Columbia Records

Then the public began to buy phonographs. In general these playback applications required a ready supply of pre-recorded material and in 1890 the D.C. operation began to sell pre-recorded cylinders under the Columbia label (thus the oldest record label in the world came into existence).

The survival of this one company was due to its astute pursuit of alternate markets and because it began to sell recordings on the Columbia label (named after the District Of Columbia).

By 1891, Columbia had 200 titles in its catalog and was the largest record company in the world. But a major obstacle in commercializing pre-recorded material was the difficulty in duplicating a title. To produce a batch of 200 recordings of a march, it had to be played 20 times in front of a battery of 10 recording horns. For the phonograph to prosper as public entertainment, the production process and duplication had to be simplified and cost effective.

In 1900, the company had opened a London office and by then was selling both Edison cylinders and Berliner disks. Due to financial problems during World War I, the U.S. operation was forced to sell its British subsidiary to the local manager Louis Sterling. A year later, U.S. Columbia also failed and the British operation bought it from receivers to get access to the recently developed electric cutting system that was only available to U.S. companies.

The company was reorganized in 1925 and went international, operating under different names in different countries. In the U.S. it was known as the General Phonograph Company Inc. The company invested in broadcasting by taking over United Independent Broadcasters and renamed the U.S. operation the Columbia Phonograph Broadcasting Co. During the depression in the 1930s, the company again had financial woes, and in particular, the performance of the U.S. record operation was poor (sales were 6 percent of 1927 levels).

The broadcast network had potential but was equally unprofitable, so bad sales and the likelihood that it was in violation of antitrust laws due to this 50 percent interest in the Victor Talking Machine Company in the U.S. caused the company to divest its U.S. interest in Columbia. Meanwhile, Columbia U.K. was merged with HMV (the U.K. operation of the Victor Talking Machine Company) in 1931, and the company was renamed the Electrical and Music Industry (EMI). The U.S. radio network continued as the Columbia Broadcasting System and became profitable during the next decade.

The U.S. Columbia Records was sold to Grigsby-Grunow, a manufacturer of refrigerators and radios. This company went bankrupt in 1934, and Columbia was sold to the Brunswick label. The American Record Company (ARC) had been formed in 1929 through the merger of three small labels, Oriole and Perfect, Romeo, and Banner.

ARC acquired the Brunswick label (started in 1916) in 1931 and changed the name of the entire company to Brunswick Record Corporation, of which it was at the time of the Columbia acquisition. CBS bought Brunswick in 1938. CBS deactivated the Brunswick label and reactivated the Columbia label, later selling Brunswick to Decca in 1942.

Outside the U.S., the Columbia label would remain EMI’s flagship pop label until the early 1950s when CBS pulled out of its overseas arrangement with EMI. We’ll return to the EMI, HMV and Victor Talking Machine Company connections subsequently.

Berliner’s Gramophone

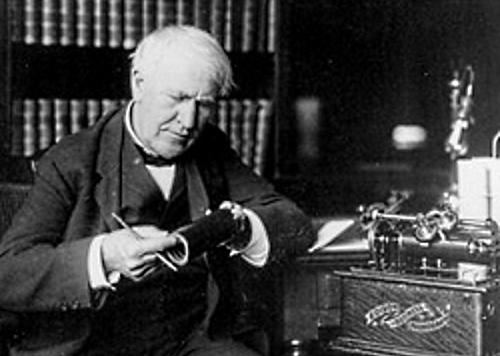

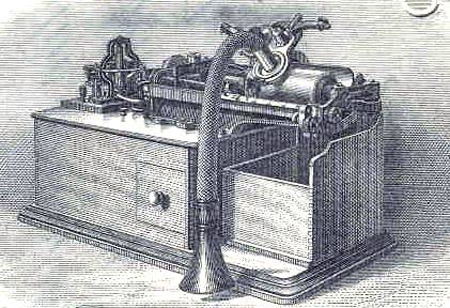

A German inventor living in the U.S. solved the duplication problems associated with the cylindrical shape of the Edison phonograph. Emil Berliner would have been aware of Scott’s invention and it is widely accepted that he knew of Cros’s patent. Berliner’s approach used a round flat plate as a recording surface.

This approach made duplication significantly easier whereby records could be pressed much like waffles and not very different from the way records were made until the CD came along (in fact CDs are also a pressed medium).

In 1895, Berliner formed the Berliner Gramophone Company and began to sell a hand driven player. An associate of Berliner’s, Eldridge Johnson, incorporated a wind-up spring motor and the modern gramophone was complete. The two of them started the Victor Talking Machine Company in 1901 for the purposes of manufacturing gramophones and producing records.

Berliner’s foreign rights agent travelled to London in May 1898 in order to raise enough funds to establish a recording and pressing facility. To pay for an expensive patent war with Columbia, Berliner sold his patent rights in Britain and Europe to a group of English investors called the Gramophone Company.

The initial catalog of records was pressed by Berliner’s brother in a factory set up in Hanover, Germany. During World War I, the Hanover operation became Deutshe Grammophon, which would evolve into Polygram. In 1902, Columbia and Victor pooled their patents and put aside a legal case that was pending. This freed them both to put all their efforts into promoting their products. Between 1902 and 1906, The Victor Company, in order to stimulate record sales, gave away models of the Type P Premium Player when a customer purchased several records at once.

Columbia began selling disks in the U.S. in 1901, but Victor quickly became the dominant label in America. In 1902, Gramophone manufactured the first 78RPM record and in 1907 a double-sided disk was issued. In 1912, Edison introduced the diamond tipped stylus which further improved the reproduction quality. By 1917, both Columbia and Victor were emphasizing the ability of their machines to supplant a dance orchestra at the most elegant and stylish affairs.

In 1900, the Gramophone Company bought the rights to Francis Barraud’s painting of his dog Nipper sitting in front of a phonograph. The artist was paid £50 for the painting and £50 for the copyright providing he changed the phonograph to a gramophone. Barraud painted a gramophone right over the original. The name of the painting was “His Master’s Voice” which became a trade mark and label (HMV) for the Gramophone Company.

When Berliner visited London he asked to use the image as a trademark in the U.S. Berliner, Victor, then RCA all used Nipper. In Egypt, India and Moslem countries it was not used at that time by HMV because dogs were considered unclean. In India, a listening cobra was substituted for the dog on those records with Indian artists. In Italy it was never used because there, a bad singer was said to sound like a dog. Victor also used the logo for releases on its Japanese subsidiary which was sold to Japanese interests before World War II.

HMV and The Victor Talking Machine Company maintained an ownership in each other for 50 years. Johnson sold his interests to bankers Seligman and Sprayer in 1926. During the depression record sales dropped through the floor. The Camden New Jersey pressing plant was converted to making radios. Victor dropped most of its artists though many later appeared back on the label through the HMV connection.

In 1929, the Radio Corporation of America bought Victor from the lawyers. RCA had no intention of continuing the record operation but wanted the company for the radio manufacturing facilities. When ASCAP began to claim that the radio industry should pay royalties for air play which eventuated in the first arrangement with the National Association of Broadcasters (1932), RCA realized that the Victor catalog was a gold mine and decided to continue the label using the pressing plants that it had acquired along with the radio plant. The RCA-Victor label was begun.