Formalizing The Blues

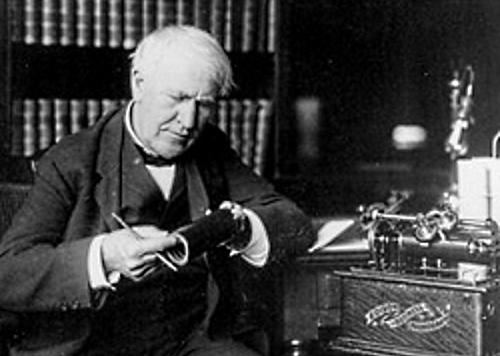

The exclusive patent rights that Edison, Columbia and Victor had, ended in 1917, but they continued to dominate the record industry though others were finding opportunities at the fringes. The growth of independent production accelerated with the introduction of the vacuum tube to the process which made recording easier and more portable.

By the beginning of the 1920s, regional, ethnic and culturally different music was beginning to be recorded by traveling field recordists who carried their equipment in the backs of their cars. They would set up in hotel rooms, bars, and music halls and record the best local performers.

The artist was paid a small fee and the recordist/producer would press records and attempt to sell the recording to the big city record companies. Initially, these recordings had little impact on the music industry but would have a significant influence on future generations of musical artists. Music that had never before been written down, documented or copyrighted was now being codified for future generations. Did the recording of ethnic and regional blues, hillbilly, or folk music change this music? Of course it did.

The recording process forced a honing of these songs into a structure that was just long enough to fill a 10-inch, 78 rpm record. This restriction became a catalyst in formalizing the structure of the ethnic song. It also immortalized forever those emotions that previously were conveyed only in the presence of the blues, hillbilly, or folk singers’ performance. These recordings captured the music of the people, in particular black music, as well as hillbilly (later called country and western) and folk.

Music that only existed as oral histories was now quantifiable and directly comparable outside of a public performance. This music now had stable roots from which others would build. Once created, the records provided a means of musical recollection of the life and times of these popular performers.

Recordings also changed the standards of ethnic composition and performances. When this music was entirely by oral delivery, cliché and borrowed music wasn’t a problem for the performers since those who were listening would seldom have heard the original source, and if they had, it was unlikely they would have been able to make comparisons from memory.

The commodification of the performance allowed aficionados of the music to quickly compare and know when they heard someone play a stolen classic.

Building On The Roots

Throughout the 20th century, the records of blues, hillbilly and folk artists of earlier times have been available for all to hear, providing a starting point for later performers to build on in their times. While this ethnic and regional music continued to evolve as an oral tradition, it was no longer necessary to follow these singers from one gin joint, music hall, or saloon to another in order to hear what they had to say.

Once the records existed, the music could be discovered by each new wave of performers. Through the lyrics and performances of these songs, the recordings captured an impression of the lives, times and places of these singer/songwriters.

Bessie Smith learned to sing the blues by going on the road with Ma Rainey, but Billie Holiday could listen to Bessie’s records, and Aretha could build her music on what she heard in the records of Billie and Bessie.

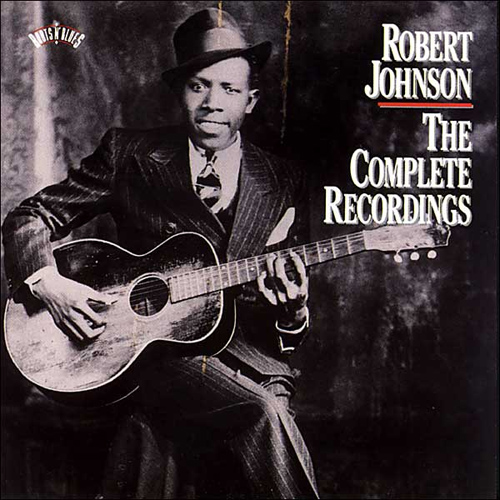

Not only have late 20th century singers been able to look through the phonographic window to the past, so too have instrumentalists. Eric Clapton (and so many others) could sit with Robert Johnson and pick up classic licks, even though Clapton was born seven years after Johnson died.

