Since Dolby began to expand the application of its object-based immersive audio format into live sound, the Dolby Atmos experience has been brought to venues ranging from the American Music Awards at L.A.’s Microsoft Theater to full performances by artists including Carlos Santana at the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino in Las Vegas.

Adding to that list this year was Maroon 5’s residency at Dolby Live at the Park MGM, the second-largest theater on the Las Vegas Strip. Divided among dates that kicked-off in late March, ran through the beginning of April, resumed in late July and came to a close in mid August, the hour-and-a-half shows were highlighted by the band’s expansive catalog of pop hits that served as the backbone of a set list of 20 songs.

The band (frontman Adam Levine, lead guitarist James Valentine, keyboardist PJ Morton, a trio of horns, backing vocalists, rhythm guitarist and keyboardist Jesse Carmichael, drummer Matt Flynn, and bassist Sam Farrar) guided crowds along a communal path that was part dance party, an homage to their late manager Jordan Feldstein, and a showcase of the theater’s immersive audio prowess.

Representing the third immersive residency Dolby Live has hosted recently (Aerosmith and Usher are the other two acts who have taken a turn in the room’s Atmos spotlight in recent times), Maroon 5’s efforts were carefully calculated, choreographed, and launched with no small amount of thought and effort.

New Frontier

“High expectations are placed upon any show undertaking a Las Vegas residency,” notes Maroon 5 system engineer Matt McQuaid. “Add the dimension of immersive audio to the equation, and you find yourselves pushing into a new frontier in terms of work flow and learning how to get better results. From the beginning, one of the overarching intentions of the band and all of us on the crew was that it had to be significantly better than stereo, or there would be no reason to do it all. We already had a great stereo mix that everyone was happy with, but the band gained an understanding of immersive technology in the studio and became intrigued with the format’s possibilities. At that point it was up to us to figure out how it would translate into the live domain.”

Joining McQuaid over the course of the production were front of house engineer Vincent Casamatta, Adam Levine’s monitor engineer David “Super Dave” Rupsch, and Marcus Douglas, who delivered stage mixes to the rest of the band. With Clair Global providing the control package in the form of a DiGiCo Quantum 5 console for the house, a DiGiCo SD10 for Rupsch, and a DiGiCo SD5 for Douglas, an Optocore network loop joined all three consoles, eliminating the need for a splitter and allowing a pair of DiGiCo SD-Racks with 32-bit I/O cards to be shared. With a UAD-2 Live Rack 16-channel MADI effects processor standing-in at the house joined by an RME MADI Converter and Pro Tools HDX recording system, Genelec 8050B nearfield monitors kept Casamatta informed on his own progress.

Left-to-right: Monitor tech/RF wrangler Clayton Johnson, System engineer Matt McQuaid, house engineer Vincent Casamatta, Adam Levine’s monitor engineer Dave “Super Dave” Rupsch, and band monitor engineer Marcus Douglas. (Photo Credit: Travis Schneider)

Lake processing was found in the drive rack along with an RME UFX interface, Rational Acoustics Smaart v8, a wireless measurement system from Lectrosonics and iSEMcon mics. The stage package – also drawn from Clair’s inventory – was comprised of mic selections from Shure, Sennheiser, Audio-Technica, Neve, and DPA. Radial direct boxes complemented the input approach.

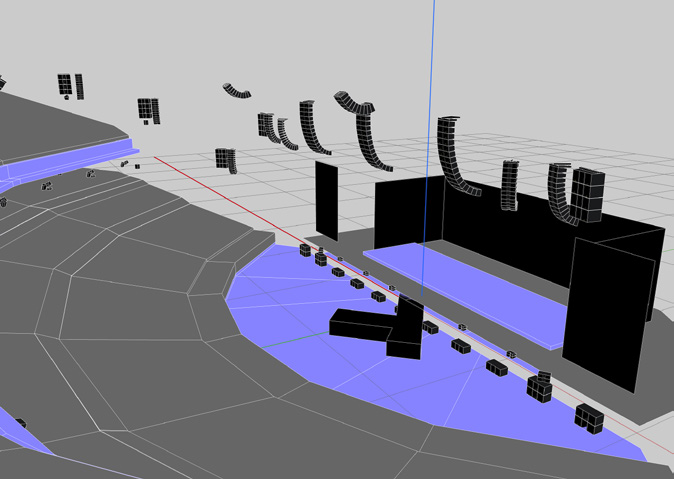

Designed, calibrated, and tuned by Dolby engineers specifically for the 5,200-seat theater (and further refined expressly for Casamatta’s use by McQuaid), the house PA is built around a sprawling collection of L-Acoustics arrays that spread even coverage throughout the room.

