The Main PA

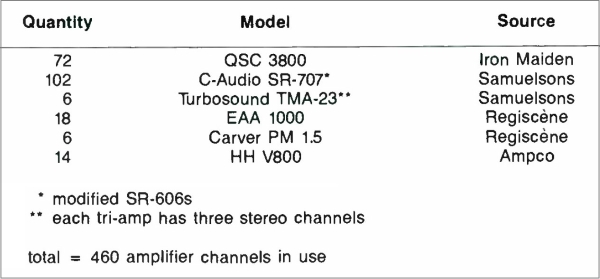

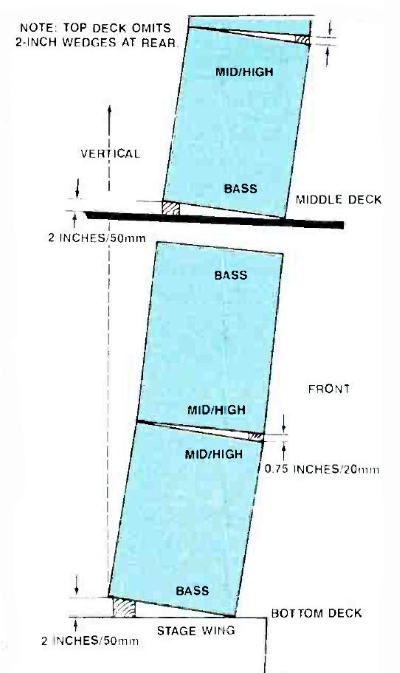

Table 1 shows the 460 amplifier channels in use on the two PA wings. These were divided between stereo amps, half-used stereo amps, and some TMA-23 stereo tri-amp units (a Turbosound market research product no longer manufactured).

Owing to the diverse sourcing and the differences in rental companies’ interconnect standards, the amplifiers needed very, very careful matching.

John Newsham from Turbosound and Julian Tether (then Samuelson’s chief technician, now working for Britannia Row) spent an evening religiously checking and correcting sensitivities and normalizing the polarity of every amplifier. Five more hours were spent adjusting the system grounding to reducing residual hum and noise.

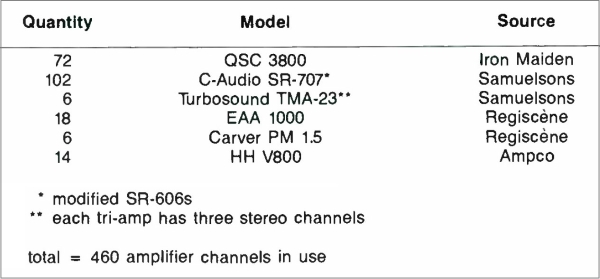

At Hall’s insistence, the 400-plus amplifier inputs were driven from a single BSS MCS series crossover.

This approach promised sonic coherence, but with incompatible amplifier racks supplied by four different companies, it also presented a nasty interface headache. Any failure would silence the main PA outright.

Stress on the crossover outputs was avoided by using BSS’s newly developed high-power line driver “booster” package, made to plug into the MCS Series crossover “mainframe.” It was first devised in association with Concert Sound to drive 200-plus amplifier channels at the Nelson Mandela birthday bash.

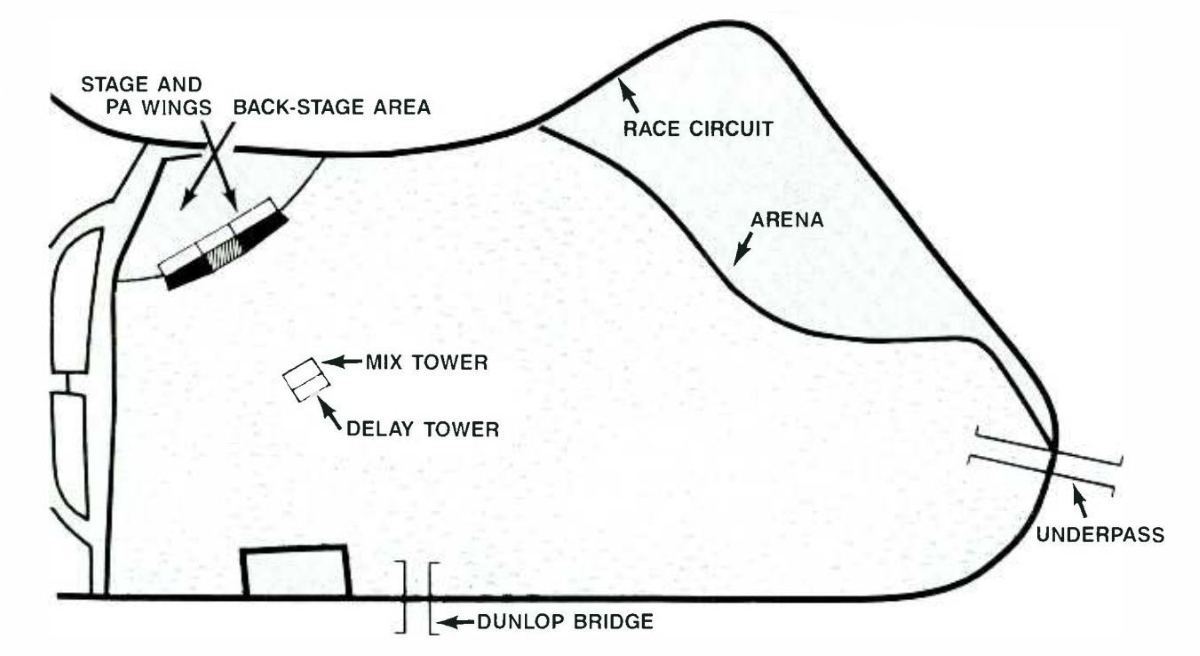

At Donington, two line drivers were placed at the stage end of the returns multicore. Figure 1 shows the general interconnect scheme. The main house system comprised 304 Turbosound TMS-3 enclosures.

