Mixing is like driving – everybody does it, it gets you from here to there, and it seems like it’s been part of the culture forever. Driving is so pervasive that’s it’s easy to forget there are other ways of getting around.

Most of the time, though, it seems that we get behind the wheel simply out of habit. It’s only on those rare occasions when we deliberately walk to the store to pick up a loaf of bread, for example, that we remember there are other ways, perhaps better ways, of doing the simple things that need to get done.

It’s been said that when the only tool you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. This is particularly apt in the case of mixing for staged events. The bias toward mixing that’s pervasive in the industry is traceable in part to the large overlap in the designs of traditional recording, broadcast and live consoles, as well as to schools teaching audio (i.e., “recording schools”) that continue to focus on the art and techniques of the mixdown.

Other Ways?

Originating in broadcast and recording sessions involving multiple microphones, and refined in multitrack recording studios producing mono or stereo masters, mixing has become so entrenched in the industry and in the minds of many who dream of working in it that it’s almost as if no other way of working with sound is even remotely conceivable.

But of course it is. Mixing live sound is a relatively recent innovation. It wasn’t so long ago that virtually all pop music acts relied on instrument amplifiers and the acoustic output of the drum kit to fill a venue, the level of the vocals being brought into balance either via a relatively primitive house sound system or a couple of loudspeaker columns at the sides of the stage. Even the Beatles toured that way. It was only during their first tour of the U.S. and Canada in 1964 that the limitations of this setup became apparent, when their then state-of-the-art 100-watt Vox amplifiers were drowned out by thousands of screaming fans.

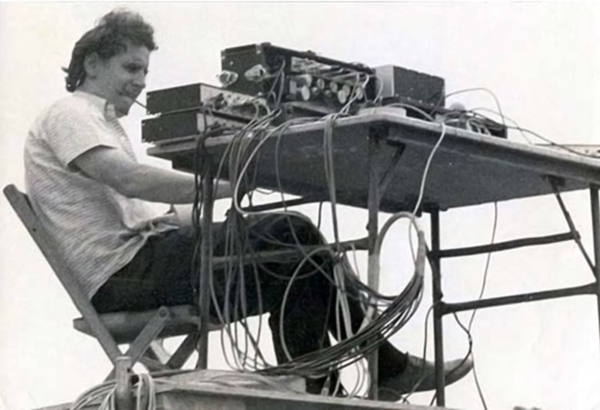

Sound reinforcement systems evolved rapidly over the ensuing decade, spurred by the needs of bands touring large venues and the staging of outdoor festivals, such as those at Monterey, the Isle of Wight, and Woodstock, where sound system designer Bill Hanley mixed sound for the three-day festival using several Shure 4 x 1 mic mixers.

Amplifiers and drums were miked along with vocals, and consoles soon grew larger as a result, offering more and more input channels. They evolved to include EQ, dynamics processing, and eventually an output matrix section providing the ability to route a variety of inputs to any or all of a series of outputs, a capability that had proven useful on Broadway and in London’s West End theatres.

One significant difference between rock concerts and live theatre, however, is that in concerts, the sound system is employed primarily to achieve high sound pressure levels throughout the venue, whereas in live theatre, the goal is to increase intelligibility. That line is often blurred in big, dynamic rock musicals, such as those of Andrew Lloyd Webber, whose sound designers evolved separate vocal and orchestra mixes, striving simultaneously for clarity in the voices and power in the orchestra.

When the deployment of delayed loudspeakers in the audience area became a staple of sound reinforcement systems in the late 1970s and early 1980s, it became possible to permit lower volume levels at the front of a large venue than would otherwise be required to provide sufficient reinforcement at the rear. For theatres, houses of worship, and corporate events, this is critical: if voices are presented at a level that is significantly louder than their natural level, any attempt to convey an illusion of realism goes out the window. As an added benefit, remote loudspeakers can be equalized to compensate for the inevitable acoustic deficiencies that lurk under balconies and in other less-than-favorable acoustic areas of a hall.