Reshaping dynamic envelopes

Just like compressors, gates are also employed to reshape the dynamic envelope of instruments, mainly of percussive ones.

We can say that a compressor operates on a transient (once it overshoots the threshold) and on what comes shortly after it (due to the release function).

A gate operates on both sides of the transient (essentially the signal portion below the threshold). Yet, a gate might also affect the transient itself due to the attack function.

A part of adding punch is achieved by shortening the length of percussive instruments. Typically, the natural decay that we try to shorten is below the threshold, which makes gates the favorite tool for the task.

It is a very old and common practice – you gate a percussive instrument, and with the gate release (and hold) you determine how punchy you want it. Just like with compressors, we must consider the rhythmical feel of the gating outcome.

As gates constrict the length of each hit, the overall result of gating percussive instruments tends to make them tighter in appearance.

Figure 11 demonstrates this practice. The threshold is set to the base of the natural attack and above the natural decay.

The range would normally be set moderate to large. The release and hold settings determine how quickly the natural attack is attenuated (with longer settings resulting in longer natural decay).

If we only want to soften the natural decay, not shortening it altogether, we can use smaller range settings. Gates are often employed to add punch to percussive instruments.

We can also accent the natural attack, accent transients, revive transients or recon-struct lost dynamics using a gate. This is normally done by setting the threshold some-where along the transient and dialing a very small range so everything below the threshold is mildly attenuated.

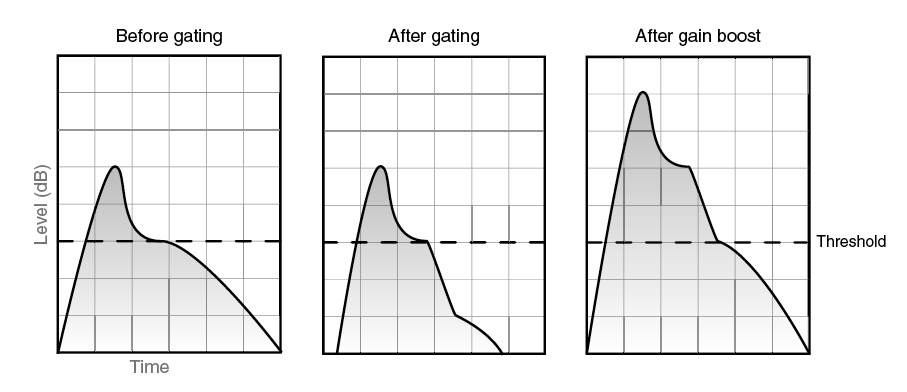

It is also possible to boost the output signal, so the transient is made louder than before, but everything below the threshold returns to its original level. Figure 12 illustrates this.

It is worth noting that the threshold in Figure 12 was set higher than the base of the natural attack. Had the threshold been set lower than that, the gate operation would most likely alter the dynamic envelope of the snare in a drastic, unwanted way.

Figure 13 illustrates this, which essentially demonstrates why this specific application can be somewhat trickier to achieve with a gate than with a compressor.

We said already that a gate’s attack and release functions tend to be more obstructive due to their typical short settings.

While on a gate we would dial both fast attack and release for this application, on a compressor we would dial longer, less obstructive settings.

One outcome of this is that when gates are employed for this task, the results tend to be more jumpy than those of a compressor. For these reasons, the gate’s range is often kept as small as needed, and look-ahead is employed.

This is the continuation in our series by Roey Izhaki on gates. Additional segments within the series are available here.

To purchase Mixing Audio: Concepts, Practices and Tools click on over to the Focal Press website.

Roey Izhaki has been involved with mixing since 1992. He is an academic lecturer in the field of audio engineering, gives mixing seminars across Europe at various schools and exhibitions, and is currently lecturing in the Audio Engineering department at SAE Institute, London.