Because so many audio systems these days use digital audio in some form or another, it’s becoming more necessary to understand what happens to our audio in the process, and how. Latency is a somewhat necessary evil. We like things processed, and that comes at a price. For many applications, latency isn’t an issue or noticeable. But in other applications, every millisecond counts.

“Why does latency matter to me then?” you may be asking yourself. Well, latency is everywhere in the digital world and it’s important that audio techs of all levels understand the pieces that make up our systems.

The Metrics

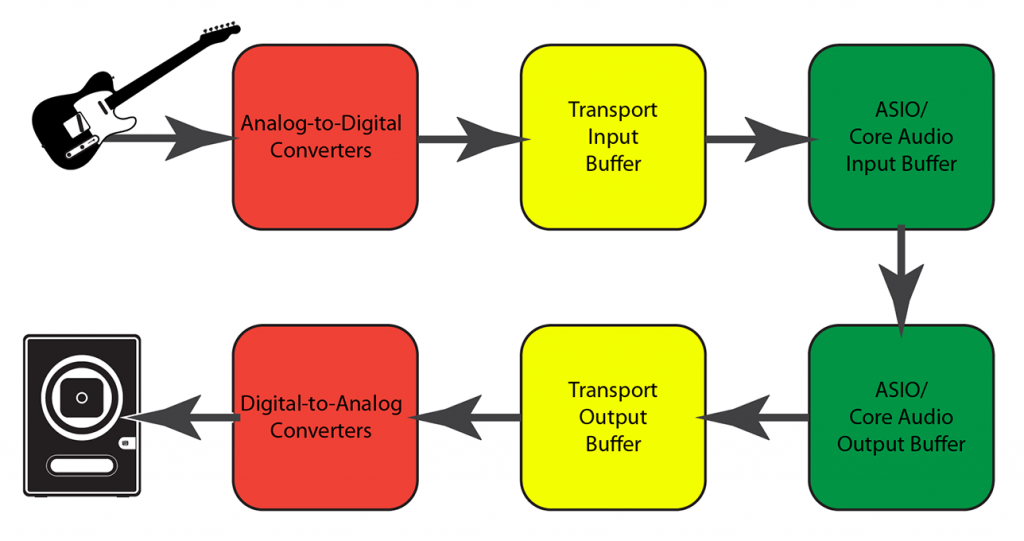

Plainly, latency is a delay caused by the time it takes to process a digital signal – an unavoidable part of any digital system. The very moment we step into the digital realm, latency becomes part of the deal. Electrical signal must be converted into digital information for digital processors and computers to understand and manipulate, then converted back into an electrical signal on the way out.

Any changes to digital signals – even changes as basic as a level change or EQ – are simply mathematical operations carried out by the mixer’s processors. And the math takes time.

In digital systems, latency is measured in milliseconds (ms), 1/1000th of a second. Delay plays an important role in how our brains “localize” sound sources – how we determine which direction sounds are coming from. For sounds that are percussive – like a vibraphone – or have a lot of high-frequency content – like a cymbal hit – even a few milliseconds of delay can be enough to alter the localization process.

There are many variables in play, but every reputable manufacturer should have latency specs listed in manuals and data sheets. If you work with a digital console, use your favorite search engine to look up its latency, just for giggles.

In my research, I looked up the latency time of 10 common consoles ranging from prosumer to touring grade and 2 ms or less was a definite theme. Other pieces of gear have what some call “ultra-low latency” with less than 1 ms of latency.

One other note: latency is not frequency dependent – it affects all frequencies equally.

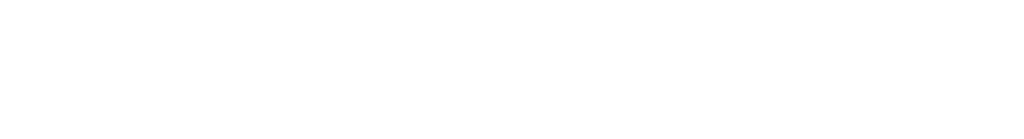

FOH Vs Monitors

Sound takes time to travel in the air, about 1 ms per foot. It takes quite a bit of time for sound to reach listeners’ ears at front of house. Because of this, latency isn’t as detrimental in the front-of-house signal chain, and some engineers add a lot of fun toys that bring “something special” to their sound. Compared to the “flight time” from the PA to the listeners, a few more ms here or there from lots of plugins isn’t necessarily a game changer.

However, monitor wedges — and especially in-ear monitors [IEMs] — are placed close to the listener (right inside the ear canal, in the case of IEMs). Suddenly latency matters significantly. If musicians are playing an instrument and perceive a delay between their strumming/singing/banging and what they’re hearing, it can cause an uncomfortable or confusing sensation.

When IEMs are worn by singers and horn players, even slight latency can cause unpleasant tonal changes because the signal can interact with the natural vibrations of the musician’s skull as they perform. This causes a disconnect between the musicians and the music – which we never want. Great care should be taken when, additionally, making the IEMs wireless.

What To Remember

Computers can often add a lot of latency. Running any audio out of a console and into a separate computer, then back to the board again (like an outboard effects rack) can add tremendous latency. This can result in the various mix elements arriving at the main mix bus at different times. If one set of channels is being greatly delayed by a plugin, it will no longer be in time with the set of channels that are not going through the plugin. Some plugin hosts use latency compensation to ensure that the un-processed channels are delayed sufficiently to keep everything in sync – but be aware of how much latency might be incurred.

Wireless networks (WiFi) have some basic limitations that make them unsuitable for audio signal transmission. Don’t panic – that’s why most WiFi-enabled systems use the WiFi simply to transfer control data, not the actual audio signals. Since WiFi is so highly undependable, I can’t in good faith recommend using WiFi audio in any situation you’re not willing to lose it all. It’s not a matter of “if” it will fail, it’s when.

Something Useful

Let’s focus on implementing this new knowledge. For instance, let’s say you’ve got two mics on the snare. If you insert a plugin on one channel (perhaps a compressor) you’re adding latency to that channel. If you were to then combine both snare channels together in the mix, you’re combining a delayed channel with an un-delayed channel, and this can cause an unpleasant interaction called a comb filter. Because you’ve shifted one of the channels over (even by a very tiny amount) in time, the relationship between these two inputs has shifted. It might sound awesome or it might be terrible – just be aware!

If you’ve experimented with using a separate computer as an FX rack, use software built to be an FX rack not a digital audio workstation (DAW), which do a lot more than just process live audio and thus can tack on a lot of latency.

A very effective way to reduce system latency is to pick a sample rate and stick with it. If devices need to perform sample rate conversion (SRC) on incoming digital signal, this adds latency that could be avoided by setting all the devices to the same clock rate. This is less about which sample rate to choose and more about just selecting one and being consistent about it. (I’m a personal fan of 48 kHz sample rate – bring on the hate mail…)

Further, use the console’s onboard processing whenever possible. It’s best if you have a very specific need for anything outboard and then use it as little as possible. Once you can nail down working with stock plugins, then it may be time to graduate to outboard. Maybe.

Latency is one of the many building blocks of digital audio, another piece to add to your bookshelf of knowledge. These types of topics can get complicated but taking it one step at a time will lead to a better understanding of audio engineering.