Let the countdown begin…

10. Musicians feel most comfortable and play best when they hear what they need to hear on the stage.

Of course, experienced monitor and recording engineers already know this, but it’s something for those less experienced to think about. No, it’s not about how much power you have or what kind of monitor wedges. It’s about psychology.

And I think it’s true that if you become good at monitors and understand how to please musicians, you’re 90 percent there towards becoming a good mix engineer. Sure, the last 10 percent might be the “magic” but you can’t make magic without the basics.

9. Sound travels at 1,130 feet per second, at sea level, at 68 degrees F and 4 percent relative humidity.

This is important because if you understand how sound propagates, you’ll automatically know more about microphone placement, setting delay towers, and things like delaying the mains to the backline. And you should also know that the speed changes with temperature, humidity, and altitude. (If you don’t, it’s a good idea to look it up.)

8. The Inverse Square Law.

You know, the thing about a doubling of the distance from the source means that the acoustic power is cut by 1/4, right? This applies all over the place, from mic technique to loudspeaker arrays. It relates to how much power will be needed from the power amplifiers.

For instance, if you normally cover an audience at 20 to 60 feet from your stacks, but for the next gig, the audience will be 40 to 100 feet away, how much more power will you need to maintain about the same acoustic power? About four times as much! Maybe think about delay stacks (see number 9).

7. The equal loudness contours of the human hearing system.

Back in the 1930s, Harvey Fletcher and the team at Bell Labs did some tests resulting in this graph. What it means is that the human ear is most sensitive in the upper mid-range frequencies, and least sensitive at very low and very high frequencies. In other words, to hear a tone at 100 Hz equally as “loud” as one at 3.5 kHz, it must be 15 dB louder! (This is assuming the 3.5 kHz tone was at 85 dB SPL).

The implications are that to provide a really good, full mix, you need a combination of lots of power, a carefully designed subwoofer system, and a brain capable of realizing that it’s easy to overpower peoples’ ears in the mid range. Not to mention that distortion, especially in the mids, is really obnoxious. Which brings me to…

6. Distortion really sucks, unless part of the “sound.”

I’m often amazed how seemingly intelligent people who otherwise know what they’re doing don’t seem to notice fairly high levels of unintentional distortion.

The first step in eliminating it is to learn about the causes, from gain structure to faulty connections to cold solder joints to aging tubes. Second, and perhaps even more important, is to learn how to hear and identify distortion. Is it harmonic distortion? Gross overload of one of the channels? Intermittent?

And then third, please do something about it!

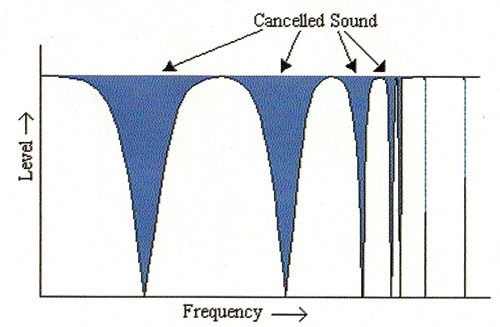

5. Sound from the same source can combine acoustically out of phase to give a “bump” of +3 dB (doubling of power) all the way to complete cancellation, or minus infinity.

For instance, the nodes (bumps) and modes (cancellations) of bass signals—due to standing waves in the room—can actually completely cancel in some places. Zip, zero, nada. And let’s think what happens if you place your RTA mic in that spot and take a reading. There will be a big notch in the lows at a particular frequency.

This is one reason why it’s important to take a multitude of measurements before getting a real understanding of the bass in a particular room.

4. What wasn’t captured upstream at the mics or pickups can’t be recreated downstream.

Sure, plugins, effects, DSP and all that stuff can be cool and is often needed to create the sound you want, but the idea that an SM57 can be made into a U47 via “mic modeling” is absurd.

Distorted sounds can’t be fixed (see #6). Or as computer geeks stated in the 1950s: “garbage in, garbage out.” This is not to imply that an SM57 is garbage. To the contrary — it’s a great mic that has a ton of uses. But there are certain things it does not capture and no amount of processing can change that after the fact.

An audio chain is only as strong as the weakest link upstream.

3. The sound of the performance should match the music of the performance, simple as that.

Big band music should not sound like rock. Rock should not sound like classical. Classical should not sound like there’s a sound system present.

Most often, it’s a good idea to go to the original source to understand how a mix should sound. If the “original” is a record, then it’s a good idea to figure out what effects were used on that record, how it was EQ’d, and the overall “vibe.” If the original is a live performance of acoustic instruments and voices, then check it out and learn how it’s “supposed to sound.”

2. Grounding.

Let’s not mince words here: this is a subject that must be understood. If there’s more than one path to ground in an audio system, and the resistance to ground is different between them, there will be problems with hum and buzz.

Related to this is how you terminate connections, especially if any parts of the system go back and forth from balanced to unbalanced terminations.

It’s also a good idea to learn the sonic signatures of different kinds of hum and buzz to therefore speed up your troubleshooting when the time comes. This is because some types of buzz are not related to grounding problems, but instead may be power supply issues, for instance.

1. Gain structure.

This is the main one, the real deal. The thing that — if you can’t learn, or don’t understand or have forgotten — will get you into more trouble than anything else. There will be more noise and/or more distortion in the system unless you get this right. And there will be less gain before feedback, too.

So here’s the deal: every input and every device has an optimum range of levels it wants to see or wants to work with. If you’re feeding something a signal that is too low, you have to make this up somewhere, and therefore you’ll be bringing up the noise more than it should be. And that noise will be in your signal from then on.

Oh, sure, there are noise reduction devices you can use, but why do that when proper gain structure will take care of it for you? And really, we should use the least processing possible to get the job done because things sound better that way.

Alternatively, if an input or a mix bus is fed too much signal, headroom will run out, which means adding distortion is being added. And this, also, cannot be removed later. Artistically adding distortion via plugins, hot-rodded guitar amps or certain outboard gear can be cool. Adding it by slamming inputs or the mix bus is not cool.

For instance, if a wireless microphone output can be set at line level, but you set it to mic level and connect it to a mic input on your mixer, there will be more noise than if the line output is connected to the line input. Why? Because essentially you’re padding down the output then boosting it back up again with a high-gain mic preamp.

Sure, sometimes you might want to put the signal through a transformer or other “good” distortion device — just be aware that from a gain structure point of view, this is not ideal.

OK, that’s the list. If you’ve already mastered these things, great! You’re probably doing better mixes, with more gain before feedback, better coverage and happier musicians than those who don’t. But please don’t rest on your laurels — get out there and learn as much as you can.

Those of us going to your shows will know it when we hear it!