Few pop music artists are void of influences from artists of the past. Records have connected all the times since the turn of the 20th century into a continuum, but with all the times of the past available at the same time just by playing a record.

As Simon Frith wrote some years ago, “Popular music came to describe a fixed performance, a recording with the right qualities of intimacy or personality, emotional intensity or ease. ‘Broad’ styles of singing taken from vaudeville or the music hall began to sound crude and quaint; …

This change also coincided with a different type of music entrepreneur, the record producer, who, unlike the music hall operator, had little contact with the audience or any experience with trying to please the public on the spot. For the record industry, the audience was essentially anonymous…”

In Europe… In The Beginning… Opera

In Europe right after the turn of the century, armed with a portable recording system, Gramophone’s talent scouting technician Fred Gaisberg traveled all over Europe and into Asia looking for and recording every form of folk music and pub entertainer.

In the beginning “serious” opera stars were loath to involve themselves with such gadgetry, but just when phonograph records were in peril of becoming an exponent of all things rustic, exotic and vulgar, legendary Italian tenor Enrico Caruso was signed in 1902 by the Victor Company and recorded by Gaisberg.

Actually, Caruso was signed to the Gramophone and Typewriter Company Of Italy. He would later sign directly with Victor, where he would have more than 40 top-10 hits. This marked a turning point for the fledgling HMV/Victor record label that now had the opportunity to market high culture into the home.

It made ownership of a gramophone not only acceptable but essential by the best families. The record labels promoted operatic arias that were short enough to fit on a record and they soon became accepted as examples of popular music.

Caruso was a famous opera singer long before making a record, but the recordings he made between 1913 until his death in 1921 made him an international figure and extremely wealthy. His voice became known to millions of people who had never been to an opera and almost everyone with a gramophone had a Caruso record. He was the first artist to have a successful recording career, and the Gramophone and Victor owed their success and survival through their infancy to Caruso’s popularity.

Further development of the recording process and the medium of distribution, the record, became a matter of perfecting the original invention. The amplifier was invented and introduced to the process and new materials and techniques were introduced, but there was little change to the original concept until magnetic recording came along in the 1950s, and CD supplanted records in the 1980s (though in the 21st century some still prefer vinyl).

The Record Player

The expiration of the Edison-Columbia-Victor gramophone and phonograph patents in 1917 meant that dozens of companies entered the market. Record players were built for every taste. Some had features that today make one wonder what the designers were thinking.

The Ko-Hi-Ola for instance, was a phonograph with a built-in grandfather clock, a storage area for records and a “special” secret compartment. As the ad for the unit described, “The Ko-Hi-Ola is more useful than the ordinary phonograph, more ornamental than the usual grandfather’s clock and has exclusive features not found in other machines”.

There were many manufacturers of phonographs. Most machines had some unique sales feature that had little to do with the sound. Most were commercial failures as were the companies that made them. Phonograph players remained mechanical devices for sometime after electric recording began in the early 1920s, but in order to hear the extended response of the electric recordings, larger horns were needed.

The need for better reproduction equipment to hear the improved record quality pushed the development of electric record players, so that by the mid 1930s, the large playback horns were disappearing and replaced with speakers. This was made possible by the development not only of amplification but a low-cost stylus and cartridge that generated an electrical signal that could be amplified. The stylus was now connected to a piezoelectric crystal that when twisted back and forth along the modulating grove would generate an easily amplified alternating current.

Beginning in the 1920s, the gramophone became a centerpiece for an evening’s entertainment with friends. It was a more social instrument compared to the radio that was also becoming a part of the modern home. No one knew for sure what would be on the radio, while on the other hand, the person running the gramophone party had control of the material played. There could be discussion about what was heard and how it differed from other recordings.

For three generations to come, such record parties would be social events, but the nature of the event would change. By the 1950s, a party-goer would be younger and come with a “thumb full” of 45s, and the player would be set up in the garage where there was enough room to do and demonstrate all the latest dances.

What made the party a good one was if the participants brought with them enough of the latest releases. The idea of sitting and listening to a recording, then discussing it, continued through the 1960s and 1970s, the hippie generation and the concept album.