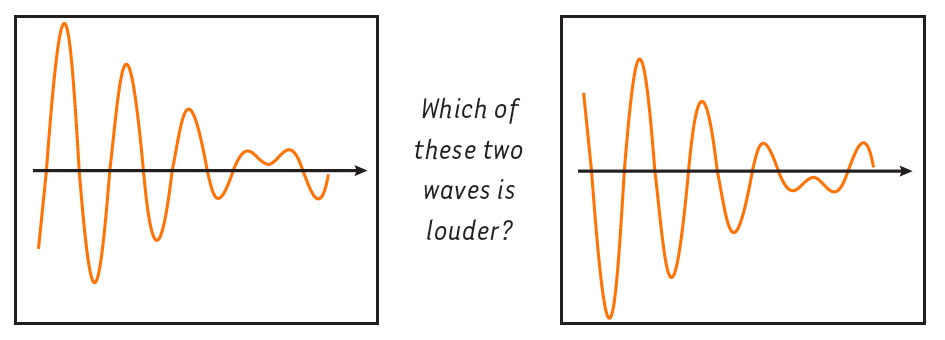

2A. AVERAGE VS. PEAK LEVEL…Which of these two waves is louder?

The answer is: Both have the same loudness. Both have the same average and maximum peak level.

The first wave is identical to the second except its polarity is exactly reversed.

Think of this picture as the graph of the movement of a drumhead seen from the front and back side.

The terms average and peak are a bit misleading if we consider the upgoing direction as positive and the down-going as negative, because the top wave has a maximum in the positive direction and the bottom has a maximum in the negative; however the absolute value of the greatest peak in each wave is the same, so we say each wave has the same maximum peak level.

Over a long period of time, the average of the positive and negative numbers must be zero, which is the static pressure of the atmosphere (the position of the drumhead at rest).

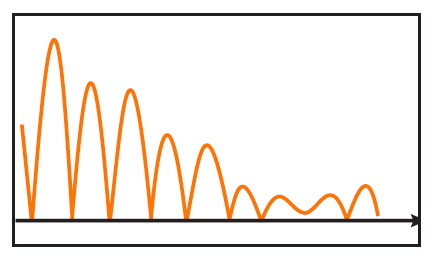

However, the ear generally ignores polarity when it considers loudness, so it sees this wave rectified (pictured), where all the negative segments have been converted to a positive, or more correctly, absolute value.

The average value of this rectified wave over time is somewhere between its peak value and zero; our meters determine this average depending on the method of averaging and the time length of the average.

Sometimes we set our SPL meters to read peak level, but generally we set them to read average sound pressure level because this correlates closer to how the ear hears.

For proper monitor calibration, a good SPL meter should use the RMS averaging method, as opposed to a simple averaging which can produce as much as 2 dB measurement error.

RMS ignores issues such as phase shift and tells us the true energy level of the recording. The word average in this book can refer to the true RMS level or the simple average; when it is important, I will specifically say RMS.

2B. CREST FACTOR, also known as PEAK-TO-RMS RATIO, is the difference between the RMS level of a musical passage and its instantaneous peak level.

In practice, any averaging meter may be used, e.g. if a fortissimo passage measures -20 dBFS on the averaging meter and the highest momentary peak is -3 dBFS on the peak meter, it has a crest factor of 17 dB.

It is extremely rare to encounter a piece of music with a crest factor greater than 20 dB, so this is the commonly cited maximum.

When the dynamic range (the difference between the loudest and softest passages) of a recording has been reduced, we say the material has been compressed, and that a compressed recording has a lower crest factor than an uncompressed one.

And the # 1 most confusing audio term is…

1. VOLUME… is usually associated with an audio level control, but is an imprecise consumer term. Volume is measured in quarts, liters and cubic meters! The words more properly used in our art are Level and Loudness.

The big problem is that consumers use the term ambiguously, to mean both the loudness they perceive and the position of the “volume control”—a perfect example of confusing gain with level!

So in this book I prefer to use the professional term monitor control. I rarely use the word volume except when speaking informally to clients or consumers, and occasionally succumb to saying “volume control” when referring to a consumer’s system.

Editor Note: This article is the first part in a series on decibels, excerpted from Bob Katz’s book Mastering Audio: The Art and The Science.

To acquire this book, click over to the Focal Press.