A while back, one of the neighbors in the industrial complex where I keep my shop came over to say hello while I was in the middle of doing some PM (preventative maintenance) on cables.

As I sat at a bench surrounded by piles of microphone and loudspeaker lines, he asked why I was spending so much time on “stupid cords.” I replied, simply, that without the stupid cords, the rest of my equipment is worthless. A system is only as good as its cables, interconnects, snakes, and networks—period. Fortunately, we have a wide variety of analog and digital options to choose from, and it’s getting better on a constant basis.

Digital audio transport technology (a.k.a., digital snakes and networks) have taken pro audio by storm in the last few years, pushed at least in part by the proliferation of digital consoles, with virtually every manufacturer offering some way to move audio over Cat-5/6, coax, and fiber optic cabling. While digital networking certainly offers a lot of advantages and flexibility, it hasn’t pushed analog completely out of the picture—and in my opinion, at least, I don’t think it will, at least in the foreseeable future.

One reason is personal preference, another is the sheer amount of cabling that will have to be replaced, and yet another big one is that digital systems need A-D and D-A conversion at each end of the cable (or fiber), which increases cost, and this is particularly dramatic for smaller systems that only run a few channels of audio. As technologies improve and prices come down, I’m sure we’ll see even more digital, even on the smallest of shows, but there’s still the issue of preference.

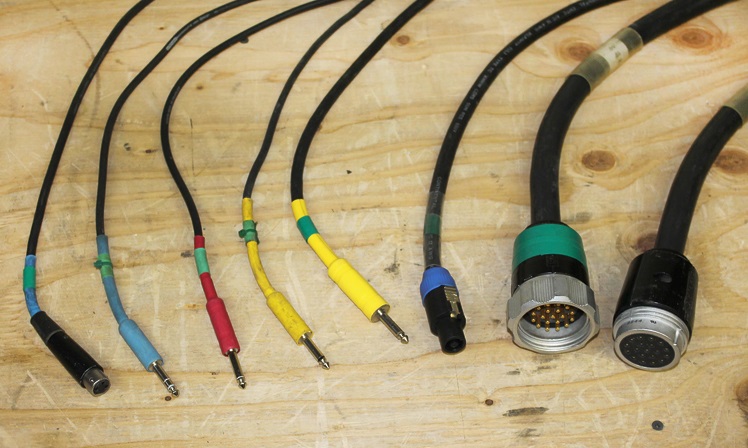

That said, let’s take a look at the various cables, connectors, and audio transport used in production audio systems.

Here To There

The first cable in the signal chain is usually the humble XLR cable sporting 3-conductor connectors at each end. These cables connect low-impedance microphones and direct boxes to consoles, as well as send line level signals around to various gear.

They operate on the balanced principle and contain two insulated conductors that are twisted together inside a shield under the outer jacket. The two signal conductors carry the same signal but in opposite polarity from each other. The receiving device subtracts the two signals from each other, which reinforces the original signal while cancelling any noise picked up along the way.

The reason the inner conductors are twisted is that it allows external noise to be introduced to both signal conductors equally (or as equally as possible) and improves the common-mode rejection ratio. Some cables use four inner conductors (two pairs of two) that offer better rejection from outside electromagnetic interference like transformers and fluorescent lighting ballasts.

The conducting shield that wraps around the inner wires is used for the signal common and can be a spiral winding or a braided winding. Braided shields provide more surface area coverage and better rejection of radio frequency interference (RFI) than spiral wound shields.