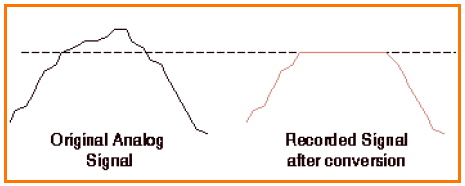

The Paradox of the Digital OVER. When it comes to playback, a meter cannot tell the difference between a level of 0 dBFS (FS = Full Scale) and an OVER. That’s because once the digital signal has been recorded, the sample level cannot exceed full scale, as in this figure.

We need a means of knowing if the ADC is being overloaded during recording. So we can use an early-warning indicator—an analog level sensor prior to A/D conversion—which causes the OVER indicator to illuminate if the analog level is greater than the voltage equivalent to 0 dBFS.

If the analog record level is not reduced, then a maximum level of 0 dB will be recorded for the duration of the overload, producing a distorted square wave.

After the signal has been recorded, a standard sample-accurate meter cannot distinguish between full scale and any part of the signal that had gone over during recording, it shows the highest level as 0 dBFS. However, a sample-counting meter can analyze a recording to see if the ADC had been overdriven.

This meter counts contiguous samples and can actually distinguish between 0 dBFS and an OVER after the recording has been made! The sample-counting digital meter determines an OVER by counting the number of samples in a row at 0 dB.

If 3 contiguous samples equal 0 dBFS, the meter signals an OVER, because it’s fair to assume that the incoming analog audio level must have exceeded 0 dBFS somewhere between sample number one and three.

Three samples at 44.1 kHz is a very conservative standard; on that basis, the recorded distortion would last only 33 microseconds and would probably be inaudible.

While this type of meter was sophisticated in its day, current thinking is that the sample-counting meter is only suitable for evaluating whether an ADC has overloaded.

Authorities now feel that meters which display the digital value of the samples and which count samples to determine an OVER are no longer sufficient for mastering purposes and should be used with caution during mixing. Their place is taken by…

The Reconstruction Meter: Even More Sophisticated As long as a signal remains in the digital domain, the sample level of the digital stream is sufficient to tell us if we have an OVER. However, signals which migrate between domains can exceed 0 dBFS and cause distortion.

This includes any signal that passes through a DAC, a sample rate converter, or is converted through a codec such as mp3 or AC3. During the conversion from PCM digital to analog or mp3, filtering within the converter yields occasional peaks between the samples that are higher than the digital stream’s measured level, which can be higher than full scale.

This next figure shows that contrary to what we might assume, filtering or dips in an equalizer which we’d imagine would produce a lower output can actually produce a higher output level than the source signal. B.J. Buchalter explains that:

“the third harmonic is out of phase with the fundamental at the peak values of the fundamental, so it serves to reduce the overall amplitude of the composite signal.”

“By introducing the filter, you have removed this canceling effect between the two harmonics, and as a result the signal amplitude increases. Another reason for the phenomenon is that all filters resonate, and generally speaking, the sharper the filter, the greater the resonance.”