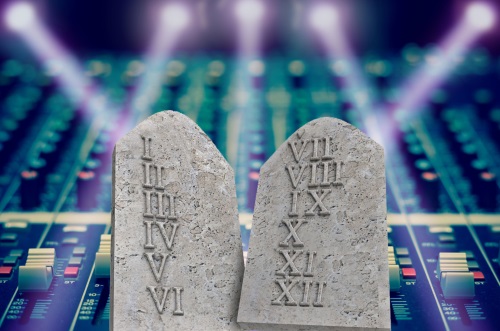

Over the years that I’ve been teaching live sound, I’ve developed a list of commandments (or points to live by) to pass on to my students to help them as they take their first steps into the scary and exciting world of professional audio.

While these points are aimed at those starting out in small venues, they can be applied equally well across the entire width and breadth of events to help ensure they run smoothly and that the experience is rewarding for the performers and the audience alike.

1. Be nice – friendly, courteous and professional.

Greeting musicians as they arrive and introducing yourself is a great way to get the day started on the right foot; it puts people at ease and creates a positive first impression. Being courteous and friendly throughout the day maintains a productive working environment that helps everything run more smoothly. It’s no coincidence that performers who have faith in the professionalism of the sound engineer are more relaxed and perform better as a result.

2. Stick to the schedule.

Live music, by its very nature, can be chaotic. It invariably involves multiple performers who need to be coordinated in order to ensure the whole event runs smoothly, and in the absence of a stage manager, the task of keeping everything to schedule inevitably falls to the sound engineer.

This can be a challenging task (often compared to herding cats) but keeping everything on track can help to avoid the stressful situation where you’re trying to claw back precious minutes in the changeovers. Nobody enjoys having their set cut short so the event finishes before the curfew, and nobody wants to be the person who has to tell the headliner that this is the case.

3. Always carefully set and re-check input gains.

Sound checks tend to be a boring time for musicians; they hang around until they’re called to the stage and then in turn to play their instrument in isolation so that you can start to shape the individual sounds and begin the process of building the mix. It can be quite a repetitive and mundane process, so it should come as no surprise that musicians tend to play softer in sound check than they do when the adrenaline kicks in for the show itself.

As a result, it’s always wise to take this into account when setting gains, allowing plenty of headroom for increases in the dynamics of the playing – and always remember to re-check the gains when the show starts. It’s particularly important on any inputs that utilize dynamic processing, such as gates and compressors, because any changes in the level of the signal will affect how the processing works.

4. Use equalization (EQ) only where necessary.

One thing I’ve noticed is that whenever folks are let loose on a mixing desk for the first time, they seem intent on operating every single control available, particularly when it comes to EQ. They dive into the EQ section with two hands, applying all manner of filters and tweaking them endlessly.

While this approach might get the results, it’s always better to step back, listen, and evaluate what EQ is required – if any. I’ve always been a strong believer that putting the right microphone in the right position often produces the desired sound at the source, without requiring much in the way of additional processing (except possibly a touch of high-pass filter, which I’ll address next). Overuse of EQ can result in a messy mix and can also increase the risk of feedback on higher gain signals.

5. High-pass everything.

The high-pass filter (HPF) is one of the most valuable tools at your disposal. Most sources on a stage have the ability to produce energy below the range of frequencies required to adequately convey their core sound, so it makes perfect sense to trim them using the HPF.

When multiple instruments are producing energy at similar frequencies masking can occur, and when this happens, the temptation is to turn up the obscured instrument, but that only makes the problem worse.

I find it helpful to think of the mix as a “frequency jigsaw” where the goal is for the pieces to fit neatly together without overlapping. High-pass filtering can also help minimize the proximity effect inherent in directional mics, as well as reduce unwanted leakage from bass instruments across a stage with multiple mics.