Scenario 2

You’re the stage manager at a sports arena, where a soul diva is about to sing the anthem. On your left hip you’re wearing an RF intercom pack programmed to transmit on 620.000 MHz.

Standing to your left and looking lovely and focused, the diva holds a wireless mic tuned to 610.000 MHz in her right hand, at her side. And she’s wearing an IEM pack on her back tuned to 630.000 MHz.

You reach down, key your belt pack and tell the folks in the control room “I have the package, she’s ready to go.” As you do this, her hand shoots to her ear and a look of alarm passes over her face.

You key your intercom again: “Hold a minute, there’s a problem.” The diva looks at you – there was that noise in her ears again!

I’m sure you get the picture by now. Your intercom Tx and her wireless mic are producing an intermod product that is landing on her IEM frequency – but only when you key your intercom to talk, and possibly, only when she has the mic by her side. You can’t scan for that, but you could have predicted it with a frequency coordination program.

So what does a coordination look like? Well, for starters, it takes a computer program to sort out all of the math. Setting that aside for a moment, a coordination starts with a list of all wireless frequencies to be used. This includes:

A. All known local frequencies in use, including local UHF DTV stations (and VHF if applicable), and venue specific RF systems like the house intercom and hearing assist systems.

B. All wireless systems for the production, including microphones, instrument wireless and IEM for all acts on the bill, as well as any RF intercom system(s).

C. Any additional wireless systems on site, such as intercom for the video crew and ENG for local news outlets covering the event. The pre-coordination list should include the make, model, frequency band and quantities of all of the above.

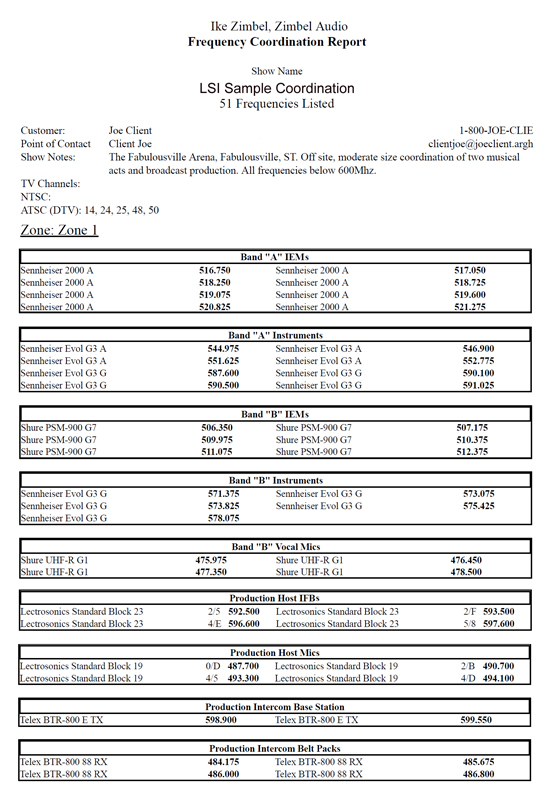

As an example, here’s a list for a small TV production with two musical acts, and to add to the challenge, I’ve allocated every channel in the spectrum below 600 MHz to give you an idea what the future holds.

Act “A”

Vocals: 6 x Shure UHF-R, J-5 range (578—638 MHz)

IEM: 8 x Sennheiser 2000, A range (516—558 MHz)

Instrument RF: 4 x Sennheiser EW-300, A range (guitars) (516— 558 MHz); 4 x Sennheiser EW-300, G range (bass, sax) (558—626 MHz)

Act “B”

Vocals: 4 x Shure UHF-R, G-1 range (470.125—529.875 MHz)

IEM: 6 x Shure PSM-900, G-7 range (506.125—541.875 MHz)

Instrument RF: 5 x Sennheiser EW-300, G range (558—626 MHz)

Production

1 x Telex BTR-800 base station (two frequencies) (Tx) “E” range (518.100—535.900 MHz)

4 x Telex BTR-800 belt packs (Rx) “88” range (470.100—487.900 MHz)

Host Mics

4 x Lectrosonics HH in Block 19 (486.400—511.900 MHz)

Host IFB

4 x Lectrosonics T4 in Block 23 (588.800—607.900 MHz)

Off Air TV

Ch-14, 24, 25, 48, 50, all DTV.

I’ve taken the above list and done a sample coordination to give you an idea of what one looks like (see the frequency coordination chart, at right). I’m sure it will seem incredible to some, but I’d expect to take the 51 frequencies listed in this coordination into that venue and have zero wireless problems over the course of the event.

In Conclusion

1. Wireless frequency coordination is the way to predict and prevent most of the issues that are fobbed off as “interference” on live events.

2. Why coordinate? It’s been my experience that coordinated RF systems have very few issues and also have a much higher immunity to surprises (like the opening act that didn’t think they had to tell you that their fiddle player was using a cheapo wireless system). Obviously a coordinated system will still be vulnerable to, say, a local news crew coming into the venue with a 100 mW transmitter that’s set right on top of one of your working frequencies, but I find it does make it easier to track down that sort of problem when the rest of the system is working flawlessly.

3. Any coordination is better than no coordination. Even if there’s only an opportunity for coordination for the first date of a tour (or the first day of rehearsals), you’ll at least be free of “self made” interference. This means if issues are encountered on the second date, you’ll know that they’re actual local interference and can move the affected channels.

4. With respect to point 2, I’ve generally found that when I do end up chasing problems with coordinated systems, they’re “real” problems and not “ghosts.” In other words, the problems tend to be actual equipment failures (i.e., broken antennas or a transmitter with an electronic fault, etc.) rather than frequency problems.

Ike Zimbel has worked in pro audio for 35-plus years, and during that time he has served as a wireless technician and coordinator, live engineer, studio technician, audio supervisor for TV broadcasts, and has also managed manufacturing and production companies. He runs Zimbel Audio Productions (zimbelaudio.com) in Toronto, specializing in wireless frequency coordination and equipment repair/modifications.