6. OK, how do we spot these crews?

Apart from the obvious issue of having one of them land on or near one of the frequencies you’re using, they might pop up on a spectrum analyzer. However, for that to happen, you’d need to be scanning the whole width of the spectrum you’re occupying and be aware of all of your own transmitters. This can work if it’s a limited amount of spectrum, say 20 MHz for six wireless mics and six IEMs, but at the events I work we’re usually talking about at least 200 MHz and hundreds of frequencies.

This is why I’m a big fan of scanning in a much higher frequency range: visible light. That’s right, often the best chance of spotting these folks is keeping our eyes open and looking around. After a while, we start noticing different signs of them being present.

For example, if you see a heavy-duty tripod with no camera on it, it’s a pretty sure bet that a crew is nearby doing a “hit” (as they call it). Other times, you’ll see the tripod, a blue Cordura bag with a camera in it, and a well-dressed person standing around keeping an eye on the gear – while their camera person is parking the SUV.

Another tip-off is a camera with two closely spaced antennas on it. Shown in the photo that opens this article (top/right of this page), these two small whip antennas are the UHF Rx antennas. You may also see two other antennas on the back, which are for a wireless camera (video) signal. Of these two, the large rod antenna is the camera signal transmit (the picture), which operates in either the 2 or 5 GHz range, and the “rubber ducky” antenna on the back is the data or “paint” control for the camera (so it’s a receive antenna), which is in the 450 – 470 MHz “walkie-talkie” band. Note that typically we don’t need to be concerned about the last two, and that it’s very common to see cameras with those two antennas but without the UHF microphone receiver.

7. So, once we’ve spotted them, how do we deal with them?

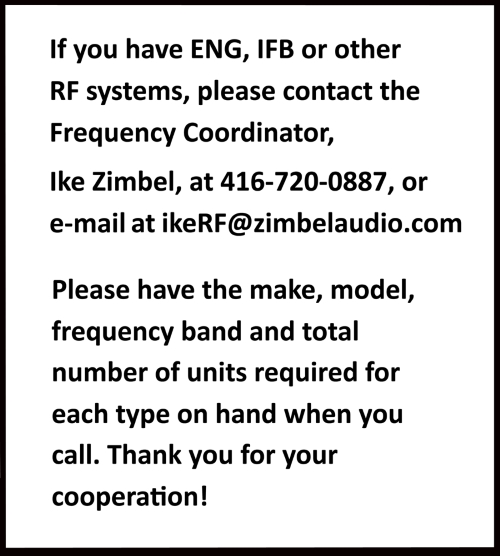

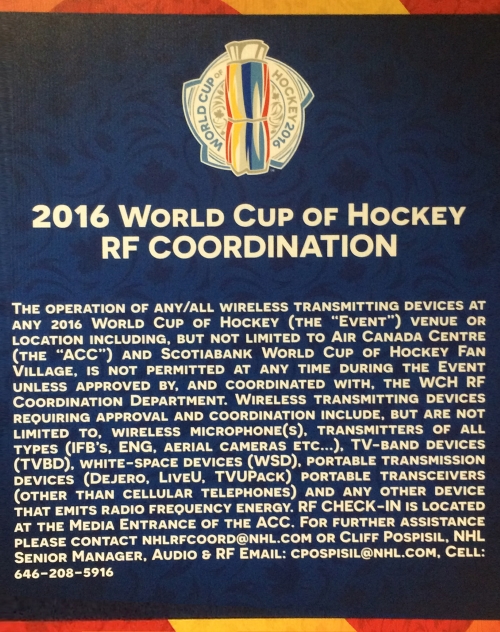

Once again it depends on the event. For example, when I’m working a National Hockey League (NHL) outdoor hockey game, the league mandates that it has complete control over all wireless devices in use. In this situation, I have complete authority to A) ask what frequency a crew is using, and B) coordinate a new frequency and verify that the crew has switched to it and remain on it. I typically have the same leverage at political events.

In contrast, last summer at a four-day festival at a public square in downtown Toronto, I had virtually no authority to ask anyone to change their frequency while they were at large in the square, so the job became more of an “observe and report” scenario. I would approach the crews, find out what frequency they were on, check it against my coordination and then if necessary, work around it.

This situation does change somewhat if the crew decides to make use of the media risers provided by the event organizers (in this case, the city of Toronto). Then, I have authority. However, an important thing to note is that all professional video cameras have audio XLR inputs on them, so the best course of action is to explain the RF situation and request that they use an XLR out of the media pool feed provided on the riser.

Lately, I’ve begun requesting that the PA supplier provide plenty of XLR cables with the pool feed so that no camera person can use the old “Oops, I didn’t bring a cable!” dodge.

And dodge they will. I’ve found that while most of the ENG/EFP folks are cooperative and even appreciative of being given a frequency they can call their own, there’s still a certain number that try to talk or walk their way around it. There are a variety of reasons why, the most common one being that they’re always in a rush to get in, do their hit, and get back in the SUV to go to the next one.

Other reasons can be that they either don’t like to, or don’t know how to change frequencies, and/or that they’re assigned frequencies at the station that they’re expected to stick to. (These are usually marked on the camera, sometimes incorrectly. On several occasions, I’ve been asked to change a frequency back to the assigned one after an event, which I always do).

If they demand to know why they need to change the frequency, I often respond with, “Well, if your news report turns out to be that the star’s microphone failed during the performance, let’s make sure that it wasn’t your mic that caused it to happen in the first place!”