Today’s Standard

It’s reasonable to estimate that a large concert rig, on the road 52 weeks a year, could save a couple of thousand dollars in annual fuel costs by employing neo magnets as opposed to heavier ceramic magnets.

But perhaps more importantly, large arrays of lightweight loudspeakers can be flown with fewer chain motors and smaller support structures.

Aging/outdated infrastructure in sports arenas and theatres is routinely being down-rated in load capacity, so the lighter the rig, the better.

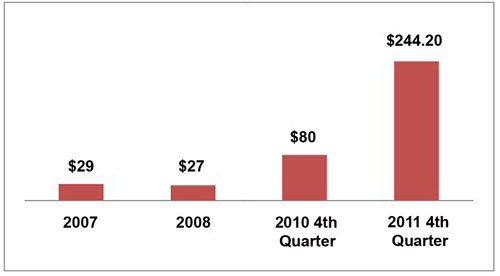

The problem is that a whole lot of concerns want neo for their products and there’s currently not enough to go around, forcing a dramatic price increase over the past few years. Prices have been decreasing somewhat this year, but it’s difficult to predict if the downward trend will continue, stabilize, or reverse.

In addition to the many applications noted earlier in this article, neo is also used in wind generators because the low weight permits larger units to be placed on smaller support structures. This application, perhaps more than any other, has the neo industry in a jam because China, which produces about 97 percent of the world’s supply, stated it would stop exporting neo in order to use the entire supply domestically, mainly for wind generator farms.

This plan will require about 59,000 tons of material in the coming year to make high-strength magnets – more than the nation’s annual output. Fortunately, the government later softened it’s position, but the price has nonetheless skyrocketed.

While researching this article, I discovered that neo isn’t particularly rare at all; it’s only geo-politically limited. There’s plenty of it in the earth. In terms of overall quantity, the amount is approximately equal to cobalt.

But like cobalt, neo is not found everywhere, only in certain locations – though it is more widely distributed in the earth, geographically speaking. Relatively few mining companies want to engage in neo extraction and refinement because the process is difficult and expensive, as well as causing byproducts of toxic pollutants that must be managed.

Molycorp owns a mine in the U.S. that is the only rare earth oxide producer in the western hemisphere, and the largest outside of China. The company has been seeking to ramp up neo production.

In September 2011, Molycorp CEO Mark A. Smith testified before a U.S. House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee, stating, “China is clearly warning that they will consume more of their own rare earths and export less, and that they see tight supplies of rare earths as representing an ‘irreversible’ trend. The U.S. must roll up its sleeves and get to building its own domestic rare earth manufacturing supply chain. We must move as rapidly as possible to a position where our economy and our national security interests are no longer tied to declining Chinese rare earth exports.”