The majority of electric guitar players will tell you that they much prefer the sound of “hardwired” guitars versus going wireless. When you “radio” a signal, there’s not only a sense of disconnect, but the tone never seems quite right.

I noticed this years ago when testing a guitar splitter. One of our engineers sent me a prototype, and after a few minutes of testing, I called him up and said that it worked well but was not quite right. He said, “What do you mean? It is class-A, 100 percent discrete, and has Jensen transformers. It’s perfect!” I replied that while it might be technically perfect, there was still something wrong.

Eventually, we figured out that it had to do with how the pickup was loaded, as well as how tube amps differ from solid state inputs. (This problem is not only common with wireless systems but all types of guitar signal buffers.)

Applying The Load

To solve the problem, we added a control that would enable the guitar tech to adjust the load so that the guitar would sound right. For this to work, the load needs to be applied directly onto the pickup. In other words, if you connect the guitar to a buffer and then try to adjust the load, it will not work. This also means that it has no effect on active pickups.

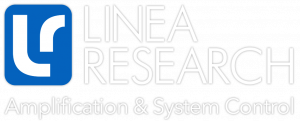

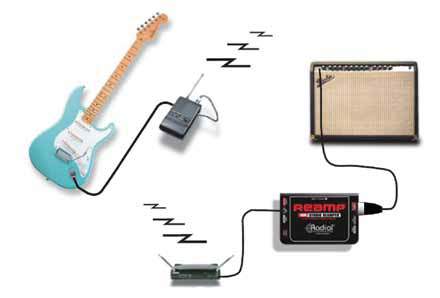

When using a wireless system, the guitar is connected directly to the wireless transmitter, which then buffers the signal and sends it to the receiver.Then, that output is either routed to the guitar amp, or a fridge full of pedals, or to the front of the stage so that it can go to the pedalboard and then back to the amp (Figure 1).

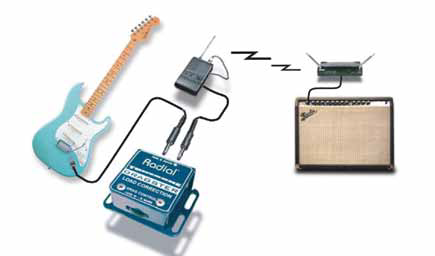

Because the wireless system is a buffer, the load must be placed in between the guitar output and the transmitter. Radial Engineering makes a device to do this called the Dragster. It’s designed to be attached to the guitar strap and then simply wired in series (Figure 2).

Even though this approach works very well, the last thing a guitarist wants is another widget on his strap. A number of artists have also been implementing an old recording trick known as Reamping on the live stage.

When doing this in the studio, you basically take a dry track from the recording system, send it out line level to a Reamp device (“Reamper”), which then convert the balanced signal to an unbalanced one that is better suited for a guitar amp. This enables the studio engineer to capture the performance and worry about getting the “ultimate” guitar tone later.

It works much the same for live. You take the output from the wireless receiver and send it through the Reamper to get the same effect (Figure 3). By converting the signal, the wireless system sounds smoother and more natural. And when artists are happy, they perform better.

In The Field

A few years back, mix engineer Brad Baisley talked to me about his work with Reamping and related facets for noted country artist Clint Black, and he provided me with this overview:

“I started formulating my approach after a show where Clint expressed concern that his guitar tone was dull. The guitar tech, Kenny Barnwell, and I were also tired of battling noise emanating from the wiring to and from the pedal board. I knew that the 100 feet (each way) run of 1/4-inch cable was primarily to blame for both problems – not the modern RF equipment he was using.

“We added a Radial Headbone amplifier switching device that allows two different guitar amp heads to be used with a single speaker cabinet, and then also decided to try a Radial ProRMP Reamp box as well as an SGI interface to boost the signal. We were immediately happy with the result, both in terms of sonic quality and noise level. Clint noted that his guitar sounds much more natural, with smoother, more extended highs and fuller low end.

“Another bonus is these devices have XLR interconnects. If the 100-foot cable loom we built is ever too short, I can dig into our audio spares and help the techs extend the wiring with no loss. And, locking XLR connectors add a considerable amount of security.

“The output on the Shure UR4D wireless receiver we use is 200 ohms, while pedals and amps are designed to see much higher impedance. The level of the output is also far higher than that of a guitar. This leaves you having to turn down the output on the receiver compromising on gain structure and signal-to-noise ratio. The Reamp solves this elegantly.

“We also often find that some local PA providers run cross-stage feeder on the downstage lip of the stage, so running long lengths of 1/4-inch cable parallel to it is just asking for noise issues. But with an all-balanced signal flow, that is now barely a concern.

“When setting up Reamping, first we make sure the levels on the wireless receiver are correct. The UR4D has a digitally controlled level trim (we have it set it at unity), and a Mic or Line level switch on the back for the XLR output (we set it to Line to send as hot of a a signal possible to the Reamp box). The companion UR1 beltpack transmitter has coarse and fine gain controls, and we also set these both at unity.

“With the pedalboard connected to the amp through the SGI, we then plug directly into the pedalboard input using a short 1/4-inch cable. We do a sound check of the guitar, using our ears (and maybe an SPL meter or VU meter on the console), evaluating the loudness of the guitar.

“After that, we plug the guitar into the wireless beltpack, and connect the pedalboard to the wireless receiver through the Reamp. The level on the Reamp is turned way down, and we slowly bring it up until it matches the level noted earlier.

“It’s a good idea to A-B back and forth several times to further dial in the level on the Reamp box. It puts us into a unity gain situation where the wireless (and cabling from it) will have the least effect on the guitar tone. We also have a Radial BigShot ABY bypass switcher on the pedalboard with a 1/4-inch plugged in and hidden under the pedalboard for a backup in case there are any issues with the wireless. It’s easily accessible and can instantly be activated using the switch.

“I’ve recently transitioned to a position doing monitors for Blake Shelton. We’re embarking on an eight-truck, full-production tour in 2012. During a recent production rehearsal, Blake’s tech and I revamped the instrument wireless setup, moving all of the Sennheiser inbound RF into racks and networking it for easy coordination.

“In order to move the amplifiers off the deck for a clean look, we implemented four sets of Radial SGI and ProRMP (as described above) for acoustic guitar, electric guitars, and bass. So far, so good!”