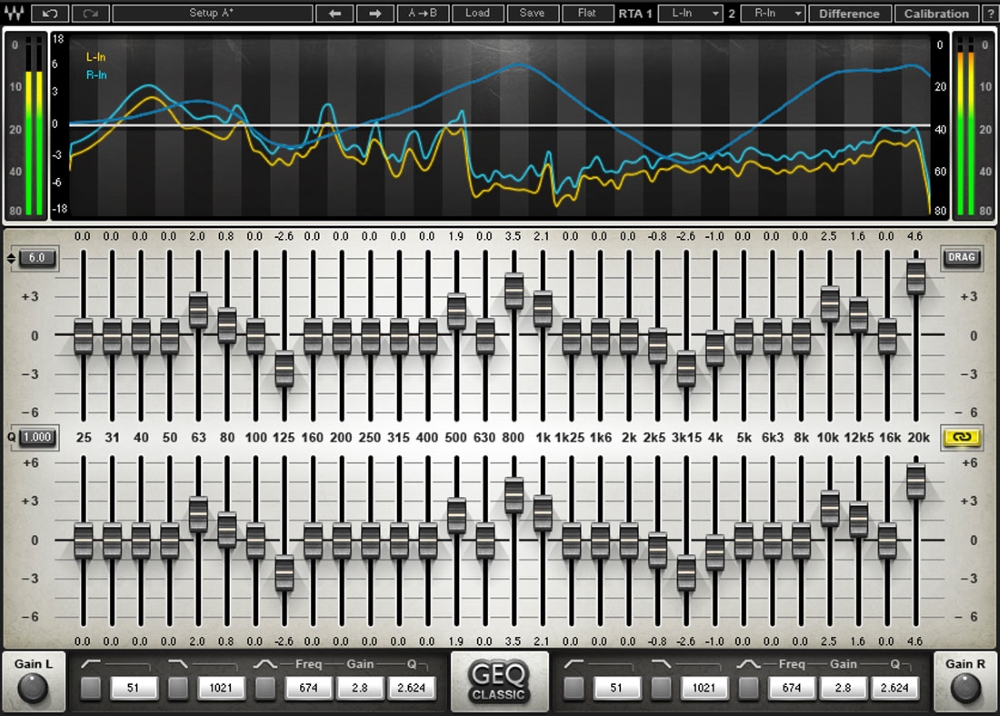

My approach evolved to more of a sliding scale where at one end I just ring out the system to get maximum gain before feedback, and at the other end, I’m just subtly sculpting the EQ.

Typically, smaller rooms with less-than-ideal acoustics are at the ringing out end of the scale while larger rooms with professionally configured systems are at the other end. However, the relationship is by no means linear so each room should be approached differently.

As noted, the fixed frequency nature of graphic EQs can be quite annoying, but nowadays most digital desks also offer the additional option of parametric EQs on the outputs. As a result, I’ve modified my ringing-out technique to take advantage of this, using parametric EQ with a narrow Q (lower resonance) to address the first three or four frequencies before moving on to the graphic EQ.

One of the most common methods for tuning a system is to play familiar music and listen to how it sounds; this can quickly provide a good idea of how the system performs in the space.

Over the years I’ve built up a series of sound check compilations for this purpose. When I’m working with a specific band I always try to listen to music in a similar genre but I also have certain “go to” tunes which are used to gauge specific characteristics of the system.

For example, a key aspect of line arrays is how the main hangs interact with the subwoofers, so I’m always keen to listen to the bottom end and make sure it’s in context with the rest of the frequency spectrum. As a result I use music with a pronounced bottom end for this purpose. The next thing I listen for is clarity in the mid range, this being the busiest area of the spectrum for most styles of music as well as the area where the room acoustics can do the most damage.

The Whole Picture

But listening to music over a system doesn’t always tell the whole picture. Once I was doing a gig in an underground venue located beneath a shallow pond. It was a long, narrow room with a stage at one end and a ceiling made of glass, which let in light through a few inches of water to create a pleasing underwater effect.

As usual I cranked up the PA and started listening to my sound check tunes, tweaking the EQ until I was happy with the sound. However when I started line checking the drum kit, there was a cacophonous racket and I soon realized that the glass ceiling was causing some unpleasant reflections of direct sound from the stage that listening to the PA had not prepared me for.

This illustrates the fact that listening to music over a system doesn’t always tell us everything about how the room will sound when a band is in full flow. Not only do we have ambient sound coming from the stage, which will be a bigger issue in smaller rooms, but we also have stage monitors to deal with, and of course, no audience yet. Therefore any tweaking done prior to the show itself can only ever be a rough guide.

Over the years I’ve studied how different engineers approach toning. Some use software, some use music, some use a mic at FOH, most use their ears, but few do it the same way. One thing that surprised me is the fact that rarely is the graphic EQ left flat. You’d think that in this modern age of high-quality gear and computer modeling that the vast majority of systems would sound pretty good out of the box (as long as the room isn’t too challenging), yet engineers still insist on wielding their graphic EQs.

I’ve often felt there’s a territorial aspect to this ¬– house engineers may be top dog in the venue but they have to hand their PA over to whoever turns up with the band, regardless of that person’s level of expertise or experience. Meanwhile, visiting engineers are keen to establish their dominance by stamping their authority on the system via the application of their own unique EQ.

Recently I was on a joint headline tour where both acts had equal billing but took turns playing last each night. It afforded me the opportunity to directly compare how the other engineer EQ’d the same system on a daily basis, and the results were quite illuminating. Not once over the month of the tour did we apply EQ in the same way; often we used quite different settings, yet we both consistently produced quality mixes night after night.

In other words it doesn’t really matter what methods are used to get there as long as we end up with a great-sounding mix and a pleasing listening experience for the audience, because that’s really what we’re all striving for.