Ratio: This term is a little easier to understand regarding compression.

In an ordinary signal-chain stage, such as a mixing board’s channel fader, the gain is linear:

Any increase in level at the circuit’s input will be matched by an identical level increase at the output.

If it’s a unity-gain stage (meaning that no amplification is occurring), three more decibels going into the circuit will result in 3 dB coming out. This is a 1:1 ratio: what you put in is the same as what the circuit pumps out.

A compressor changes this ratio, but only in the region of the dynamic range that’s above the compression threshold.

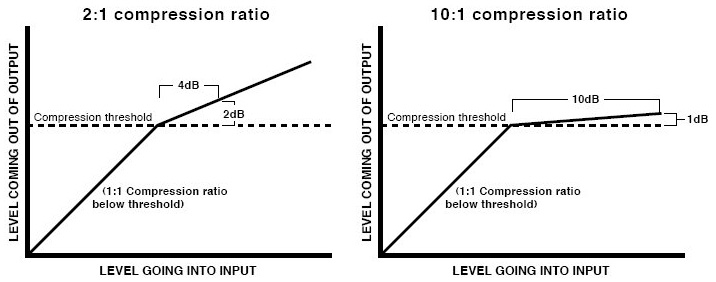

If the compressor is set for a 2:1 ratio, that means that when the signal level is above the threshold, increasing the level going into the circuit by 2 dB will result in only 1 dB more amplitude at the output.

Likewise, pumping in an extra 10 dB will result in only 5 dB of output. But if the signal is below the compression threshold, pumping in an extra 10 dB will result in a 10 dB increase at the output—the compressor is unity-gain (1:1 ratio) below the threshold.

Figure 2 shows how this works in graph form. It should be easy to see that if you set the compression ratio higher, you need to pump even more signal into the circuit to get the same rise in output: with a 10:1 ratio, a whopping 20 dB of extra signal level will cause the compressor’s output to rise by only 2 dB.

With an infinite compression ratio, you can’t get the output to rise over the threshold no matter how much signal you put into the circuit. Any compression stronger than about 20:1 is considered limiting.

A limiter is like the flipside of a noise gate—it’s kind of black-or-white, either doing its thing or doing nothing (depending on the signal level at the moment), without much gray area in between.

Combining things, Figure 3 is a graph showing how having both an expander and a soft-knee compressor in your chain affects a signal’s dynamics.

Attack & Decay: These parameters are essentially the same as in an expander.

Attack specifies how fast the compressor gets to work when presented with a signal that’s above its threshold, and decay specifies how fast it returns to a 1:1 ratio when the signal falls below the threshold.

With a soft-knee compressor and a signal that slowly rises and falls in level, attack and decay may not come into play at all—but when presented with things like sudden transients, they can have a definite effect on a sound.

As I mentioned, in a combined compressor/expander unit there may be just one set of attack and decay knobs; I tend to leave mine set to a very fast attack and a medium-length decay, which seems to work just fine for most sounds.