Power Issues

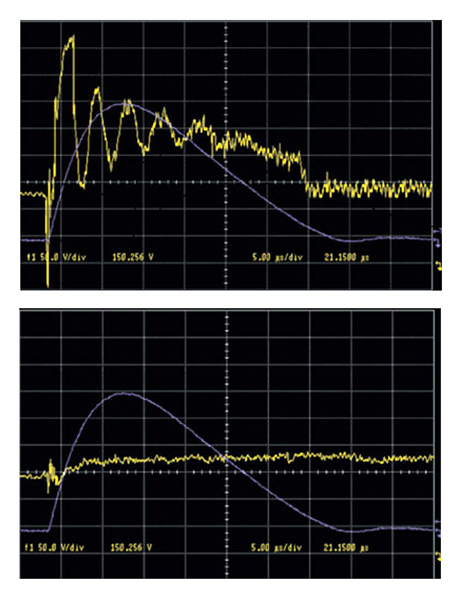

Power surges occur for a variety of reasons. One common cause is when a million or so watts of lighting is suddenly blacked-out at the end of a scene. The resultant voltage swing, especially under generator power, can be enough to fry a good portion of the sound system if the components are not otherwise protected.

Carefully check the power distro. If it does not include built-in surge suppression, some form of protection should be added in the branch circuits. There are numerous types of voltage regulators, surge suppressors, and power line filters available to suit most any need, from a small club system to a massive stadium concert rig.

Something I first witnessed and participated in – totally new to me at the time – was a Full Power Test at the 1988 Democratic National Convention, held in Atlanta at the Omni Arena. I’d worked in numerous arenas and stadia for rock ‘n’ roll, and power-wise, I just went with the flow.

But the seriousness of a political convention demanded an all-day comprehensive test. This meant that everything attached to building power – everything – was powered up and ordered to draw maximum current for eight hours. The result was that a few weak links were identified, including some faulty circuit breakers in the building subpanels, and were fixed before potentially wrecking havoc during show time.

It can be very expensive to provide full redundancy of a power distribution system on a large show. Multiple megawatt generators and their human attendants don’t come cheap. But when the event is of such importance that there really is no other choice, having redundancy becomes the only choice. Transfer protocols need to be carefully orchestrated, unless the “Gennys” are capable of synching to the grid, which is technically possible but not a normal feature of portable power plants.

If the system is powered from only one source and the power source fails, it nonetheless makes good sense to utilize an uninterruptable power supply (UPS) where the “brains” are, i.e., the house and monitor mix positions (assuming digital consoles). Though a power failure may bring the entire system down for the count, at least you’ll be able to save the console and effects settings, and hopefully avoid the additional delay of a reboot when the power is restored.

Smart Strategies

Though a serious failure might never happen during a show, if you’re adequately prepared it will be a minor problem instead of a major disaster. To begin with, map out every piece of gear that comprises the system on paper or electronically. Think about what will happen to continued functionality when each piece fails, and devise a plan that establishes what you will do about it. It should be in written form so that others can study it.

Obviously, the console is the central part of most systems and overridingly the most important. A simple and inexpensive contingency plan is to keep a compact backup mixer next to the big one, perhaps 16 to 24 inputs, but maybe as few as 6 to 8 for a small event.

Using solidly built Y-cords or a transformer splitter, parallel the most important signal sources to the backup mixer. Typically, these will be SA (stage announce), lead vocals, lead and rhythm guitars, bass, a keyboard feed, and a few mics from the drum kit. You might also take stems from the stage if available from the monitor console. But don’t rely on stems alone; if the house console fails and is interconnected in any way to the monitor console, a failure mode in one might affect the other.

Lastly, if there’s an OB truck involved, by all means take stems from it, because it’s quite possibly running from a separate power source. In fact, take a 30-amp power feed from the same source, if you can, as a backup to FOH power in case of an interruption.