In live sound we often talk about “tuning the room,” but what does this actually mean?

Different engineers approach it in different ways with differing results, and there doesn’t appear to be a consensus on the best method or indeed what the desired result should be.

So let’s explore the world of tuning and see if we can gain any insights into this nebulous activity.

What we’re invariably doing is applying equalization (EQ) to the outputs of the audio system to achieve the desired sonic performance, but no amount of EQ is going to change the nature of the room itself, so to call it “room tuning” is somewhat misleading. What we’re actually doing is tuning the frequency response of the system to better work within the context of the room acoustics.

This is not to say that it’s not possible to actually tune the room itself. It’s perfectly possible to alter the composition and configuration of the reflective surfaces as well as deploying resonators or damping the acoustics with baffles or heavy drapes to achieve the desired result.

However, this kind of treatment is usually applied when the room is designed, built, or converted from a previous use.

In my experience, very few venues were actually designed and built with live amplified music in mind. Many have been converted from different uses or are maintained as multi-purpose spaces for events with quite different acoustical demands.

For instance, a lot of venues are converted from (or still used as) theatres, which are spaces designed to acoustically amplify whatever is occurring on the stage area and transmit it to the back of the hall or up to the balconies. But this kind of acoustic amplification isn’t always helpful when you place a loud rock band and a powerful PA system on the stage. It’s just one of the issues we have to take into account when tuning the system.

Making Distinctions

When a system is permanently installed in a venue, it’s usually tuned by a system tech or house engineer, and when it’s set up temporarily for an event or artist, it’s usually tuned by the individual mix engineer. The approaches to the two are slightly different, so to draw a subtle distinction between them, I like to call the former tuning the system and the latter toning the system.

Tuning can involve setting up the crossover frequencies, configuring individual loudspeakers, and ensuring the whole system works together in the space. Generally speaking the aim is to attain as flat of a frequency response across as much of the space as possible to ensure the system can cope with the demands of a wide range of live presentations.

Once everything is set up, the system tech or house engineer will hand things over to the mix engineer. This can create an interesting dynamic at front of house because it’s quite common for mix engineers to be less knowledgeable about the system and venue acoustics than onsite tech/engineers and yet the mix engineers are usually cast in a superior role.

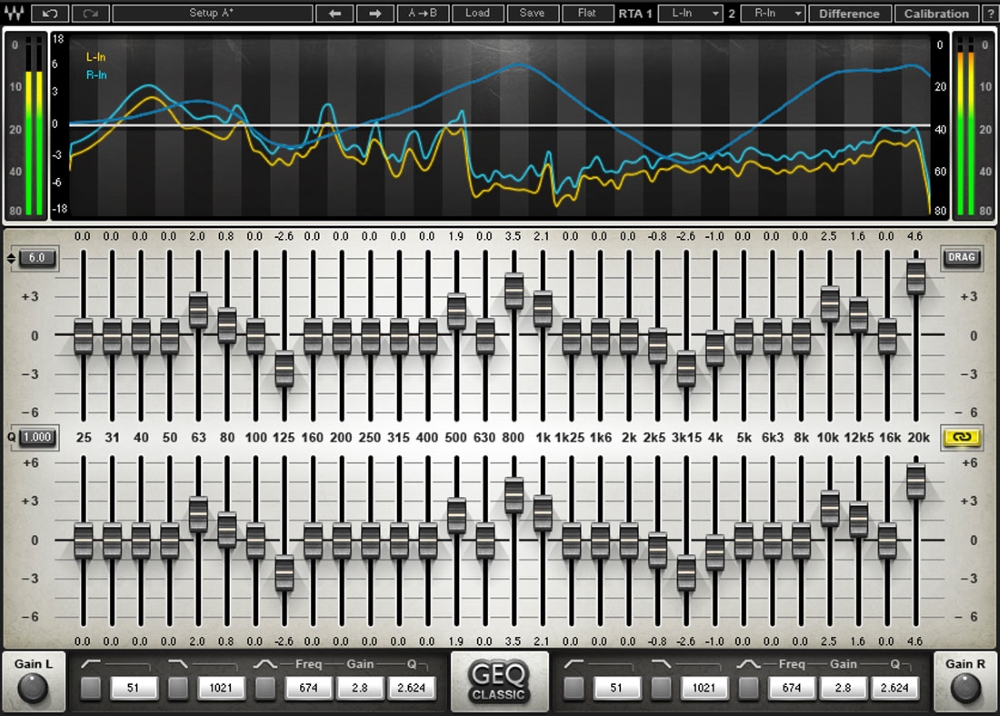

Traditionally, the tool for tuning has been the graphic equalizer. Graphic EQs have long been favored on outputs because they provide quick and easy access to 31 filters at set frequencies.

As the name suggests, graphic EQs also provide rather handy visual feedback on exactly what’s being applied across the spectrum. It can be very handy in making sure we’re not over doing it. The only issue is that the filters are all at fixed frequencies – anyone who’s needed to cut a little 9 kHz knows how annoying this can be.

When I first started in live sound, I worked at a small venue where I was typically both the house and mix engineer for the entire night (which would often involve mixing three to five acts). Being completely self taught, I had no idea what to do with the graphic EQs so I just ignored them.

After the first few gigs I was immensely frustrated at the amount of feedback generated by my attempts to get the vocals on top of the mix. So I tried to convince the guitarists to turn down their amps, but they’d complain about how loud the drums were and add that they needed to hear themselves, and thus would generally refuse to turn down. I knew that somehow, I needed to come up with a way of getting more gain from vocal mics so I went into work early and experimented.

What I discovered was that if I set up a mic in the middle of the stage and kept turning it up, feedback would begin. No surprise there.

However, I also noticed that it fed back at the same frequency every time, so I went to the graphic EQ and started pulling down the little faders until the feedback went away. I found that if I kept doing this for the next few frequencies I could significantly increase the level of the mic and minimize the feedback howls. I was quite pleased with this discovery – little did I know that engineers had been employing the “feedback method” to ring out PA systems and monitors for years.