Recently I was asked to mix a live show on a console that could only be controlled via a tablet, and I found myself arguing quite strongly that a dedicated control surface was needed to do the job properly.

I have nothing against these types of mixers, particularly in situations where space is limited, costs are an issue or where it’s not possible to put a console out front. They can be very handy – but they’re no substitute for a proper control surface.

In fact, I’ve always been a big fan of the ability to remote control digital consoles using a tablet because it allows me to walk the room and make adjustments in a way that was impossible in the analog days.

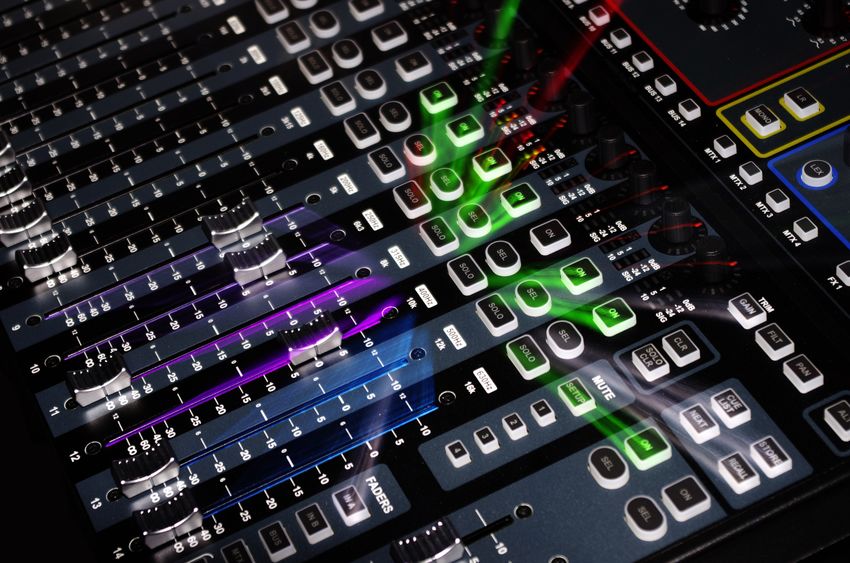

But a key difference between this approach and a mixer operated solely by tablet is that you still have a traditional control surface to return to. It will always be quicker and easier to line check and start to build the mix using a dedicated control surface. This situation got me thinking about the nature of live sound consoles and how they’ve progressed to where they are today.

Early Days

The very first electric PA systems were pieced together in the early 20th century out of technology invented for other reasons. For example, microphone and loudspeakers came from the telephone and tubes (for amplification) came from wireless telegraphy.

The main purpose of those early systems was to amplify and propagate the spoken word, the number of channels was limited (often just one), and they were usually controlled via large Bakelite knobs on the amplifier.

The advent of rock ‘n’ roll, the development of the electric guitar, and the need to perform in larger and larger spaces pushed the development of the PA system through the 1950s and 60s, channel counts gradually increased and amplifiers got bigger.

Very few venues had in-house PA systems, so bands tended to travel with their own or hired them locally. It was either set up on stage and operated by the band, much like a guitar of bass amp, or placed nearby and operated by a technician.

Typical equipment would be a simple mixer/amplifier such as the Altec Lansing 1567A (Figure 1), sporting a handful of volume controllable inputs, global treble and bass controls, and a master volume control. However, engineers and technicians soon demanded better control of the mix so they turned their attention to the studio.

Mixing consoles had already been established as the control surface of choice for recording and broadcast applications, but the design took a little while to coalesce into the form that we’re familiar with now.

A key milestone was reached in 1958 when EMI’s Record Engineering Development Department installed the first dedicated stereo mixing system at Abbey Road Studios in London, the REDD 17.

The legendary console, used by the Beatles and many others, is widely acknowledged to be the first console that established the template that all subsequent consoles would follow, namely a bank of input channels (in the unit shown in Figure 2, just eight) arranged in rows with a fader at the bottom and EQ controls above.

But the consoles employed in recording studios were unwieldy beasts resembling large, thick tables with two solid legs, they were clearly not suited to the demands of live sound.

So various companies started developing more compact and portable mixers, often building their own “home brew” models, such as the Brighton Sound “Buck Rogers” mixer (so called because someone said it looked like something from the TV show). Figure 3 shows it being put to use at the Groveland Festival in New York state in 1970.

Gathering Steam

Going into the 1970s, the design of analog consoles settled into the basic template of a bunch of input channels and a master section arranged on a near horizontal control surface.

Each channel typically featured, from top to bottom: gain, EQ, auxiliary sends, pan pot and a fader which were ordered that way simply because that was the order of the signal flow (with the obvious exception of post fade sends).

This neat design allowed channel strips to be narrow which enabled more channels to be fitted into smaller frame sizes increasing the channel count and creating the familiar sea of knobs.

A key part of the design of the analog console was the humble fader. Fader like controls already existed but much like the ones found on those pioneering REDD consoles they were actually rotary controls arranged side on and fitted with a lever which extended up to the control surface – this explains that characteristic curved path of movement.

The person who pioneered the use of the linear fader was Atlantic Records engineer and producer Tom Dowd. He observed that when mixing with knobs you could only manipulate two at once (i.e., one per hand) whereas he was a pianist who wanted to manipulate many channels at once, like the keys of a piano, so he found a company that made linear potentiometers, fitted them to the console in Atlantic Studios and the rest is history.