A true 9.1.4 system guided by Dolby drive rack components, including a Dolby Atmos Renderer, Dolby Live Panner App, DirectOut PRODIGY.MP, and an RME AVB tool serving as the interface to the house, the PA contains a wellspring of elements – among which are stage mains each comprising 16 K2 enclosures, wide arrays each using 14 KARA II and four SB28 boxes, KARA II outfills, 30 KS28 ground-stacked subwoofers, nine KIVA II frontfills, and a dozen KARA IIs and four KS28s in each side surround. Rear surrounds, balcony rear surrounds, balcony rear surround subwoofers, main floor overheads, and balcony overheads complete the package, once again using L-Acoustic cabinets including X12, KARA II, X8 and KS28 cabinets.

“As far as 9.1.4 systems go,” McQuaid says, “it’s similar to what you’d find in a studio, only on a much grander scale. This was the first time Vince and I took a stereo mix into immersive. We went into it with a lot of research and desire to learn with one of our main goals being to preserve the stereo mix underneath the immersive one for archival purposes at a minimum. The industry is still defining what immersive is and will be, and we wanted to have a hand in revealing the best practices possible.”

Dolby Atmos transcends Dolby’s traditional 5.1 and 7.1 surround technologies by adding a third overhead dimension. Free from the constraints of a traditional stereo rig, in a live sound application Atmos literally envelops listeners within an auditory “atmosphere,” as its name implies. Sound can arrive at your ears from any corner on any plane, creating an environment that more accurately represents how we perceive it in the real world.

All sounds within the Atmos realm are configured as audio objects, and are no longer restricted to their own channels. Every sound floats in space, and isn’t limited to horizontal or vertical movement. Horns can spatially be heard off to the left, and then to the right. A vocal can rise from the back of the room and then hover directly overhead. As an enhancement for a quiet, intimate acoustical song, sound in a large space can be condensed to an immediate area central to downstage that draws the crowd in close. Multiple reverbs can be spaced throughout a venue to imbue the space with a majestic size and scope, then be quickly brought back down to something transparent and extremely subtle.

When thinking of audio objects, remember that it is up to the audio engineer to decide what an object is going to be. Generally speaking, objects are components of your mix that deserve to be a unit, not necessarily just a single microphone. One object may be an entire snare bus, or a bass synth bus.

Retaining The Original

For Maroon 5, as they made the transition to immersive, the goal was always to retain the band’s original aesthetic and sounds. “Even in Atmos, at the end of every single night I still delivered the band members a stereo mix of the show,” front of house engineer Vince Casamatta relates. “Our tried-and-true stereo mix still runs underneath our immersive mix for that and other reasons, another being since we chose to retain a lot of our original audio aesthetic, it was nothing less than totally logical to not want to break apart all those individual sounds I had to work so hard to create in the first place.

“Doing so would have been detrimental, requiring more time to build everything up again after the fact. When this project began, our stereo mix was the guiding light, the benchmark by which everything going forward would be measured, and that which the final product had to exceed.”

That said, how does one even begin to think about mixing for an immersive show? Casamatta brought focus to answering just that question by creating a spreadsheet that broke out every single component of the Maroon 5 mix: Vocals, snare drum, kick, toms, synth keys, guitars, piano…

“I listed every single one of them,” he explains, “and while it may seem rudimentary, my goal was to strip the sound down to its spare and basic components. Drawing upon the stereo mix, all of these individual elements already had a dialed-in sound, so next I went and created an output for all of these elements, which then became the ingredients required of the immersive mix. Every ingredient was given a direct out. In stereo everything gets combined into a stereo bus that then feeds a processing network, and then the amps and speakers.

