With the advent of digital consoles, the monitor engineer’s ability to reset the entire desk with the push of a button is a powerful tool.

However, there are many situations where the console must be adjusted from scratch or “zero initial data,” whether it’s a festival, support act or a one-off. Doing a little homework in advance can save valuable time.

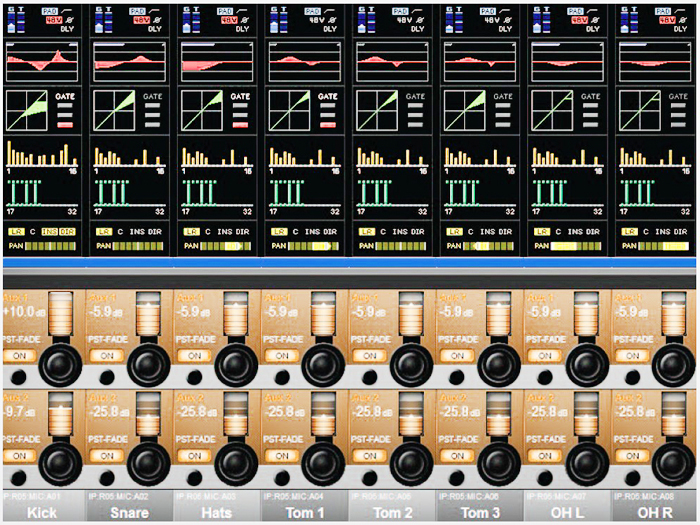

Look at everything that must be taken care of on the console before the band is on stage: inputs and outputs named and patched, gain, high-pass filters and phantom power set, effects named, tweaked and patched, GEQs patched, matrix named and patched, user-defined or macro keys programmed, monitor cue on master fader, then store all of that as a starting scene.

By studying the artist’s input list and plot, and making some educated guesses (given the band’s musical genre), you can set up the inputs. If active instruments – like keyboards and guitars with on-board electronics – are plugged into passive DIs, while active DIs are used to amplify passive instruments that need gain, channel gain settings will be more predictable. Likewise check the pads on DIs (and condenser microphones) before they go on stage.

If there’s a place at the end of the input list, or even somewhere in the middle, it never hurts to add one or two “oh by the way” (OBTW) channels into the console file, as invariably there’s something not accounted for in the band’s paperwork that’s been added along the way. If the piece of paper taped to the splitter and the file in the console don’t match, it’s tempting to fix it with a “soft patch” but I recommend “one-to-one.”

Meaningful Labels

Channel EQ can be quickly set with good starting positions for how you like to work using the console’s EQ library, which is a place to store EQ presets. Knowing the EQ filters that are the usual starting point for standard mics and typical applications, you can save the presets with meaningful names.

For example, you may cut some low mids and add some 1 kHz “click” on the kick drum using a (Shure) Beta 52, so by making a “Kick-B52” EQ preset, you can set that channel by just calling the preset to your selected channel with a touch of the screen or a click of the mouse. This is quicker than tweaking gain, frequency and Q for several filters. There may still be a need to tweak, but you get there faster.

Some consoles only allow a low-pass filter by stealing the highest EQ filter, turning its Q all the way down, then turning it on with the gain and adjusting its frequency. These can also be incorporated into presets, saving those encoder strokes as well.

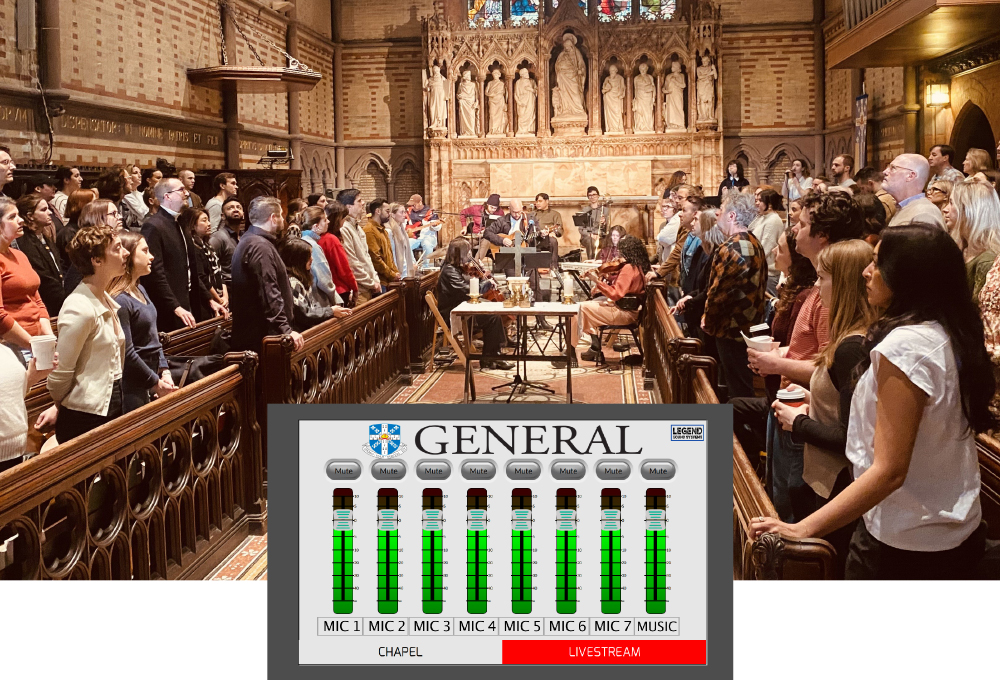

Similarly, GEQ libraries can be used for specific combinations of vocal mics and floor monitors that are used frequently. After investing the time it takes to carefully adjust one wedge with a mic, that setting can be quickly copied into the graphic equalizers for a number of mixes with the same mic/wedge combination. Self-powered monitors are typically very consistent, allowing settings created for them to work well on many other suppliers’ wedges. Giving them meaningful names like “MJF212wSM58” allows them to be saved for the next time that combination is deployed.

EQ libraries can also be used to adjust in-ear monitor equalization with individual musicians, allowing you both to explore making minor adjustments to their overall mix EQ to help their IEMs better match their hearing. By giving them meaningful labels, like “DaveIEM0915,” you can archive a record of daily IEM mix EQ settings in what can be an iterative process that gradually gets an IEM mix sounding better to that performer. You may even discover subtle changes to their hearing from the beginning of the set to the end, or from Friday night to Sunday night.

Obviously the same applies to effects libraries. I’ve heard very few reverbs that couldn’t benefit from a little parameter tweaking, including the EQ on their return channels. You might go ahead and tweak and load up the console with an entire assortment of application-specific effects from snare to fiddle to acoustic, so that when you want them, they’re ready to go, as long as you have channels to return them.

At a minimum there should be a generic vocal and instrument reverb in your file, patched from a pair of aux sends and ready to go into a mix. Then replacing them with exactly what’s needed can be quickly chosen from your custom effects library. When you save your entire console, all of these libraries are stored and carried on a USB key to the next gig.

Some consoles also allow making a preset out of an entire auxiliary send. One day percussionist Daniel de los Reyes told me his mix was a little off. I asked him when was the last show it sounded good to him, and he replied “Philly.” I was able to go back to my Philadelphia file, make a preset of his mix and paste it into the current file. Bueno, aquí estamos en Philly.