Sixty years. It’s amazing what has changed over that period of time. Gas was 30 cents a gallon, a postage stamp cost 4 cents, the transistor radio was newly invented, JBL had recently entered the pro audio market in association with Fender guitar amps, and the Shure SM58 was still almost a decade away from its introduction.

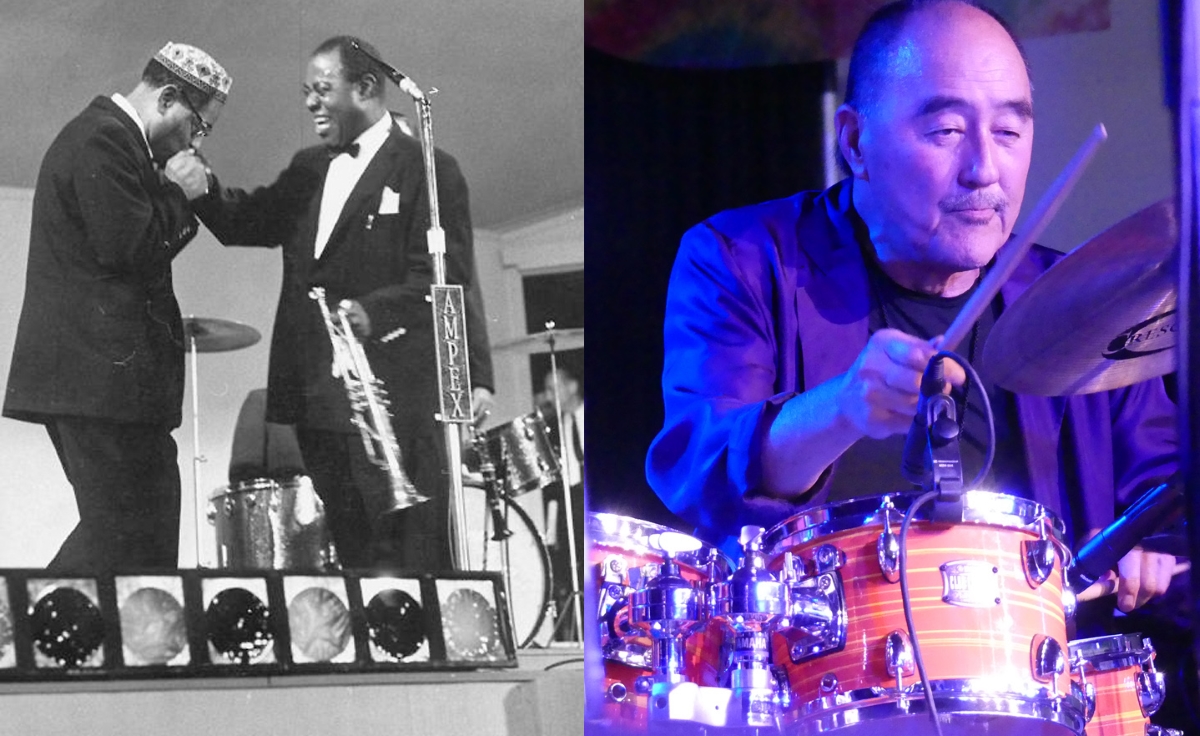

And in 1958, the first Monterey Jazz Festival was held, with headliners such as Billie Holiday, Dizzie Gillespie, Dave Brubeck, and Louis Armstrong.

While covering the 60th festival last September, I was given a copy of the December 1958 issue of Audio magazine that featured an article written by audio pioneer R.J. Tinkham detailing the preparations and audio system for that first festival.

Among his many accomplishments, Tinkham founded the professional tape recorder manufacturer Magnecord, worked at Shure and Ampex, and co-founded Vega to manufacture some of the first wireless microphone systems used in radio and television. Using his detailed article as a source, we’ll look at the ways sound reinforcement has changed in Monterey over the decades.

The Beginnings

With radio DJ Jimmy Lyons in the lead, a group of Monterey music enthusiasts proposed to host a jazz festival, and in conjunction with the city council, selected the county fairgrounds for the event. Specifically, the horse-show arena would serve as the concert site where a stage and seating would be erected.

Two members of the committee tasked with realizing the festival were musicians and audio aficionados who were adamant that the audience would be expecting quality sound reinforcement throughout the listening area.

As a result, in July 1958, Ampex Corporation was asked to assist with the acoustic design and sound reinforcement – just a few months before the October event – a process headed by Tinkham, research director Walter Selsted and audio engineer Harold Lindsay.

Their initial actions included persuading the committee to move the planned site of the stage to another spot in the arena where the sound would shoot away from – rather than toward – a group of buildings that would generate slapback echo (tested with hand claps). Instead, the sonic energy would be attenuated by a grove of trees outside the far end of the arena. In addition, the grounds were originally contoured in a slightly raised mound, so the high center was bulldozed to create a flat, mildly sloped surface to seat the anticipated 6,000 listeners.

