If you’ve ever been on a large gig where the primary sound system failed, even if just for a short period, you’ve probably sensed you’re at risk of being on the wrong side of an impending riot. Audiences get restless, to say the least. This is an extremely high-stress position to be in.

If you’re the go-to technician expected to restore service, the rapidly elevating tension makes it tremendously difficult to troubleshoot the problem with each passing half-moment. It isn’t pretty, and it’s not without some very real danger to audience members, the crew and the performers – not to mention your career and the credibility of the equipment suppliers and manufacturers who have gear on the show.

The overriding guideline is simple: don’t put all of your cookies in one lunchbox. Anything that is indispensible in the signal chain will fail at some point in time. This includes that slick new mixing console, the loudspeaker controller(s), outboard equalizers, compressor/limiters that are on the master output bus (not to be confused with the tour bus), digital snakes, and every other device that you rely upon to keep sound waves emanating from your loudspeakers. And yes, at some time or other the tour bus will probably break down too, but that’s another story.

Amplifiers. Redundant amplification reflects most normal conditions. Almost any show, other than the very smallest, will employ multiple amps and/or multiple powered loudspeakers. Here’s an idea to consider: modern amps, even the bargain-priced variety, are so much more powerful than those of yore it makes good sense to standardize the amplifiers in your racks for low frequencies, mid frequencies and high frequencies, rather than selecting different power levels for each frequency band.

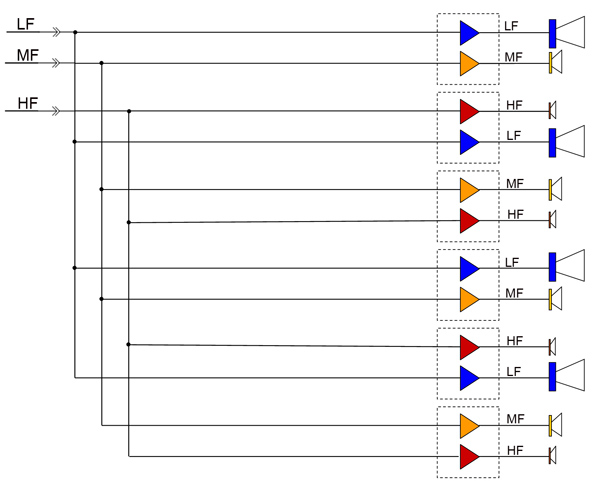

The amps can then be circuited so that one unit can power LF and HF; another LF and MF; another MF and HF, and then repeat as needed (Figure 1). Doing so offers three distinct advantages: First, if an amp fails, only a section of the system will go dark, rather than an entire bank of LF, MF, or HF drivers.

The second advantage is that the amplifier’s power supply, which is typically common to both channels in most two-channel units, will not be stressed as hard as it would be if both channels are only powering LF, because LF normally requires a lot more power than MF and HF. Headroom and maximum available power to the LF load will be improved, and with the lower overall demand on the power supply, reliability and longevity will increase.

The third reason is that you’ll only need one amp model for spares, rather than several. While there is a cost penalty to configuring a system this way, the collective benefits may very well outweigh the added expense.

Processors/Loudspeaker Management. Unlike amplification, redundancy in loudspeaker management systems is not always common practice. The deployment scheme is often intended for convenience and modularity, instead of ultimate reliability.

As a starting point, more than one loudspeaker controller should always be present, ideally interleaved with at least one other. This way, if a unit fails, only a part of the system will be affected, not the entire left side, center, or right side (the same concept is equally applicable to delay and fill loudspeakers).

Better still would be a controller for every amp rack, networked together to ease adjustability. However, not all loudspeaker controllers can respond to a common, master command. Making individual adjustments on a dozen or more controllers, such as EQ changes, is a time consuming and error-prone prospect, even if copy and paste among separate units is a provided function. It also means that you won’t be able to grab one control and change it in real time to hear the results, which makes it highly problematic to provide a speedy and uncompromised system tuning.

In such cases, it’s mandatory to use a master controller for room compensation and real time system adjustments, allocating the individual controllers in the racks for crossovers, driver protection, and other fixed loudspeaker compensation. But that leads us back to the “eggs in one basket” issue.

When using a master controller for EQ or as a master bus limiter, a second identical unit should always be employed, even if only two channels are needed. Run the left output through one unit and the right output through the other, leaving an open channel on each that’s pre-programmed and ready to take over for the other unit if it were to fail. If the system has additional zones, a similar principle should be followed.