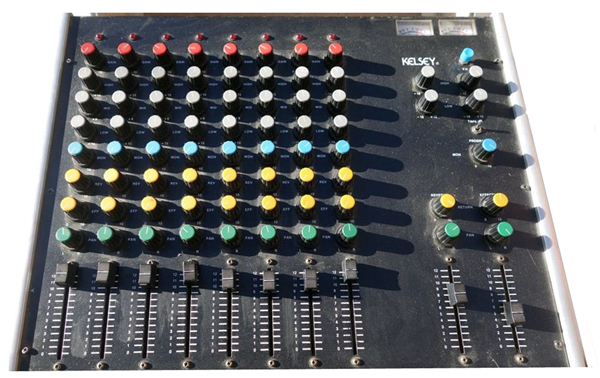

The first “big” mixing consoles I owned were a 12-channel Kelsey and a 16-channel Yamaha PM1000. The Kelsey saw the most use because the PM1000 weighed in at 110 pounds, and that was without the wooden case I built for it.

With a limited number of channels, buses and features available, I learned to be quite frugal when deciding what to mike onstage. For larger shows, the Kelsey sometimes served as a sub mixer for the drums and bass, feeding the Yamaha.

One day a buddy asked me to mix on his rig at a large outdoor jazz festival. It sported a 32-channel PM1000, and I was in heaven for two reasons. First, he didn’t ask me to help lift or move it, and second, I didn’t have to pick and choose what to put in the PA. With 32 inputs I could mike up everything onstage and still have empty channels.

Lacking, however, were monitor buses, but it was a problem easily solved back then by routing inputs to one of the four mix matrix buses and using those to feed stage wedges. Not as ideal as having individual aux sends on every channel, but musicians were aware of technology limitations and were happy to get more than one mix in those days.

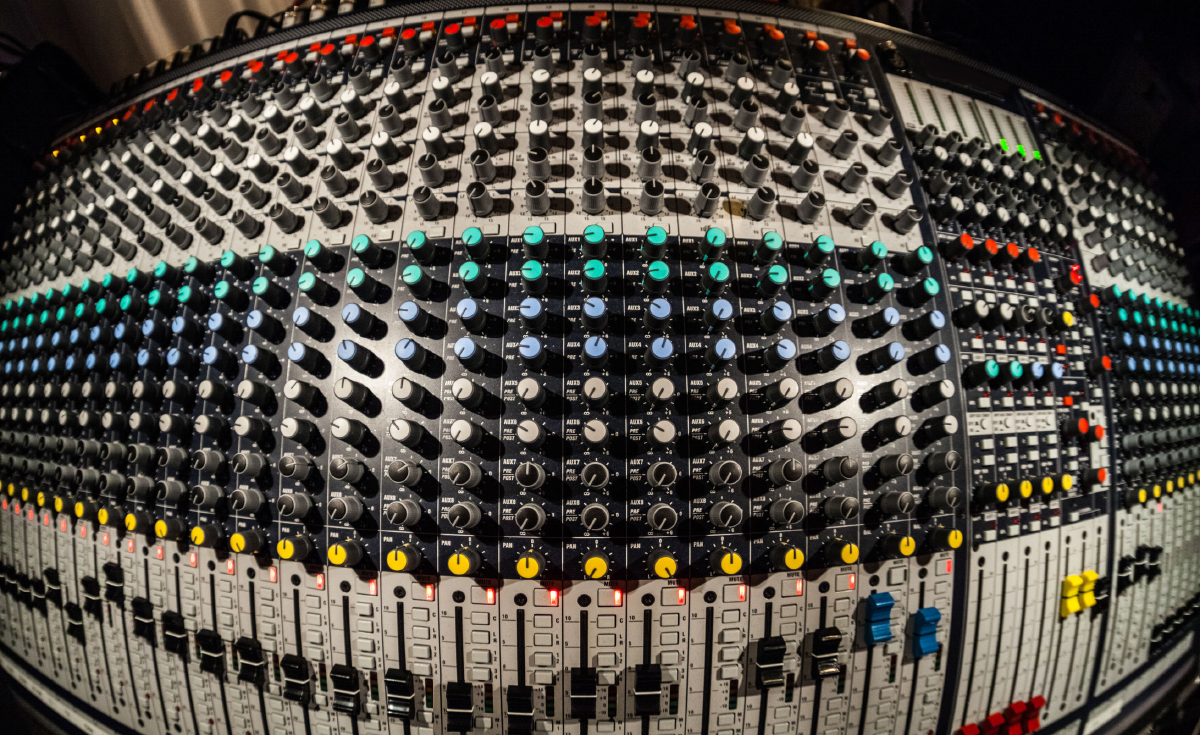

Fast forward to today. One of my small digital consoles offers 66 processing channels and up to 14 mono buses in a rack-mount form factor. With onboard GEQs, FX units, comps and gates, there’s no need to carry outboard gear, and it can be picked up effortlessly.

But as full-featured as these smaller boards are, bigger is often still better because clients always seem to need another feed or send somewhere, and there’s almost always extra inputs that show up at the last minute.

Regardless of the size of the console – or if it’s analog or digital – sometimes we have to be a little “creative” to get the desired results. Here are some things I do.

Regardless of the size of the console, sometimes we have to be a little “creative” to get the desired results. Here are some things I do.