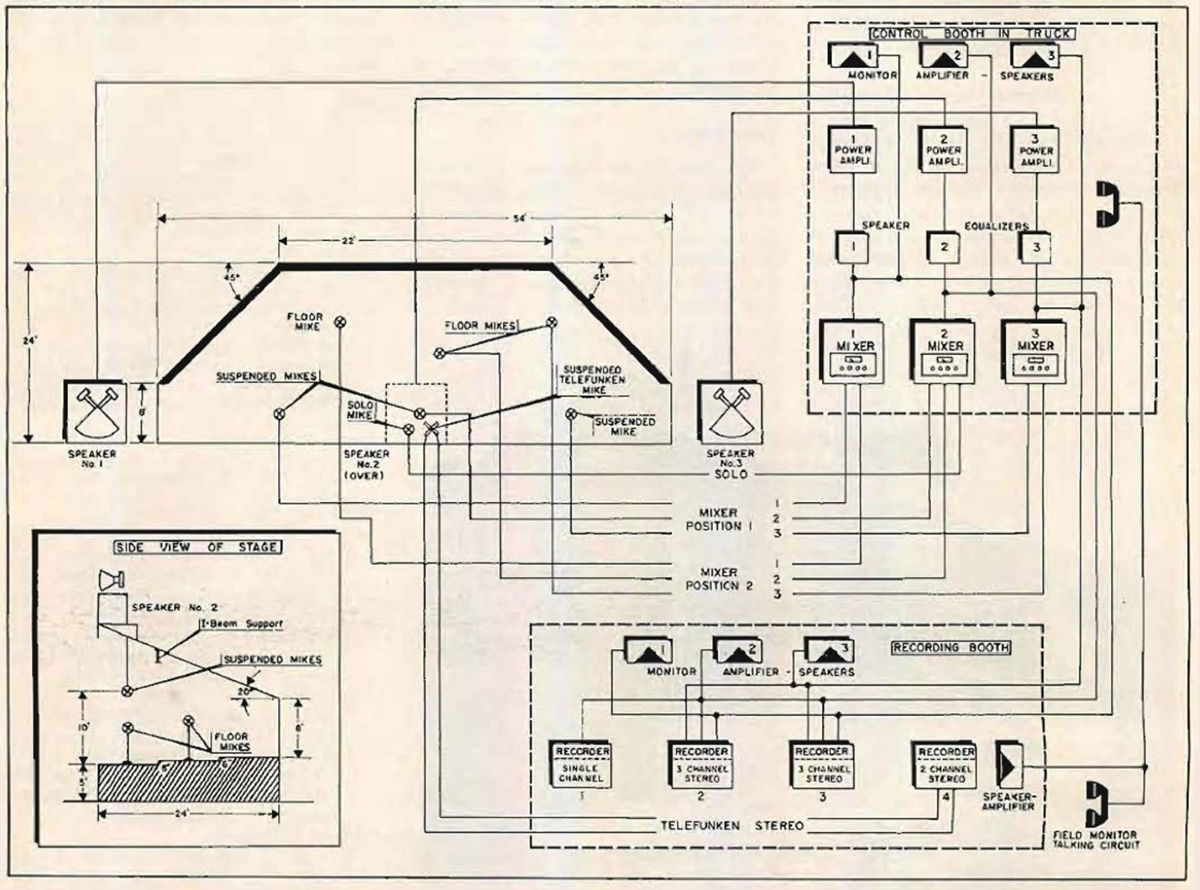

The stage needed to accommodate acts ranging from small combos to a 75-piece orchestra and had a proposed budget of $1,500. With advance ticket sales bringing in sufficient revenue, the final design for the stage was upgraded from a flat platform with hard back and side walls (angled outward at 45 degrees) to a more functional form that included stepped risers for the orchestra sections, a sloped ceiling to project sound forward, and a width of 54 feet at the front. The stage faced an audience seating area approximately 300 feet deep by 150 feet wide, and “was designed to reinforce the direct sound for the box holders in the front third of the audience space.”

Projecting The Sound

Now the tale becomes even more interesting. To reinforce everything from combos to orchestras, a total of just six microphones – three flown and three on stage – captured the music. With such a variety of acts, this complement of mics had to adequately serve vocalists and announcers, instrumental soloists, combos and rhythm sections, and orchestral ensembles.

The mics worked with a left/center/right sound reinforcement system, with a separate mixer for each channel feeding amplifiers and loudspeaker stacks – three sets of LF enclosures plus multicellular horns, crossed over at a fairly low frequency.

As with a group of acoustic musicians and/or vocalists clustered around a single mic, the ensembles needed to pay careful attention to blending their sounds acoustically, and soloists had to move closer when it was their turn. Contrast this method to most contemporary mixing, where the drum kit usually has multiple mics, each singer and instrumentalist has a mic, and instruments like electric bass may have a DI and a mic on the onstage amplifier, with tonal and level blending via a multichannel mixing console.

Front of house engineer Nick Malgieri, who has run sound at the festival’s Arena Stage for several years, notes that he currently utilizes about 40 channels for some of the acts. The piano itself is handled with five mics (though not all are used simultaneously) positioned at various locations close to and above the soundboard. The goal is to fully capture the acoustic sound of the instrument while preventing bleed from nearby percussion and other instruments.