The many benefits of in-ear monitors include improved monitor and front of house sound, better pitch perception and timing, consistent monitor sound from one venue to the next, elimination of feedback, reduced vocal fatigue, complete mobility with wireless systems, lower audience sound levels and… the potential to reduce the sound exposure of performers and protect their hearing.

But there’s no guarantee of the widely touted hearing conservation for IEM users: “Your mileage may vary.”

Monitor engineers are motivated to provide performers whatever they want in their mix and many musicians consider IEMs like a studio headphone mix: dense, busy and exciting. While IEM engineers have control of a mix, performers have the final say along with control of the overall volume: the knob on their receiver pack. The musician has final authority on what’s in their mix and how loud their mix is heard.

What is “twice as loud”? It’s neither 3 dB, nor 6 dB – it’s more like 10 dB; 3 dB more SPL simply requires twice the power; 6 dB requires four times the power, while 10 dB uses ten times the power to sound twice as loud. This means that for IEMs to be twice as loud, safe exposure time is drastically reduced.

On the other hand, turning down just 3 dB can make the difference between safe listening and jeopardizing hearing.

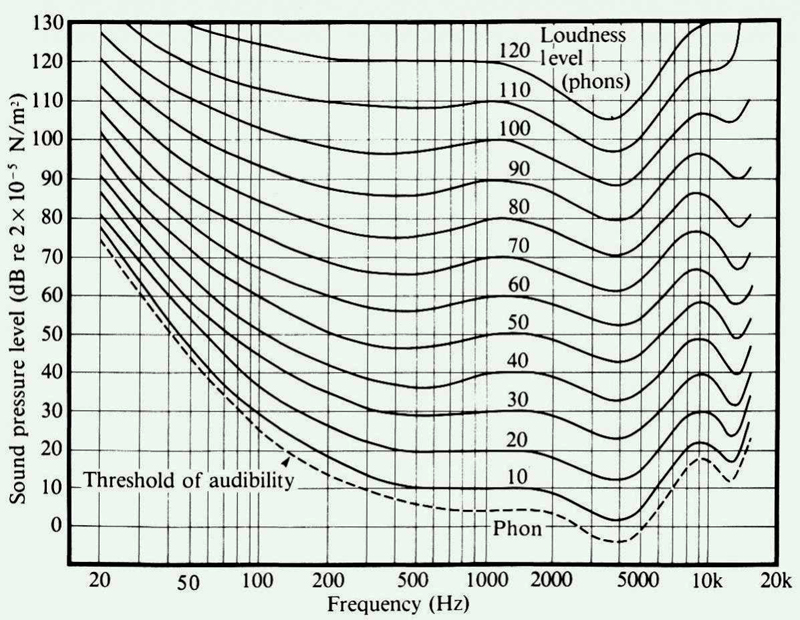

Why does louder sound better? Countless centuries of needing to hear a twig snap in the woods. We’re familiar with the iconic Fletcher-Munson equal loudness contours that show listeners perceive less lows and highs at lower SPL.

Older stereo “hi-fi” systems had “loudness” EQ filters to automatically turn up bass and treble at lower listening levels where the ear is more sensitive to midrange. As levels increase, perceived frequency response gets flatter – lows and highs are more easily heard.

Four-band parametric output EQ is standard on most consoles. Gently contouring an IEM mix with master EQ can improve it at lower volumes. Boosting 10k and 100 Hz while cutting 3k and 300 Hz can “open up” a quieter mix to be better heard at a slightly lower volume.

That said, the tendency always exists for performers to turn up over time, both because it sounds better and their ears get tired after an hour on stage. Louder is naturally “higher fidelity” to the human ear.

Level & Time

Any sounds of sufficient level and duration can cause hearing injury. Hearing injury is a function of not just volume, but of volume and time of exposure. It happens gradually over weeks, months and years. Once hearing is injured, it cannot be repaired.

How loud is your stage? Most veteran engineers mix with a sound meter at their console. There are several good iPhone sound meter apps. Log SPL ($1.99) is a full function meter with an analog display, digital readout and an FFT response; Sound-Meter+ ($1.99) is designed more like a sound dosimeter; the StudioSixDigital SPL Meter ($0.99) is a replica of the old Radio Shack analog meter many still keep on their meter bridges.

Sound meters can measure not just a stage, but also any loud environment, especially those occupied hours at a time: a rehearsal space, car, tour bus or sprinter van, and especially a flight. Airplane cabin noise is typically 85-90 dB and up to 105 dB on takeoff.

Window seats are 4 dB louder than middle or aisle seats. Seats forward of the engines are quieter than those further back. Earplugs, noise-cancelling headphones, and yes, IEMs can reduce exposure and risk of injury.

OSHA limits exposure of 95 dBA to 4 hours. Without ear protection, sitting in an aisle in the front can make a big difference on a cross-country flight. But how loud is it inside the ear canals while using IEMs?