The 72-foot stage wings had three tiers, each with 48 Turbosound enclosures in two rows, totaling 144 per wing. The remaining 16 were placed under the front of the stage, with a separate vocals-only mix to balance the plainly audible instrument amp stacks and side/drum fill monitors.

In the wings, the enclosures were stacked vertically: first, to gain the longest throw from the HF horn, and second, to close-couple the 10-inch mid drivers. On the ground, under the wings, were 60 Turbosound TSW-124 subwoofers, all arrayed for maximum coupling.

The TMS-3 is normally configured as a “medium-throw box.” Nevertheless, the capabilities of this giant array were clearly proved during initial sound checking by the PA’s clarity in a village two miles away.

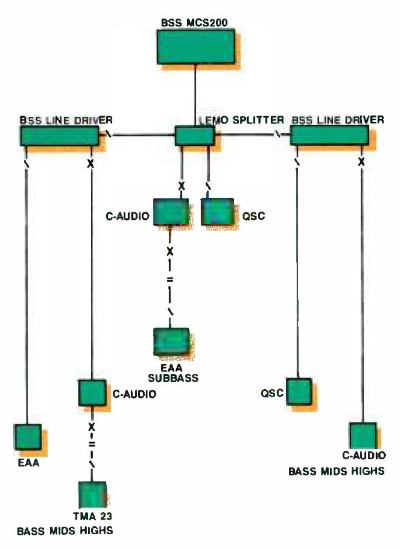

Flying the PA with the available scaffolding would have left a big gap between cabinets, ruining the coupling. Instead, every cabinet was tilted down (Figure 2), with lumber wedges acting as “acoustic compensators.”

Smaller wedges at the front fine-tuned the coupling between adjacent mids. Each tier was built 18 inches in front of the next, while the enclosures in each wing were arrayed in an arc, receding 10 feet at each “wing tip” to produce a pair of phase-coherent, virtual point sources. This allowed a relatively constant SPL to be maintained over the 60-meter span, back to the mix tower.

The small delayed PA, located immediately behind the mix tower, was rated at 50 kW. Because of the more-than-adequate bass and sub-bass projection from the main system, the delay tower’s low end was barely “ticking over” and it needed no subwoofers. Newsham said, “It’s not there to start the sound all over again, it’s there to give a gentle lift to the mids and highs.”

A look at the site plan (Figure 3) shows why: The land rolls away from stage-left into a bowl-shaped dip, then up into the main bowl and goes on rising gently to a ridge well beyond. Donington’s infamous “dog leg” means a major part of the audience is well off-axis from the stage. The delay array consisted of 30 MSI (Maryland Sound Industries) HF and 16 LF cabinets.

In addition, eight JBL long-throw horns at the top of the tower provided additional reach for the HF material. This array used the stage-right mix to “fill out” the stereo image 500 yards from stage-left. This is a technique first applied by Malcolm Hill, a UK PA rental company that has provided sound at Donington on past occasions.

The delay tower components were driven off their own crossover, through a Klark Teknik DN700 delay line. Stereo balance, horn aiming and delay times were first estimated; the delay was 1 millisecond per foot (1 ms/ft). With sound crew radioing back the results from a golf cart, the fine-tuning was accomplished fairly easily.

The Event

The warm day began with hazy skies and later clouded over. By 6 pm, attendance had reached 107,000. The inevitable rain came after nightfall, during Maiden’s set. The good side is that wet air seems to improve the transmission of sound.

After six years on the road and literally thousands of gigs to his credit, Hall (who’s been with Iron Maiden since the band’s first UK tour in 1980) said, “I don’t want a PA to sound like ‘big speakers.’ For me, it should be an extension of the stage, like it’s coming straight from the band. The PA should disappear. With this system, you can get the level without distortion that hurts your ears.” The philosophy is also supported by Motley Crue’s engineer Mark Dowdell.

Since the support bands’ sound peaked at between 6 and 8 dB below full output, the remaining headroom was more than comfortable. Under these conditions, the short-term rms SPL, monitored at the mixing tower, was 118 dB. It was 108 dB at the Dunlop bridge, 185 meters (more than 606 feet) from the stage, and nearly on-axis.

During Iron Maiden’s set, the short-term rms SPL was similar, but there were more dynamics; instantaneous peaks reached 124 dB at the mix tower, compared to 119 dB during KISS’s set.

What was achieved? Well, I believe that this is the first time a group of heavy metal bands have played (in the open air to more than 100,000 people) with enough power headroom to play loud and develop a peak-to-mean ratio (i.e., “dynamics “) of more than 10 dB — without stunning the limiters.

At the time this article was published, Ben Duncan was a London-based freelance writer.