This To That

Something that had been bugging me is that the drum mics need to be repatched between the live console and the recording snakes every time the room switches functions. This is the sort of wear and tear we don’t think twice about in the live world, but it can really take its toll on studio gear, which isn’t built for such use.

One of my responsibilities is to preserve the gear as much as possible, so we ordered an ART S8 mic splitter and an 8-pack of 3-foot XLR jumpers. This allowed me to patch the drum mics into the splitter, and then take one split to the live console and the other to the recording desk.

The transformer-isolated split is patched to the live desk for two reasons: the direct split to the recording console avoids any coloration added by transformers, and the condenser mics can pull their phantom power from the always-on preamps in the control room rack. If I’d patched them the other way around, the practice console would have to be on for the overhead mics to work, since transformers don’t pass DC phantom power.

I labeled both ends of eight short XLR cables and tied them together into a mini-snake, which patched the direct outs from the splitter into the recording drum snake.

I then made a 20-foot version of the same thing and ran the isolated splitter outs to the live console. A quick test revealed that one of the “shorty” XLR cables had a bad shield connection at one end, which wouldn’t usually cause a problem, but when used with a condenser, the cable won’t pass phantom power. I swapped it out, and everything was working fine.

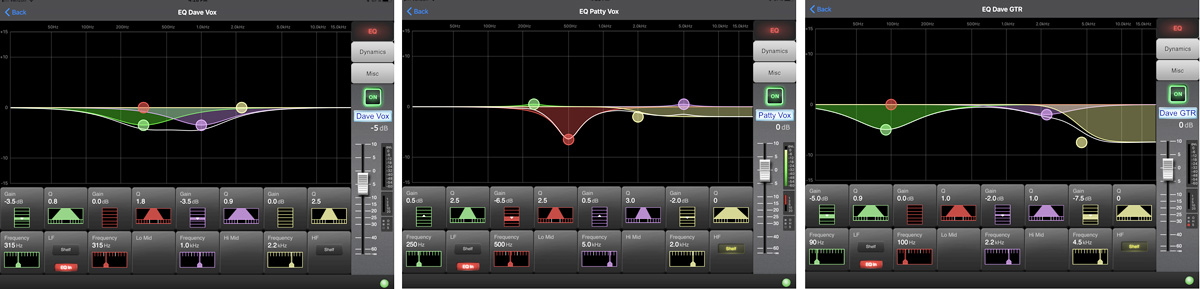

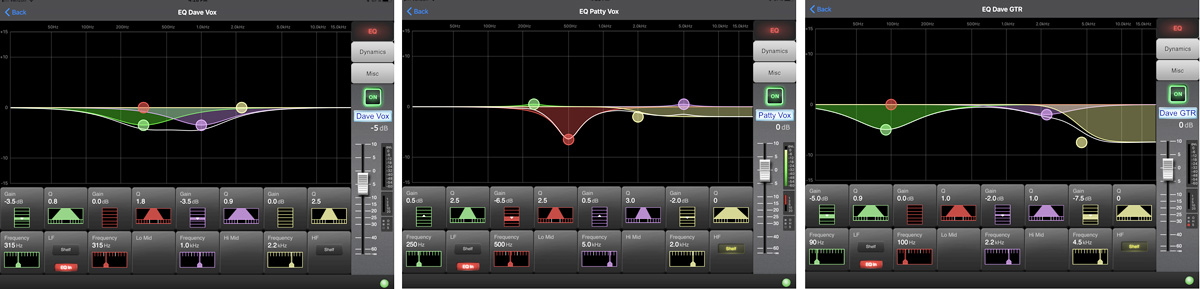

In my opinion, the parametric EQ display on the Soundcraft SI Impact console doesn’t seem to correlate very well with what I hear. The EQ curves displayed in the ViSi Remote app, running on Dave’s iPad, seem to much more closely resemble what the filters are actually doing.

I snapped a few screenshots because I want to reiterate the point made in my previous article: a well-designed, well-tuned system needs very little EQ to sound good. The inputs have one or two filters to tame resonances, but that’s about it.

Steady Improvement

I also feel that it’s important to note that my first suggested solution to an issue is not to throw money at it, but rather to try to solve the problem by working with the current equipment or checking to see if there’s anything else in our inventory that could improve things. Often, repositioning a mic or rerouting a cable is enough. Only if the issue persists will I recommend spending some of the studio budget to solve the problem.

Also, a small amount of money can go a long way: a few rolls of spike tape cost only a couple dollars, for example, but the clear labeling of cables within the system means less hassle, faster setup, and lower overhead costs as a result. Put another way, taking the time to get the little stuff right the first time means that I (and the other engineers) have more time to focus on the projects at hand. I’m less likely to get mixes out on time if I’m spending hours tracing cable runs.

In speaking with Dave about the gradual but steady improvement of capabilities and sound quality, he told me, “In the seventies, I was out in LA with all of the rock bands using analog. And now everything is all digital, and I’m a convert. I’m completely converted. The fidelity of the modern systems is just incredible. We’re digital all the way through. The guitars are analog, the mics are analog, and everything after that is digital.

“Except your ears,” he added, laughing. “Those are analog, hopefully.”

Send Jonah your questions at [email protected].