Doubling Up

When running both front of house and monitors from the same console, it means that the monitors either share the same channel EQ dialed in for the mains (post EQ sends) or they do not get any EQ at all (pre EQ sends). This might not cut it for a picky performer or an acoustic instrument.

What I do is use a simple splitter box to send the microphone or DI to two channels instead of one. The first channel is for the house mix and the second (usually adjacent to the first) can be “dialed in” with an acceptable EQ for the monitors.

On smaller acoustic shows, I might place every input into two channels, effectively providing separate house and monitor consoles. If there aren’t enough splitter boxes handy, I can use a channel’s direct output to feed the second channel. On a digital console that offers channel patching, simply patch an input to more than one channel in the menu.

I’ve also used a second channel for singers who want a significant amount of effects in their monitors but don’t want to hear the effects when they’re talking in between songs. Sure, I could mute the FX masters, but on most of my consoles they’re on a different layer by default. Using the second channel for effects to the monitors, I can simply press the convenient mute button to stop the effects as needed.

It’s also easier to dial in a good mix of “dry” verses “wet” vocals in the monitors because I can simply send dry effects to the monitors from one channel, and then wet it up as needed with the second channel.

Another use for second channels is making a killer board recording. Many of us make recordings of live shows, and there are a lot of ways to do it. “Down and dirty” board tapes can be had by taking a copy of the main L+R outputs and sending them to a stereo recording device.

Newer digital consoles usually offer the option of recording a stereo feed to a USB drive, but the mix and some instruments may not sound “right” because they were equalized and balanced to be heard through the PA rather than a recording.

Sometimes all that’s needed is a good stereo board tape. Sure, you can set up a mix using an aux send, but this raises the problem of sharing the EQ with the house PA. Using second channels on instruments or vocals that have been “overly adjusted” to sound good in the house can result in a better recording because you can have control over difficult stage sounds as well as EQ directly for the recording.

Matrix Mixing

For years I carried around a line-level distribution amplifier in my rack because I was always running out of outputs on the corporate-type shows that make up the majority of my work. I might only need a few inputs but dozens of outputs for the main loudspeakers, delay and fill loudspeakers, as well as feeds to the venue for underbalcony fills, lobby systems, overflow rooms, onstage and backstage monitors, video and safety recordings, intercoms and dressing rooms, etc.

This is why I gravitate to consoles that have extensive matrix sections. In its most simple form, a matrix takes a selection of inputs (usually derived from the group and main output buses) and allows routing of those signals, complete with level control, to a series of outputs. Complex matrix systems offer the ability to choose from a variety of inputs, including specific channels or external sources, and may supply processing that includes EQ, compression, limiting and even signal delay.

A matrix adds a ton of flexibility to a console and gives the user a lot of easy solutions to routing problems, like adding a support act console.

While there are many ways to tie two or more consoles into a single PA, more than a few times I’ve simply patched the support act console into the external matrix input on the main console and fed the PA from both consoles through the matrix out.

Another good use for a matrix is creating mix-minus feeds. This refers to a program feed that has been remixed to exclude one or more input components. Sometimes the video people might want the program audio minus the playback audio they’re sending to front of house, or teleprompter operators want to hear the program feed but with less music. I can whip up a quick mix-minus by routing the various parts of the program through subgroups and into the matrix. Levels of each feed can then simply be adjusted as needed.

In corporate work, it’s sometimes necessary to provide audio feeds for remote meetings. I need the audio from the remote site in the PA, but don’t need to send it back to them. so I’ll create a mix minus the remote audio by using the matrix, and then add processing like leveling and compression before sending to the remote site.

More than a few times I’ve been mixing monitors from a smaller front of house board and have run out of aux sends. Using a matrix, I’ve set up side fill mixes as well as individual performer mixes.

Additional Pursuits

One great feature about larger consoles is, of course, more channels to use. I can employ back-up mics or run back-up lines without having to re-patch.

Ever wonder why there are two mics on the podium at high-level events? One is normally not on, used as a spare that’s already in place in case there’s a problem with the main podium mic. Simply un-muting the spare keeps the show rolling. It’s the same reason we place two lavalier mics on important presenters at corporate shows or on lead actors in theatrical performances.

Note: sometimes two different pattern podium mics are used, like a cardioid and supercardioid, with the mix engineer choosing between the two, depending on the person speaking.

Larger channel counts allow me to do some things normally not pursued when I’m running out of inputs. For example, instead of choosing between two overheads, or a single overhead and a ride cymbal mic, I’ll probably use two overheads and a ride cymbal mic on the kit. Same with snare drum. With enough channels, I often opt for a bottom snare mic to pick up the snap, capturing a better overall drum sound.

Extra channels can also be turned into an ad hoc intercom system. I place a mic at front of house, plug it into a spare channel and send it to a powered loudspeaker placed backstage via an aux send. A mic placed backstage is routed to a second spare channel, and by pressing that channel’s PFL button, I can hear the person backstage on my headphones. Not perfect, but when the intercom power supply loses its magic smoke 15 minutes before a cue-heavy show, you do what you have to do.

One more use for extra channels is “phantom mixing.” Ever get to the point where you’re satisfied with the mix and then a person walks up to FOH and tells you that they can’t hear their girlfriend, boyfriend, wife, child, niece, etc.? A quick twist of an unused channel knob and a sincere “Is that better?” usually gets them out of your hair…