“The difference in an immersive world is there’s one more stop on the way to the audience’s ears, and that’s at a renderer, which in Dolby’s case is an interface with automation and time code that can be accessed with an iPad to offer a digital representation of all objects, and then spit them out of the network and amplifiers into a three-dimensional space.

“It’s like learning how to walk again in some respects, but it’s a great experience to go through because it makes you ask yourself what is a mix, what’s a good mix, and what are the individual components of that? It’s a back-to-basics moment on one level, but when you come out the other end you are on an entirely different plane.”

Once Casamatta broke out all his ingredients and created a show with all of his elements crafted and routed into the immersive platform, he placed the kick, snare, and vocals into the center of the room, and all the rest in the left and right corners of the space.

“At this point I was essentially listening to a stereo mix,” he adds. “I learned right away that if it doesn’t sound as good as it should, fix it immediately well before you start moving around in the three-dimensional space. Once it felt good in ‘stereo’, I started experimenting on what elements could move through the X-Y-Z axis, and when.”

He additionally discovered that if he was using parallel or bus compression, or treating busses together, he needed to create that same vibe on the individual elements. “Difficult, but not impossible,” he notes of the process. “Due to a greater field of view, mix elements no longer compete with each other for your ear. There is endless headroom and space, nothing left to hide behind. It really forces the issue of having your source tones, arrangements, and players all dialed-in within a perfectly flawless framework. There are discussions to be had with the artists onstage. Best to be proactive at every turn.”

Interesting Process

Monitor engineers Dave Rupsch and Marcus Douglas both agree that it’s been an interesting process watching Casamatta come up with various ways to substantiate his mix in Atmos.

“Overall, being a part of this production hasn’t brought about tremendous change in my world,” Rupsch says. “Adam did, however, spend a good amount of time in Vegas down on the thrust, which extends maybe 30 to 35 feet from the downstage edge. Compared to a traditional stereo show, there are seemingly arrays for the PA everywhere in this room, three of which are pointed directly down at him on the thrust. The bottom cabinets in each were pretty much parallel with the floor.

“He’s accustomed to hearing a little slapback in these kinds of situations, but the reflections and delays we were hearing coming from his microphone were pretty wild at first, comparable at times to the sound of a dubbed reggae record. Not when he was singing into the mic, but in the pauses between songs and when he was interacting with the crowd. I ended up putting a Neve 5045 Primary Source Enhancer in-line, and it calmed things down.”

Wedges – including Meyer MJF-210 cabinets and Clair CM14s – were used sparingly on the show for things like adding presence for onstage guitar. Shure PSM 1000 personal monitoring systems were the order of the day for everyone, while wireless duties were relegated to Shure Axient Digital AD4Q receivers using ADX2 transmitters. Long known for his allegiance to Shure’s SM58 capsule, for the residency’s second act beginning in late July, Adam Levine moved to a KSM-11.

Douglas began his career with the band in 2015 as a monitor tech, and steadily moved toward his current seat moving faders behind his DiGiCo SD5 for the band’s mixes. “The band mostly appreciates a house mix vibe in their ears,” he explains, “then a bit more of themselves on top. I run snapshots, but not too much automation. Waves plugins see some action at my desk, and I keep Waves Tracks Live at hand for recording, that’s it. I record tracks live primarily for virtual soundcheck.”

For the crew, being in the same venue every night had its perks, including much shorter commute times to work from their rooms at the Park MGM, down the elevator and to the theater. Crowds packed the venue, and included many dedicated fans who flew in just for the show.

In hindsight, Casamatta admits he wasn’t without trepidations when he, McQuaid, the band, and Dolby engineers including Bryan Pennington and Sebastien Pallisso-Poux set out on this immersive odyssey.

“I honestly didn’t know if it was going to be possible to make this happen the way we envisioned it,” he says on a parting note. “Audio is one of those things – the most important part of a concert, but no one really thinks about it. It’s why people go to shows, but it’s a given. We all know this inherently, and what’s so interesting about immersive is that it puts audio out in front of other aspects of a production maybe for the first time ever. It creates this aura of expectation among people when they go to a show. Now they are actually listening for the audio instead of just experiencing it. That in and of itself is a huge change.”