It’s 9 am and I’ve just tumbled off the bus into today’s venue, a.k.a., “The Naming Rights Arena,” another stop on the five-month, 59-city Rock This Country tour by Shania Twain that I’m working with VER Tour Sound.

The first hour is spent helping the rest of the audio crew as we tip the first of two trailers (mostly PA). About an hour later, the second trailer is empty as well, and I’m able get to focus on my “real” job as RF technician for the tour, which usually runs 56 channels of wireless systems on each show. (At one stop we had 89 channels running.)

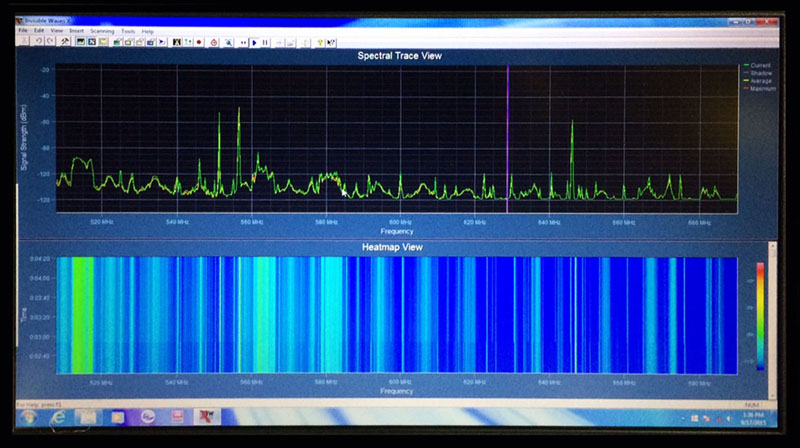

First thing, I set up my scanner, an Invisible Waves IWx RF Command Center. I generally begin by taking a 200 MHz wide scan from 500 MHz to 700 MHz, as I’ve been finding that the bandwidth below 500 MHz is usually out of bounds in the U.S. This is due to those frequencies being re-allocated to public safety in many cities.

The first pass is often an early indication of what kind of day I’m going to have – if there are relatively few DTV channels and a low noise floor, things are going to be pretty straightforward (Figure 1). If not (Figure 2), read on…

Once the scan has run for at least five minutes (it lays down more detail on successive passes), I save it as a .csv file that is then imported into Intermodulation Analysis System (IAS), the frequency coordination program from Professional Wireless Systems that I’ve used since 2008.

Whenever possible (i.e., when there’s an Internet connection available), I also upload my scan to the IAS database so that other users can access it.

About 90 percent of the time, the scan will have nothing but the local DTV channels that are present in the arena, but occasionally there will be a few other carriers present as well, typically the house intercom base station frequencies.

For the most part I’ve decided to work around these, for three reasons: They’re often already in a DTV channel that I’m already staying out of (not sure if this is deliberate); the house audio folks are often not in until 1 pm to turn them off; and even if they can be turned off, they can be turned on again, as in the common scenario where a different house audio tech comes in for the show and says, “Hey, those are usually turned on…”

At this point I usually wander down to catering for breakfast and work on my coordination with the newly acquired scan data. This coordination is already “roughed in” the night before, but I’ve found that a scan on show day is really needed to finish it, usually because I uncover at least one more DTV channel than was listed in the database.

Coordination done, it’s time to head back down to the arena floor (at this point the stage has been built but is still out in the middle of the floor). I temporarily park my RF rack next to the stage left PA distro, power it up and program any frequency changes into the eight Sennheiser EM3732-II receivers and seven SKM2000 IEM transmitters.

I then sync or manually program the corresponding mics and beltpacks. (We’re using the 2000 Series beltpacks into the 3732 receivers for band vocals, and that combination won’t sync). If there are changes needed in the Telex BTR intercom system, I also power up that rack and make those changes.

Once everything has been programmed, including redundant spares, the racks are unplugged and rolled into position opposite where they’ll go when the stage is moved into place.

By this point, the stage has been pre-wired, and everything else that can be done is done. Time for lunch.