Distributed Boom

Subwoofer deployment is another aspect to consider. The goal is for them to blend in with the output of the tops. Subs usually operate in a general frequency range of 30 to 110 Hz, which means wavelengths of about 10 to about 35 feet long.

Anything within one-quarter (1/4) of the wavelength in distance can affect the output, including floors and walls (a.k.a., boundaries), as well as additional subs stacked next to each other.

If we suspend a sub in the air, the output emanates in all directions, and if it’s more than 8.75 feet away from any surface (a one-quarter wavelength of 30 Hz or 35 feet), it does not get any gain in output from a boundary.

Place the sub on the floor (called half-space loading) and there’s an additional (theoretical) 3 dB of output because the energy that would have traveled down is now reflected up from the floor.

By placing a sub on the floor next to a wall (quarter-space loading) we add 6 dB more output, and moving it to a corner (eighth-space loading) adds 9 dB. (While this looks great on paper, in the real world the numbers won’t be that high because of interference from the boundary and the acoustic space.)

Now, place the sub one-quarter wavelength from a rigid wall, and it’s output will bounce off the wall and return to the sub, making it about one-half wavelength, with the phase about 180 degrees from the original signal. This results in destructive cancellation. Depending on distance from a boundary and the pitch of the signal, frequency response is affected.

Most subs radiate energy in an omnidirectional pattern, and this pattern can be modified by other subs operating nearby. A common approach is placing subs at the left and right sides of the stage, which can result in a “power alley” where the bass frequencies from each side combine and add power. The audience seated in the middle hears the output from both sides equally and gets a lot of low end. However, as you move off center, phase and time delay issues cause cancellations, and for those off to the sides or in some of the null zones, the low end can be weak.

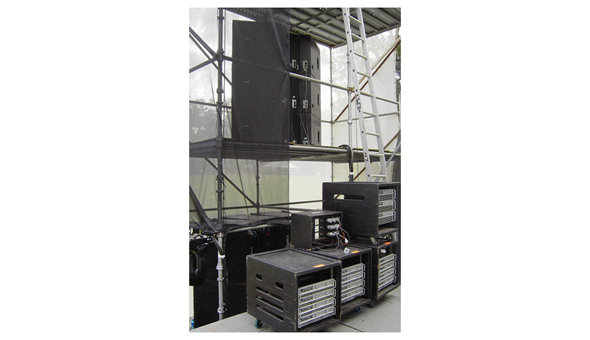

A center location with one or more subs can prove ideal for achieving a smoother coverage pattern, but this method may result in putting too much bass back onto the stage unless cardioid cabinets or configurations are implemented. Center flown sub arrays are popular for installs, especially in theaters and houses of worship, but not so much for live events, largely due to logistical considerations and related issues.

Cardioid and end fire sub arrays can be made from multiple cabinets offering directionality and pattern control while producing less sound behind the subs. These work pretty well in keeping bass off the stage and out of backstage areas.

A popular cardioid approach involves stacking the subs on top of each other, with one cabinet (usually the middle one in a stack of three) reversed to point to the rear. Pattern control is attained by using delay so that the signal at the rear is 180 degrees out of phase with the front-facing cabinets, canceling much of the sound. Several manufacturers offer cardioid subs with either rear-facing drivers or vents to help cancel out sound behind the cabinet.

End fire arrays consist of multiple cabinets that are aligned in a row, arranged one in front of the other with all pointing forward. All of the subs are delayed in relation to the rear-most cabinet, making it possible to project powerful, directional bass over long distances.

Finishing It Off

One more key is optimizing a system for the room or location. This is generally called system tuning, and it involves both our ears and a measurement rig utilizing quality, purpose-designed software such as Smaart from Rational Acoustics. It shows us the input signal, compares it to the output signal, and even reveals how a room is affecting loudspeaker output. It’s also easy to see things like frequency response, phase response, delay and more, and it’s all information that can help us “dial in” a system.

The final step is back where we started: listening. Once a system is set up and the coverage is on target, play known tracks and listen to the tone. (Also double check the coverage.) At this point, I make as few changes as possible, then set up a mic at stage center pointing straight up on a stand. In this process, first verify that the mic channel EQ is flat. Next, bring up the input of the mic until a bit of feedback occurs, and then use the main EQ (graphic or parametric if available) to pull down the frequency that’s ringing down until it stops.

Push the fader up again until another frequency rears its head and remove it. Do this until multiple frequencies start to ring together, or there’s plenty more headroom in the mic than needed.

Play tracks again and listen to see if the music still sounds good. If I’ve hacked the EQ to death trying to get rid of feedback I start again, but this time using the channel parametric to get rid of a few frequencies.

While all of this seems like a lot of work, it’s essential to the craft and our role of audio professionals. We owe performers, audiences and our colleagues nothing less.