I was watching something on TV recently, and after hearing multiple “plosives” (P’s and B’s and T’s) just booming away through my speakers, I quipped, “Can we please get a high pass on that mic!”

Then I realized there still may be a number of less-experienced sound techs out there who are not yet acquainted with the high-pass filter (HPF). Allow me to make the introduction.

The HPF, whose control typically lingers near the top of the channel strip, does just what it sounds like — it lets high frequencies pass while blocking lows. And by high frequencies, we mean any frequency higher than the threshold set by the control.

I suspect that’s part of the problem with the HPF; some might think that it will cut out all the low end and make the sound tinny and thin. You certainly can achieve that effect, but it’s not the intended result.

Slippery Slopes

The HPF comes in two flavors—a fixed frequency filter activated by a switch (commonly found on lower-end analog boards) and a variable threshold filter with an on-off switch (found on everything else). The former type typically has a hinge point of somewhere between 75 and 100 Hz, and has a slope of anywhere between 6 and 24 dB per octave.

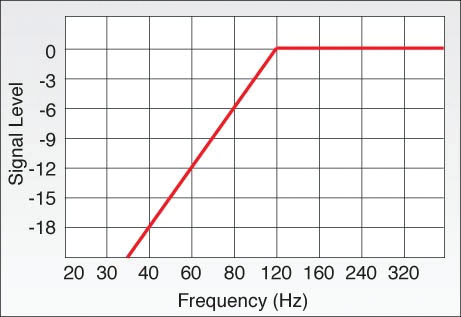

Understanding slope is helpful in knowing how to employ HPF’s, though you can’t do much about it with a fixed frequency version. Let’s take a 12 dB per octave slope; that means that starting at the corner frequency, for every halving of the frequency (an octave), the output drops by 12 dB.

So, if you have a HPF with a corner of 120 Hz, by the time you get to 60 Hz (one octave) the signal is lowered by 12 dB. At 30 Hz (another octave) it’s down a total of 24 dB. Perhaps an illustration will help.

Figure 1 offers, as you can see, a fairly gentle slope. An 18 dB per octave slope would be steeper, a 24 dB slope steeper still. It’s helpful to know the slope of the filter, though many manufacturers don’t publish it. You can get a good idea of how steep it is by sweeping the control up and seeing how quickly the low end falls off (assuming you have a threshold control).

Putting It To Work

In practical use, I approach HPFs this way – if I’m dealing with a simple switch (that is, no control) I turn them on for every channel on the console except for the kick, floor tom, bass and electronic keyboard channels. Generally speaking, there’s not much musical content below 75 to 100 Hz for vocals, acoustic guitar or much anything else, and what is there typically muddies up the sound. Engaging the HPF in this way helps eliminate a lot of low-end rumble as well as low frequency feedback in the monitors.

If there’s a control, I turn it on for every channel and adjust the individual controls as needed. For a kick, I might have the HPF set to 30 to 50 Hz, just to clean up the extreme low end. On vocals, I normally start at 120 Hz, but sometimes run up as high as 150 to 180 Hz depending on the voice, the microphone, and what I’m hearing.

If plosives are a problem, turning the HPF up can take some of them out. It can also make the person speaking sound very thin and tinny, so be careful. For other instruments like acoustic guitar, I like an HPF at 150 Hz or so to tame some of the body resonances. Again, you have to be careful, but this is a good place to start. (Always listen…)

You can also employ HPF on things like cymbals. I have my HPF on the hi-hat channel turned way up around 500 Hz or so. This cuts out some of the bleed from the toms and snare, cleaning up the hi-hat sound. If you want the overheads to act as cymbal mics, do the same thing. On the other hand, if you want to pick up the toms and snare, but not the kick, try setting it around 120 Hz or so.

As with every other control on a console, it’s vital to listen, not just follow numbers. The best way to learn what the HPF sounds like on your specific console is put on some headphones, solo up the channel and either turn it on or off, or turn it on and sweep the threshold up and down. When you arrive at something that sounds pleasing, stop.